Inside Hawaii’s only burn unit, doctors rushed to treat Maui victims

GO NAKAMURA / NEW YORK TIMES

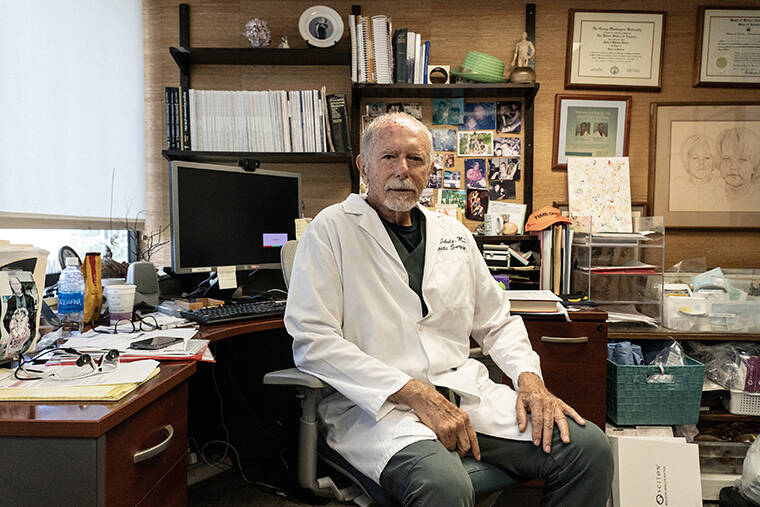

Dr. David C. Cho, a plastic surgeon who works in the burn unit at Straub Medical Center in Honolulu, Aug. 14. After wildfires in Maui, an island airlift brought some of the fire’s most severely wounded survivors to a Honolulu hospital unit created for just that kind of mass-casualty moment.

GO NAKAMURA / NEW YORK TIMES

Kimberly Webster, a registered nurse and the manager of the burn unit at Straub Medical Center in Honolulu, Aug. 14.

GO NAKAMURA / NEW YORK TIMES

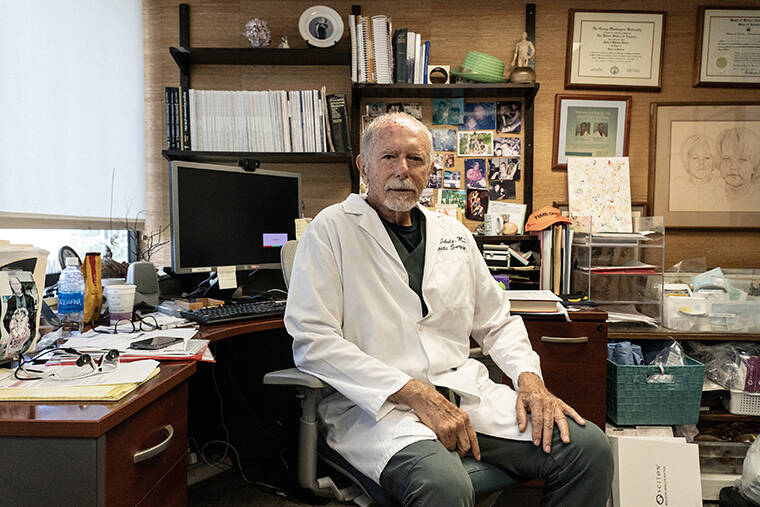

Dr. Robert W. Schulz, the medical director of the burn unit at Straub Medical Center in Honolulu, Aug. 14.

When Dr. David C. Cho’s phone rang in the middle of the night, it was an emergency room physician calling from Maui, two islands away, seeking help.

“In very plain and simple terms he said, ‘Lahaina is destroyed,’” recalled Cho, a plastic surgeon who works in the burn unit at Straub Medical Center in Honolulu. “And then it just went silent.”

Cho got out of bed, went to the hospital and waited.

“I just knew there was going to be a pipeline of patients,” he said.

As hurricane-fanned flames overwhelmed Maui last week and rescue crews worked frantically to reach the wounded, some survivors’ injuries proved too extensive for that island’s hospitals and needed the most intensive burn care available. Nine burn patients were flown nearly 100 miles to Honolulu and then driven by ambulance to Straub, whose burn unit is the only facility of its kind in Hawaii, and the only one in the North Pacific between California and Asia.

At the Honolulu hospital, doctors and nurses went to work trying to stabilize the crush of new arrivals, who ranged in age from young adults to seniors, and whose second- and third-degree burns in some cases covered up to 70% of their bodies.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

For the doctors, the nine arriving victims represented the largest influx of patients from a single incident in the burn unit’s history. As consumed as the medical workers were with the extraordinary needs of these patients, another question lingered: Might more be flown in soon — more people who could be saved?

Back on Maui, what would become the country’s deadliest wildfire in more than a century was still not contained, and newly homeless evacuees from Lahaina, an oceanside town that was once the capital of the Hawaiian kingdom, were pouring into shelters. Inside the operating rooms and yellow-walled hallways of the burn unit in downtown Honolulu, there was no time to learn those details.

“As a surgeon, you have to just take it one step at a time and take care of the patient in front of you,” Cho said in an interview inside the hospital this week. “In fact, I probably was one of the least-informed persons on the island in that first 36 hours because I didn’t have time to know what was on CNN.”

Hospital officials declined to provide specifics on the conditions of patients from the wildfire, citing privacy concerns.

But the disaster underscored the reason the unit was created, said Dr. Robert W. Schulz, a plastic surgeon who co-founded the unit with Dr. James Penoff.

Until the 1980s, there was no burn treatment facility in Hawaii, which meant doctors had to track down airplanes to transport people to the mainland to receive specialized care. Too often, patients died before they got there. And even when they did make it to California, they would sometimes spend long hospital stints away from their families, undergoing painful treatments.

Schulz, the unit’s medical director, was among those treating the Maui patients in recent days. He described working to make sure victims losing vast amounts of blood received enough fluid. He recounted long stretches in the operating room that started in the morning and lasted until 8 at night. And he cautioned that with many burn patients, the worst days of treatment are not the first ones.

“You come in, you’re articulate for about 12 hours, and then, you know, you’re now medicated so much that for the next three to four months you’re in continual surgery,” Schulz said, speaking generally about patients with extensive injuries.

Kimberly Webster, a registered nurse who is the manager of the burn unit and a critical care unit at Straub, said she had been following the weather early last week, aware that intense dryness and high winds from a hurricane off Hawaii’s coast had increased the fire danger. She said she had tracked those reports in the same way she might monitor the Fourth of July, when the proliferation of fireworks increases the possibility of severe burns. But there was no preemptive effort to add staff or clear rooms.

“You’re alert and you’re aware of that,” said Webster, “but you don’t start moving people when you don’t need to.”

That started to change on the evening of Aug. 8, as the first reports of destruction on Maui began to filter in. Early on, Webster said, there were indications that around 10 patients might need to be flown in. But much remained unclear.

Given Hawaii’s geography, the doctors and nurses at Straub are used to treating patients arriving by plane. The unit regularly takes in burn victims from other islands in Hawaii, from U.S. territories like Guam, from Pacific nations like Micronesia and from cargo ships at sea.

But those patients usually come one or two at a time. The volume of new arrivals from the wildfire and the speed with which they arrived became a singular event in the careers of the doctors and nurses.

As doctors at Straub spoke with their counterparts on Maui, in some cases reviewing photos or videos of wounds, they made decisions on which patients needed to be transferred. In some less severe cases, patients can receive care outside a formal burn unit. In other instances, a person’s burns might be so extensive, and their prognosis so poor, that focusing on their comfort is more appropriate than putting them through a flight.

“But it’s that big piece in the middle that you can provide a quality of life and a real benefit,” Schulz said. “They’re now treatable and you can save them and you have this facility that can do it for them that is not 2,000 miles away.”

Advances in treatment in recent decades, including the development of skin substitutes, have improved the long-term outlook for people who sustain massive burns. Still, hospital stays regularly last for months and involve painful daily treatments and repeated surgeries.

In many cases, surgeons must remove healthy skin and graft it onto parts of the body that burned. But after one graft, it takes time for skin to grow back to allow for another. And for patients with burns on 70% of their body, there is relatively little healthy skin left to graft from in the first place.

In between surgeries, nurses work to keep the wounds clean, properly bandaged and free from infection. In a small room with waterproof flooring and heated ceiling tiles in a corner of the burn unit, nurses in plastic gowns will methodically wash wounds, sometimes spending two hours with a single patient. The room is warmed to about 85 degrees, Webster said, a temperature that helps stave off hypothermia for patients without skin but that can leave medical providers drenched in sweat.

“It’s uncomfortable for the patients,” Webster said of the washing process, and “it can be uncomfortable for the nursing staff.”

In interviews, medical providers in the unit, many of whom are longtime Hawaii residents, said they found deep meaning in being able to help their state through the fire. But with the known death toll now at 99 and likely to increase, they lamented that they had not had the chance to save more people.

“It’s heartbreaking,” Cho said. “I wish there were more transfers coming in — that’s my real reflection.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times Opens in a new tab.

© 2023 The New York Times Company