Still shaping the industry

NEW YORK TIMES

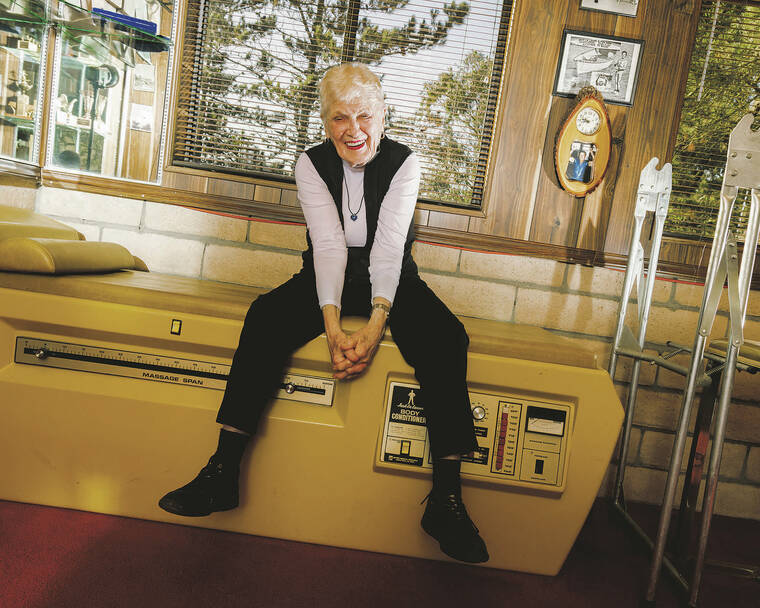

Elaine LaLanne, who revolutionized modern exercise alongside her husband, Jack, at home in Morro Bay, Calif. LaLanne said that her life has been built on the importance of positive thinking.

Elaine LaLanne’s morning exercises often begin before she’s even out of bed. Lying on top of the covers, she does two dozen jackknifes. At the bathroom sink, she does incline pushups. After she dresses and applies her makeup, she heads to her home gym, where she walks uphill on a treadmill for a few minutes and does lat pull-downs on a machine.

“Twenty minutes a day gets me on my way,” she said at her home on the central coast of California.

But her biggest daily feat of strength, she said, happens above her shoulders. At 97 years old, LaLanne reminds herself each morning, “You have to believe you can.” She said that belief had not only kept her physically active through injuries and emotional obstacles, it had also helped her to live the life of someone decades younger. “Everything starts in the mind,” she said.

LaLanne’s habit of speaking in aphorisms (“It’s not a problem, it’s an experience”; “You do the best you can with the equipment you have”) is a product of a lifetime of trying to inspire people to move more and better themselves. For nearly six decades, she was both wife and business partner to the television personality Jack LaLanne, who is widely considered the father of the modern fitness movement, and whose exercise show ran for 34 years, from 1951 to 1985.

“She was the guiding force behind Jack,” said Rick Hersh, Elaine LaLanne’s talent agent for more than 40 years.

While Jack was a natural showman — he rose to fame performing acrobatics on Santa Monica’s Muscle Beach in the 1930s — Elaine preferred to work behind the scenes, supporting him and managing their sprawling entertainment and entrepreneurial empire, which included not only a TV show but dozens of fitness gadgets, food products and supplements, as well as a gym chain with more than 100 locations nationwide.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

Since Jack’s death in 2011, however, Elaine (whom friends call LaLa) has quietly cultivated a following all her own. She still runs her family’s remaining business, BeFit Enterprises — which sells archival videos and memorabilia, and licenses the LaLanne name — from a ranch nestled among dusty hills and livestock.

She has published two books in the past four years and is developing both a documentary and a feature film with Mark Wahlberg, who has signed on to play Jack. And longtime fitness industry power players — 1990s home workout queen Denise Austin, Tae Bo guru Billy Blanks, bodybuilding legend Lou Ferrigno — seek her counsel on navigating life and business.

“She’s almost like a second mom to me,” Ferrigno said.

In July, at the annual conference of the Idea Health and Fitness Association, LaLanne walked the halls with a smile and a shiny new walker as a steady stream of toned, Lycra-clad fitness professionals stopped her for selfies. For more than a decade, she has presented the Jack LaLanne Award, an industry lifetime achievement prize given to fitness personalities promoting health and exercise in the media.

“A lot of our members come for her,” said Amy Thompson, the CEO of Idea. “We may have to change the name to the Elaine LaLanne Award.”

After all, in 1926, when LaLanne was born, few Americans made exercising a part of their daily lives, said Shelly McKenzie, an independent scholar and the author of “Getting Physical: The Rise of Fitness Culture in America.” Nearly a century later, LaLanne is a “testament to the efficacy of a lifelong exercise habit,” McKenzie said — and perhaps even more important, the power of choosing how you want older age to look and feel.

Raised in Minneapolis, LaLanne dreamed of a career in entertainment. In the mid-1940s, she went west to San Francisco, where she worked her way into the nascent medium of television, eventually becoming a producer and co-host of a live daily variety show, which was rare in an era when few women in the medium moved beyond secretarial roles. By the early 1950s, she had become a local celebrity, whom one reporter called “the sweetheart of San Francisco television.”

A divorced single mother with a demanding job, Elaine, then 27, smoked cigarettes, ate candy bars for lunch and, like most Americans of the time, didn’t devote much thought to exercise and nutrition.

Then one day in 1951, the press agent for a local bodybuilder and gym owner called the studio and said her client could do pushups on air for an entire show. Sure enough, Jack LaLanne pulled it off, lifting and lowering his 5-foot-6-inch frame through a full 90-minute program while the hosts carried on as usual.

Soon after they met, Jack walked over to Elaine’s desk at the studio and chided her for eating a doughnut and smoking. “She blew him off, literally, taking a gratuitous bite of her doughnut and puffing cigarette smoke in his face,” fitness historian Ben Pollack wrote in 2018.

But in time, she fell not only for him, but for his beliefs about eating whole foods and exercising — which he adapted from the early 20th-century lifestyle celebrity Paul Bragg, and which he credited for transforming him from a sickly youth to a bodybuilder. It got her thinking, “I don’t want to be old when I’m old.”

With Elaine’s television background and Jack’s charisma, the LaLanne star rose. Jack’s appearance on Elaine’s show eventually led to his own live show on the same network and then “The Jack LaLanne Show,” in Los Angeles, which became the first national series devoted to diet and exercise. As Jack was getting settled in Hollywood, Elaine would host his Bay Area show and give lectures across the state about healthy living.

She also began running the business details of product development and licensing deals that presaged the modern personality- driven fitness market — including a Jack LaLanne bathroom scale, a “Glamour Stretcher” resistance band and vitamins.

But she was most known for her appearances in front of the camera as a co-host.

“I was always looking for role models,” said Jan Todd, a pioneer in women’s powerlifting and interim chair of the department of kinesiology at the University of Texas at Austin. “I grew up before Title IX passed. Mom didn’t go to a gym.” Todd found inspiration in Elaine LaLanne, who, with her blond bob and cheerful disposition, made building muscle seem acceptable for women.

In retrospect, not all the LaLannes’ messages promoted health. To watch early episodes is to watch contemporary diet culture being born, promoting a thin body ideal and presenting fat as a problem to be conquered, McKenzie said. They coined and popularized catchphrases including “10 seconds on the lips and a lifetime on the hips.”

Elaine LaLanne stands by these messages, saying they were giving viewers tools and confidence to achieve their goal. But she acknowledged that “it’s better” now that there is a diversity of body sizes on TV.

With her ever-present smile and her fondness for catchphrases, LaLanne’s positivity could easily be mistaken for naivete. But her sunny outlook is hard won, most profoundly as a result of May 24, 1973, when her 21-year-old daughter from her first marriage, Janet, died in a car accident. The night she learned her child had been killed, she said, she was faced with a choice: Fall apart or push through.

She thought to herself, “Janet, if she can see you up there, she would never want to see me cry,” LaLanne said, choosing her words carefully. “I mean, I can’t — she’s gone, I can’t do anything about it. Can’t bring her back.”

The woman who had preached the gospel of changing your life knew this was one thing she could never change. She managed her grief the way she approached everything else — by hurtling forward, she said, and by training her brain, like a muscle, to focus not on her loss but on the joy her daughter had brought her when she was alive.

The LaLannes’ greatest legacy, Todd said, may be “showing us the value of exercise in relation to aging.”

As he got older, Jack would perform media stunts on his birthday. At 70, he towed a flotilla of 70 rowboats filled with 70 people during a mile-long swim. Elaine began writing books about moving through middle age, with titles like “Fitness After 50” and “Dynastride!”

While people who worked closely with the LaLannes say that she was the backbone of the empire, Elaine herself sidesteps credit for her role in building it. When nudged to highlight her achievements, she quickly changes the subject to something else — usually Jack — or falls back into her signature aphorisms (“It takes two to tango,” “A one-man band is good, but more in the band makes it better”). Even her emails show up as “Jack LaLanne.”

Elaine LaLanne said she had slowed down since turning 92. She has also fallen several times over the past decade. But the physical strength she gained at the gym helped her get back on her feet, she said.

Along with her daily exercises, LaLanne devotes time to stretching and hanging from a pullup bar, letting her body hang loose like a rag doll. She uses the same workout equipment that she and Jack used for most of their lives, including weight machines Jack designed in the 1930s and a treadmill the couple purchased in the early 1970s.

“You have to move,” she said. “If you don’t move, you become immovable.”

© 2023 The New York Times Company