Nobel Prize awarded to COVID vaccine pioneers

ASSOCIATED PRESS

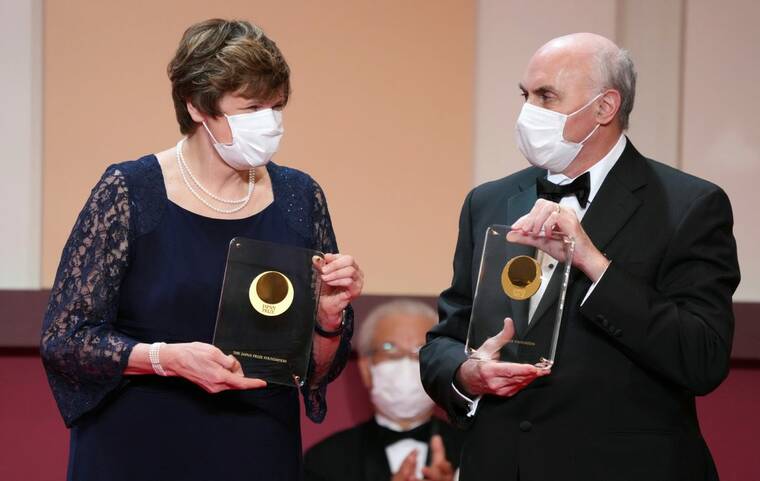

Japan Prize 2022 laureates Hungarian-American biochemist Katalin Kariko, left, and American physician-scientist Drew Weissman, right, pose with their trophies during the Japan Prize presentation ceremony, in April 2022, in Tokyo. The Nobel Prize in medicine, awarded to Katalin Karikó Drew Weissman for enabling the development of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines, was announced today.

Katalin Karikó and Dr. Drew Weissman, who together identified a chemical tweak to messenger RNA, were awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine today. Their work enabled potent COVID-19 vaccines to be made in less than a year, averting tens of millions of deaths and helping the world recover from the worst pandemic in a century.

The approach to mRNA the two researchers developed has been used in COVID shots that have since been administered billions of times globally and has transformed vaccine technology, laying the foundation for inoculations that may one day protect against a number of deadly diseases such as cancer.

The slow and methodical research that made the COVID shots possible has now run up against a powerful anti-vaccine movement, especially in the United States. Skeptics have seized in part on the vaccines’ rapid development — among the most impressive feats of modern medical science — to undermine the public’s trust in them.

But the breakthroughs behind the shots unfolded little by little over decades, including at the University of Pennsylvania, where Weissman runs a lab.

Weissman said he found out about the prize at 4 a.m. when Karikó texted him, asking if he had heard from Thomas yet. “No. Who’s Thomas?,” he replied. Kariko told him that Thomas was from the Nobel committee. He was looking for Weissman’s phone number.

Karikó, the 13th woman to win the prize, languished for many long years without funding or a permanent academic position, keeping her research afloat only by latching onto more senior scientists at the University of Pennsylvania who let her work with them. Unable to get a grant, she said she was told she was “not faculty quality” and was forced to retire from the university a decade ago. She remains only an adjunct professor there while she pursues plans to start a company with her daughter, Susan Francia, who has an MBA and was a two-time Olympic gold medalist in rowing.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

The mRNA work was especially frustrating, she said, because it was met with indifference and a lack of funds. She said she was motivated by more than not being called a quitter; as the work progressed, she saw small signs that her project could lead to better vaccines. “You don’t persevere and repeat and repeat just to say, ‘I am not giving up,’” she said.

She and Weissman had their first chance meeting over a copy machine at the University of Pennsylvania in 1998.

Karikó, the daughter of a butcher, had come to the United States from Hungary two decades earlier when her research program there ran out of money. She was preoccupied by mRNA, which provides instructions to cells to make proteins. Defying the decades-old orthodoxy that mRNA was clinically unusable, she believed that it would spur medical innovations.

At the time, Weissman was desperate for new approaches to a vaccine against HIV, which had long proved impossible to defend against. A physician and virologist who had tried and failed for years to develop a treatment for AIDS, he wondered if he and Karikó could team up to make an HIV vaccine.

It was a fringe idea that, when they began their research, seemed unlikely to work. The mRNA was delicate, so much so that when it was introduced to cells, the cells instantly destroyed it. Grant reviewers were not impressed. Weissman’s lab instead relied on seed money that the university gives new faculty members to get started.

“We saw the potential and we weren’t willing to give up,” Weissman said.

For years, Weissman and Karikó were flummoxed. Mice injected with mRNA became lethargic. Countless experiments failed. They wandered down one dead end after another. Their problem was that the immune system interprets mRNA as an invading pathogen and attacks it, sickening the animals while destroying the mRNA.

But eventually, the scientists discovered that cells protect their own mRNA with a specific chemical modification. So they tried making the same change to mRNA synthesized in the lab before injecting it into cells. It worked: The mRNA was taken up by cells without provoking an immune response.

The discovery “fundamentally changed our understanding of how mRNA interacts with our immune system,” the panel that awarded the prize said, adding that the work “contributed to the unprecedented rate of vaccine development during one of the greatest threats to human health in modern times.”

At first, other scientists were largely uninterested in taking up that new approach to vaccination. Their paper, published in 2005, was rejected by the journals Nature and Science, Weissman said. The study was eventually accepted by a niche publication called Immunity.

But two biotech companies soon took notice: Moderna, in the United States, and BioNTech, in Germany, where Karikó eventually became a senior vice president. The companies studied the use of mRNA vaccines for flu, cytomegalovirus and other illnesses. None moved out of clinical trials for years.

Then the coronavirus emerged.

Almost instantly, Karikó and Weissman’s work came together with several strands of disparate research to put vaccine-makers ahead of the game in developing shots. That included research done in Canada that allowed fragile mRNA molecules to be safely delivered to human cells, and studies in the United States that pointed the way toward stabilizing the spike protein that coronaviruses used to invade cells.

By late 2020, less than a year into a pandemic that would eventually kill at least 7 million people globally, regulators had authorized strikingly effective vaccines made by Moderna and by BioNTech, which partnered with Pfizer to produce its vaccine. Both used the modification Karikó and Weissman discovered.

About 400 million doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine and 250 million doses of the Moderna vaccine have been administered in the United States. Hundreds of millions more have been given around the world. The use of mRNA has enabled both vaccines to be updated against new variants.

Karikó referred in an interview published by the University of Pennsylvania today to her many years of clinging to the fringes of academia. In the interview, Karikó said that every October, her mother used to tell her, “I will listen to the radio that maybe you will get the Nobel Prize.” Karikó said she would answer: “Mum, you know, I never even get a grant.”

Karikó is the 13th woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine since 1901, and the first since 2015. Women represent a small fraction of the total of 227 people who have been awarded the prize, a reflection of how women are still largely underrepresented in the field of science and scientific awards, including the Nobel Prizes.

Vaccines using mRNA technology are now being developed against a number of diseases, including influenza, malaria and HIV, which remains difficult to inoculate against. Personalized cancer vaccines have also showed promise. They use mRNA tailored to an individual patient’s tumor to teach the person’s immune system to attack proteins on the tumor.

Karikó and Weissman’s discovery, scientists said, remained critical in allowing mRNA vaccines to escape destruction by patients’ immune systems and to trigger the efficient production of vaccine proteins.

“What is now recognized as a transformative technology required dedicated scientists to carry out fundamental research over many years to reach the position it was in 2020 when its rapid deployment as a vaccine technology was made possible by global collaboration,” said Brian Ferguson, an immunologist at the University of Cambridge. “The work of Katalin Karikó and Drew Weissman in the years prior to 2020 made this possible, and they richly deserve this recognition.”

Who won the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 2022?

The prize went to Svante Pāābo, a Swedish scientist who produced a complete Neanderthal genome and helped create the field of ancient DNA studies.

When will the other Nobel Prizes be announced?

The prize for physiology or medicine is the first of six Nobel Prizes that will be awarded this year. Each award recognizes groundbreaking contributions by an individual or organization in a specific field.

— The Nobel Prize in physics will be awarded Tuesday by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm. Last year, John Clauser, Alain Aspect and Anton Zeilinger each won for independent works exploring quantum weirdness.

— The Nobel Prize in chemistry will be awarded Wednesday by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm. Last year, Carolyn R. Bertozzi, Morten Meldal and K. Barry Sharpless shared the prizes for work on “click chemistry.”

— The Nobel Prize in literature will be awarded Thursday by the Swedish Academy in Stockholm. Last year, Annie Ernaux earned the prize for work that dissected the most humiliating, private and scandalous moments from her past with almost clinical precision.

— The Nobel Peace Prize will be awarded on Friday by the Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo. Last year, the prize was shared by Memorial, a Russian organization; the Center for Civil Liberties in Ukraine; and Ales Bialiatski, a jailed Belarusian activist.

— Next week, the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences will be awarded today by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm. Last year, Ben Bernanke, Douglas W. Diamond and Philip H. Dybvig shared the prize for work that helped to reshape how the world understands the relationship between banks and financial crises.

All of the prize announcements will be streamed live by the Nobel Prize organization.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2023 The New York Times Company