Nearly 100 years ago Kilia Purdy-Avelino’s great- grandparents moved into the Hoolehua homestead on Molokai, one of the first homestead communities established under the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act.

She recently found a 1925 newspaper article penned by her great-grandmother Kalei Lindsey Purdy, who wrote of her homestead, “Today, I am so happy. Here I am on this land, and I am seeing the trust of all that was said about this blessed land, a place of milk and honey.”

Purdy-Avelino, who still lives on the Hoolehua homestead and farms the land with her family, said she finds it refreshing that her great-grandmother “saw the beauty, blessings and gifts of the land despite the challenges. Had it not been for (the first homesteaders’ success), we wouldn’t have homesteads today.”

One hundred years ago the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, which set aside about 203,000 acres of former crown and government lands in the Hawaiian kingdom for homesteads, was signed into law by President Warren Harding. On Friday, its centennial anniversary, community members, officials and legislators marked the occasion with mixed reactions. Many honor the legacy of Prince Jonah Kuhio Kalaniana‘ole, the act’s champion, and his advocacy for Native Hawaiians. But at the same time, others feel disappointed and saddened over the thousands of Hawaiians who still wait for homestead lots and the many who have died in the process.

“It’s bittersweet. It’s like sweet-and-sour pork or a delicious stew with bone shards in it,” said Robin Danner, chairwoman of the Soverign Council of Hawaiian Homestead Associations, the largest statewide organization representing all Hawaiians eligible for homesteads. “It’s about honoring a man with a vision and also reflecting on why that vision has not come to pass. The centennial is a time for sobering reflection.”

Regarded as a pivotal moment for Native Hawaiians, the law was a culmination of years of work by Prince Kuhio, known as the Citizen Prince, and many community advocates. In writing to the U.S. Senate to encourage passage of the homestead bill, Prince Kuhio, who served as a nonvoting delegate to Congress, said, “After extensive investigation and survey on the part of various organizations organized to rehabilitate the Hawaiian race, it was found that the only method in which to rehabilitate the race was to place them back upon the soil.”

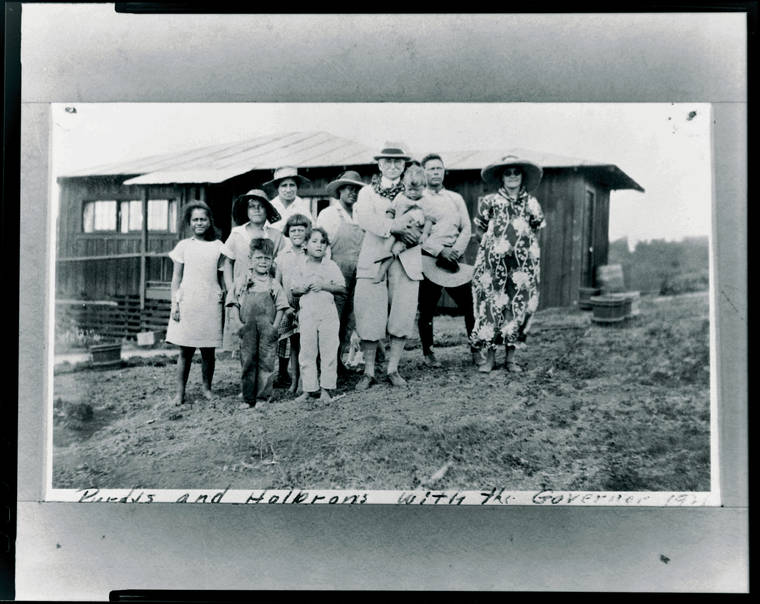

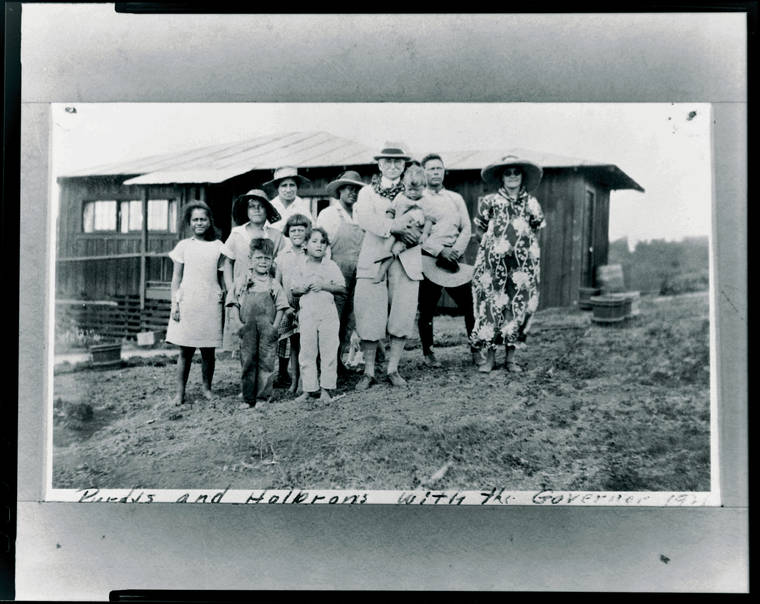

On July 9, 1921, the bill became law, creating a system that set aside land for Hawaiians with a blood quantum of at least 50%. Parcels would be leased for 99 years at $1 annually. A year later the first homestead family moved into the Kalanianaole Colony in Kalamaula, Molokai, just six months after Prince Kuhio died. After six years the program was deemed a success, and the act was fully instituted in March 1928.

Many years later as a condition of statehood, the act was adopted as a provision of the Hawaii Constitution on March 18, 1959. It also established the state Department of Hawaiian Home Lands, tasked with overseeing the act and seeing Prince Kuhio’s vision through. At the time, about 1,700 Hawaiians had received homestead lots with 2,500 on the wait list.

“To this day (the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act) remains the most significant piece of legislation for the advancement of Native Hawaiians,” said U.S. Rep. Kai Kahele at a ceremony Friday in Washington, D.C. Officials also gathered at an event in Kapolei, where Gov. David Ige presented a proclamation commemorating the centennial anniversary. “We would not be here without the intentional foresight of one man. As a nonvoting delegate to the then-territory of Hawaii, his ability to pass this landmark legislation proved his talent as a skilled diplomat and remarkable leader.”

In the years since passage of the act, DHHL, state and federal officials have come under fire for what advocates say is mismanagement of the trust and a lack of leadership, accountability and reform in building enough lots to shorten the 28,792-person wait list.

In 1999 about 2,700 kupuna filed a class-action lawsuit against the state, saying officials mismanaged the land trust. The Hawaii Supreme Court ruled in the plaintiffs’ favor last year and allowed the lawsuit to proceed to the next stage in calculating damages for those who have spent decades awaiting homestead lots.

Additionally, a Honolulu Star- Advertiser investigation in collaboration with nonprofit ProPublica found that after waiting sometimes for decades, many of the beneficiaries who are offered homestead lots find they cannot afford to finance a home. Although leases under the program are virtually free, applicants have to build their own homes or purchase one from a developer. The Star-Advertiser and ProPublica also found that thousands of acres of land no longer needed for government or military use that should have been recovered for Native Hawaiians were instead offered to private buyers.

“I’m not happy. It really gives people time to think,” said Mike Kahikina, chairman of the Association of Hawaiians for Homestead Lands, a statewide nonprofit representing those on the wait list. “One hundred years now, we still get people dying on the wait list. I’m mourning the 100 years for the invisible people.”

Hawaiian Homes Commission Chairman and DHHL Director William Aila Jr. pointed to the more than 4,000 lots built over the past 25 years, along with the 9,950 total homestead leases with nearly 200 applicants nearing completion as a sign of progress.

“Without the program there would be a lot less Native Hawaiians. There would be a lot less Native Hawaiian culture,” Aila said. “We haven’t been as successful as many folks would envision, but it’s not for a lack of trying. It is mainly a resource problem.”

Others point to initiatives intended to increase DHHL’s capacity, including new laws that allow for subsistence agricultural lots and rentals on homestead lands. In the past four fiscal years, the state Legislature has allocated $50,000 in capital improvements funding for both two-year periods. Over the next two fiscal years, legislators allotted a total of $78,000 in capitol improvements funding, the largest of its kind in the program’s history.

“There have been a lot of movements and developments that I think are very promising and exciting for DHHL,” said state Sen. Maile Shimabukuro, chairwoman of the Senate Committee on Hawaiian Affairs. “The Legislature has given DHHL historically high amounts of funding in the last couple of sessions, which has been long overdue.”

State Sen. Jarrett Keohokalole and state Rep. Daniel Holt, co-chairmen of the Native Hawaiian Caucus, expressed similar sentiments.

“We have a duty and responsibility to see (Prince Kuhio’s vision) through and make his dream a reality,” Holt said. “We’re trying to take practical steps to make a plan and make it come to life. It’s important for us to ensure that the money is spent efficiently so we can keep the funding at this level.”

Keohokalole, who also serves as vice chairman of the Senate Committee on Hawaiian Affairs, added that at the time of the act’s signing, “there were assumptions in many circles that the Hawaiian race was going to die out. The fact that we still have so much of our culture and the community exists the way that it does can be attributed to those early efforts. It’s a reminder that there’s a lot more that needs to be done to fulfill the vision of Prince Kuhio and to provide for the beneficiaries of the trust.”

But several advocates say it’s not enough. Danner, whose organization represents all beneficiaries, said money is not the issue. She said the problem is the mismanagement of the land trust by the state and a lack of oversight and accountability by legislators. Her group wants to be part of the solution, she said, and it has sent officials a list of suggested policy changes, such as requiring that five of the nine Hawaiian Homes commissioners be beneficiaries still on the wait list and establishing a statewide interagency council for department heads to discuss ways to advance the act.

“I know there is a human toll for those missteps. We’re not angry. We’re heartbroken,” Danner said. “We’re definitely not ‘woe is me.’ We are part of this democracy, too. We are excited to share solutions.”

While views differ on how the trust has been managed, many agree that the centennial honors Prince Kuhio’s legacy and the landmark legislation he championed.

“It’s a Bible for the beneficiaries,” said Hawaiian Homes Commissioner Patty Kahanamoku-Teruya, who lives on the Nanakuli homestead. “Prince Kuhio was a powerful man with many legacies. ‘Give my people land.’ Those are his words and I feel the same way. This is an ongoing thing that we tackle, and it’s not an easy thing to do. We paina (gather) with our beneficiaries and bring awareness of the act.”

—

History of the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act

>> March 1903: Prince Jonah Kuhio Kalaniana‘ole begins serving as a nonvoting delegate to Congress.

>> April 1919: Homestead bill passed by the Hawaii Territorial Legislature.

>> December 1920: Bill passed by the U.S. House of Representatives.

>> June 1921: Bill passed by the U.S. Senate.

>> July 9, 1921: President Warren Harding signs the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act into law.

>> Sept. 16, 1921: Hawaiian Homes Commission holds its first meeting.

>> Jan. 7, 1922: Prince Kuhio dies.

>> July 1922: The first homestead family moves into the Kalanianaole Colony in Kalamaula, Molokai.

>> March 1928: After its success the homestead act is fully instituted.

>> March 18, 1959: As a condition of statehood, the act is adopted as a provision of the Hawaii Constitution. The state Department of Hawaiian Home Lands is established and tasked with overseeing the act.

———

Jayna Omaye covers ethnic and cultural affairs and is a corps member with Report for America, a national service organization that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues and communities.