Review: School shooting turns teen into troubled star

COURTESY KILLER FILMS

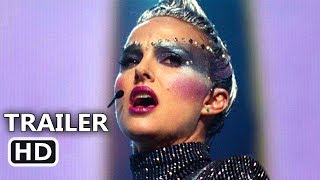

Natalie Portman plays a pop star, Celeste, in “Vox Lux.”

In “Vox Lux,” Natalie Portman gives the kind of aggressively big performance that teeters precariously, and at times excitingly, on the edge of vulgar indulgence. She plays Celeste, a drug-snorting, booze-chugging pop star, a banal narcissist who’s having a bad run personally and professionally, partly because she has sacrificed one for the other.

“Vox Lux” is an audacious story about a survivor who becomes a star, and a deeply satisfying, narratively ambitious jolt of a movie. Written and directed by Brady Corbet, it uses Celeste – an ordinary American girl who through a mass murder becomes extraordinary – as a means to explore contemporary spectacle.

Corbet is especially interested in celebrity and terrorism, which he positions (without much of a stretch) as powerful, reciprocal forces in the flux of life. Here, a terrorist attack in another country becomes a sound bite at an American pop star’s news conference and, like clockwork, fuels a scandal, a bleakly familiar transformation of news into a show.

The story proper opens with off-putting violence in 1999. The scene is a Staten Island high school class on the first day after a break, with a teacher (Maria Dizzia) welcoming her students. An armed student in black enters.

Teenage Celeste (Raffey Cassidy) tries to reason with the intruder, who guns down students, leaving a sickening, too-artful arrangement of the dead and wounded. Celeste survives and writes a eulogistic song with her sister (Stacy Martin) that becomes a sensation. She grows up to become a celebrity cliché that Portman, as the adult Celeste, takes on with outlandish verve.

The story unfolds in a series of discrete parts, some with self-conscious section titles that could seem merely pretentious if you miss the simmering, deep irony.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with top news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

Despite its spasms of violence, “Vox Lux” can be coolly funny, though you may be the only one laughing.

Its overarching tone is calibrated sardonicism, an approach that is most evident in the serene, once-upon-a-time narration from an offscreen Willem Dafoe. First heard over images resembling home movies, the voice-over – which introduces Celeste by placing her on the “losing side of Reaganomics” and refers to her “predetermined destination” – also tips that she isn’t the only creator of her story.

The dry grandiloquence of the narration makes Celeste a figure of pathos. In the early scenes, where she’s played by Cassidy, she’s a victim, delicate and fragile, particularly in the scenes in which Celeste undergoes physical therapy and, later, awkwardly tries out some dance moves. You’re drawn to Celeste, yet her ambition suggests there’s more to her, a greediness.

Portman enters in the second half and stays for the remainder. With her belted jeans and leather jacket, she brings to mind the mid-1980s Madonna (Lady Gaga, too), whose motorcycle babe in turn summoned up Monroe and Brando, a dizzying chain of pop-culture signification.

By this point in the story, Celeste has it all, has done it all, a lot of it questionably. Hovered over by her longtime manager (a perfect Jude Law), she has betrayed intimates, indulged in the usual vices and become a tabloid mainstay. Her luminescence has disappeared, leaving in its place a hard, shiny 21st-century brand.

The film has a fantastic score by Scott Walker that provides the familiar narrative assistance and editorializing, at times helping shift the tone from the intimate to the monumental, from the relaxed to the menacing.

In a brief, bravura sequence that bridges crucial moments in the young Celeste’s life, the music — its swirling, urgent strings and resonant, heavily punctuating drums — accompanies low-angle images of New York buildings. The music and upward-looking shots suggest the point of view of someone small but also looming, ominous power.

Portman’s performance puts an exclamation point on Celeste’s every gesture. Everything about the character is outsized, extreme, including an accent that sounds like it’s been lifted from a New York cabby in an old Hollywood comedy.

Celeste is by turns opaque and transparent; with her hair pulled off her face, her eyes darkly made-up (in an echo of the school shooter), she looks as if she has become her own mask. Much about her is different from when she was young, but when a second mass murder casts a shadow over Celeste’s life — and she quips about it — Corbet seems to be hewing to Marx’s dictum that history happens first as tragedy and then as farce.

“VOX LUX”

****

(R: 1:54)