Cities cut government contracts for immigrant detention as protests grow

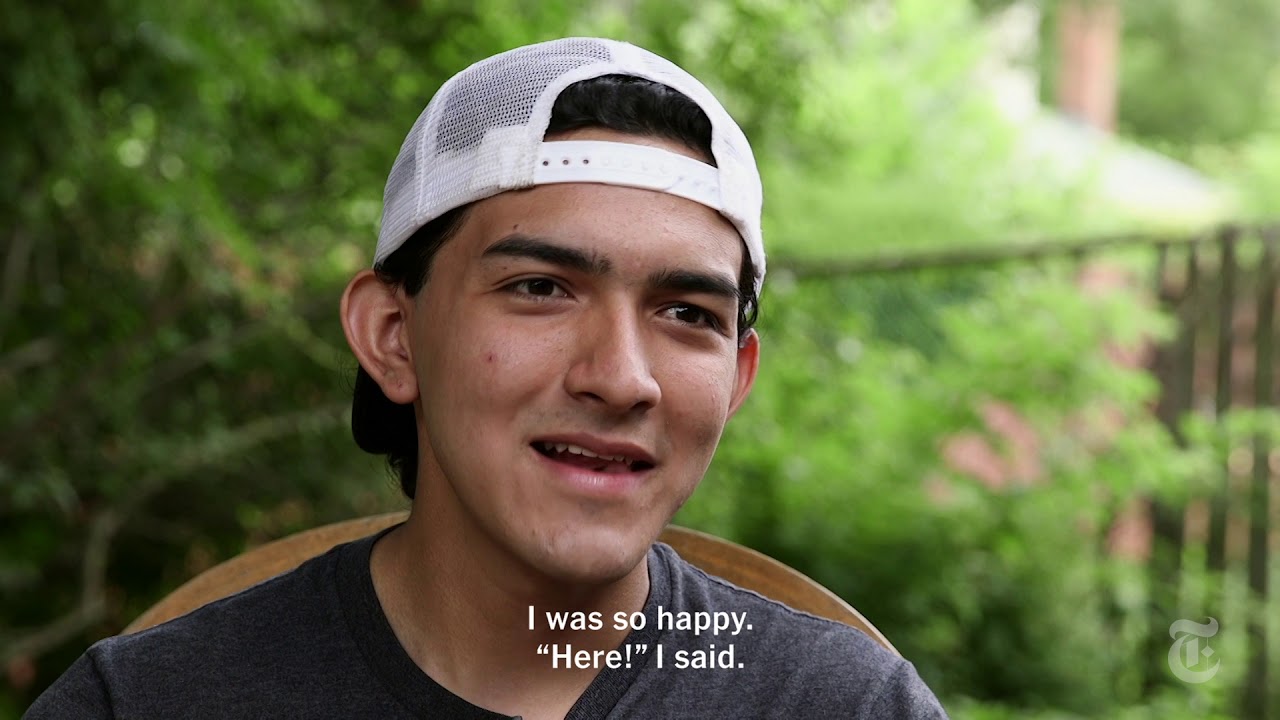

COURTESY NEW YORK TIMES (VIDEO SCREENSHOT)

For one teenager who fled violence in El Salvador on his own in 2014, the days he spent in a Texas border detention center were some of the worst of his life. He tells us what it was like.

EL PASO, Texas >> In Texas, officials near Austin terminated a contract with Immigration and Customs Enforcement to detain dozens of migrant mothers who had been arrested and separated from their children. In California, Sacramento County ended a multimillion-dollar deal with ICE to keep immigrants jailed while awaiting hearings.

The City Council of Springfield in western Oregon voted unanimously to end yet another contract with ICE for housing immigrants in the municipal jail. And in Alexandria, Virginia, authorities put an end to a deal allowing ICE to house immigrant children in a juvenile detention center.

Local governments around the United States are starting to sever lucrative ties with federal immigration entities amid growing discomfort with the Trump administration’s immigration policies. Fueled largely by alarm over the separation of migrant children from their parents, the cancellations suggest an attempt to disengage from federal policies seen as harmful to immigrant families — even when those policies could be pouring millions of dollars into local government budgets.

“It just felt inherently unjust for Sacramento to make money from dealing with ICE,” said Phil Serna, a Sacramento County supervisor who joined two colleagues in canceling the contract. “For me, it came down to an administration that is extremely hostile to immigrants. I didn’t feel we should be part of that.”

The local debates over what to do with ICE facilities come at a time when federal immigration policies are disrupting local politics. Insurgent Democratic candidates on the left who are winning primaries, such as Deb Haaland in New Mexico and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in New York, have made defunding or abolishing ICE a central feature of their campaign platforms.

But even before the uproar this month over separations of migrant families, claims of overreach and inhumane treatment by ICE agents, including targeting immigrants outside churches, schools and courthouses, were flaring tempers in communities around the country.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

“Dealing with ICE became distracting from the day-to-day operations of running our county,” said Terry Cook, a commissioner in Williamson County in Texas, a relatively conservative part of the Austin metropolitan area where Dell Computer employs thousands of people.

Cook was among the commissioners who voted 4-1 this week to end the county’s contract with ICE by 2019, an agreement under which nearly 40 mothers separated from their children have been held in the T. Don Hutto Residential Center. The facility is managed by CoreCivic, a private prison operator, through an intergovernment agreement with the county.

“The federal government made their bed with its policies, so let them sleep in it,” said Cook, emphasizing that efforts to end the contract had started to gain momentum about four months ago, well before the migrant family separations made national headlines. “We did not need to be in the middle of this.”

In another sign of public concern over immigration policies, even some private companies and nonprofits are balking at potentially lucrative deals with federal immigration agencies. Two Texas entities, APTIM and BCFS, declined this month to participate in a proposed no-bid contract worth as much as $1 billion to expand a tent camp for migrant children, according to a report by Texas Monthly.

In some parts of the country, the discussions over ICE contracts seem to be widening political fissures.

Residents of Evanston, a town of 12,000 in southwest Wyoming, have been fiercely debating for weeks a proposal by the private prison operator Management Training Corp. to build an ICE detention center near the community. The project could create as many as 150 jobs in a region with a relatively weak economy.

Some in Evanston compare the plan to the concentration camps built in Wyoming for Japanese-Americans during World War II. But accusations of racism and xenophobia leveled against supporters of the project have produced angry rebuttals. Jim Hissong, director of family services for Uinta County, which encompasses Evanston, said opponents of the facility were “using the same kind of divisive rhetoric that Trump uses.”

“I don’t like being called immoral and a racist,” said Hissong, who described himself as a “Reagan Republican” who dislikes the Trump administration. “I just believe that the federal government has an obligation to uphold immigration laws and this would be an economic boon for us.”

Indeed, some local governments are opting to remain in or even expand contracts with federal authorities for holding immigrants. Officials in Yolo County in Northern California voted this week to accept more than $2 million in additional federal money from the Office of Refugee Resettlement for holding immigrant children at a detention facility, overriding criticism.

“We need to approach each facility on a case-by-case basis to do what’s right for the young people involved,” said David Lichtenhan, vice chairman of the Yolo Interfaith Immigration Network, which urged the county to go forward with the contract. “The kids are vulnerable and could end up being moved into a district that’s less favorable to immigrants than ours. That’s an outcome we sought to avoid.”

© 2018 The New York Times Company