Flowing lava, the main draw of Hawaii’s historically most popular visitor attraction, reappeared Sunday night at Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park after a more than two-year absence and produced a steamy show attracting crowds through Monday in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic.

National Park Service officials raised concerns about people gathering without masks and venturing into off-limits areas of the park, which is open 24 hours a day.

The public is being advised to follow COVID-19 safety protocols at the park and to expect lines for parking at popular viewing areas around Halemaumau Crater.

“The return of lava to the summit of Kilauea is a natural wonder, but we need the public to be fully aware that we are in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic and to recreate responsibly, maintain social distance and to wear a mask,” Rhonda Loh, the park’s superintendent, said in a statement. “We want to keep the park open for all to experience this new phase of volcanic activity, and we need visitors to follow safety guidelines that keep everyone safe.”

>> PHOTOS: New Kilauea eruption at Halemaumau Crater

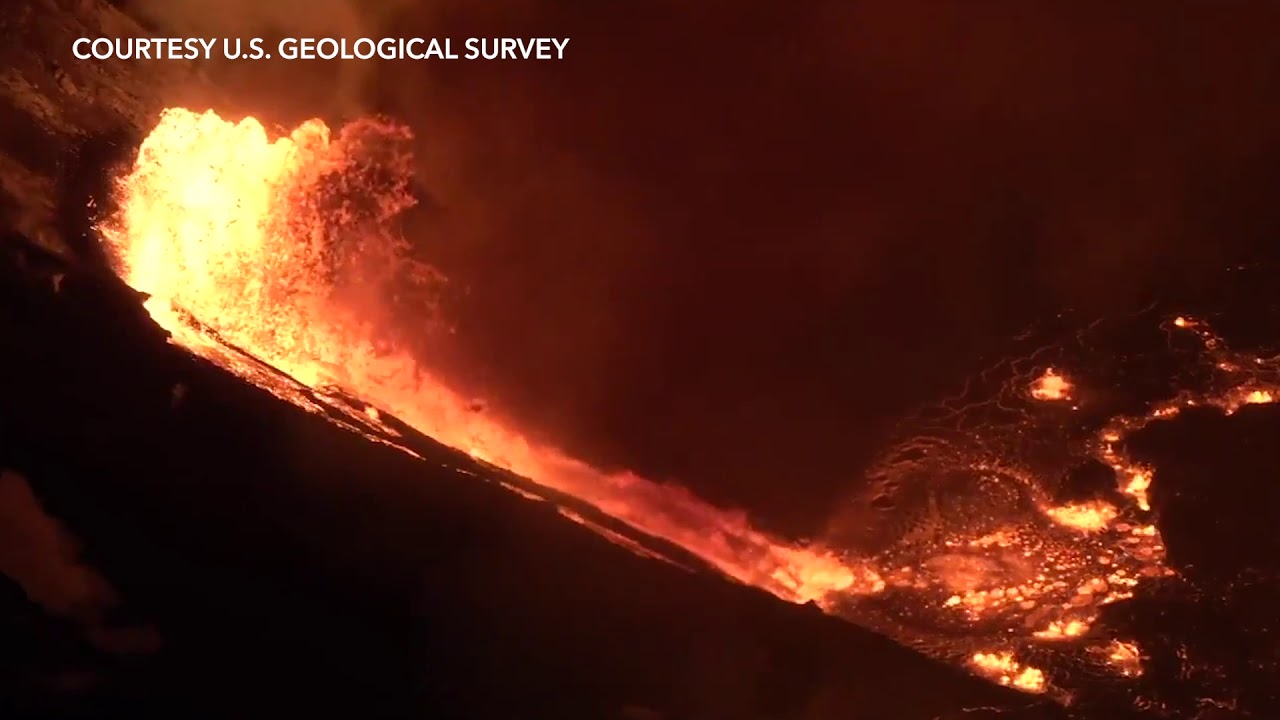

Three fissures opened along the sloped walls of Halemaumau, from which lava spouted into the air and ran down to the bottom of the roughly 1,640-foot-deep crater where the molten rock formed a slowly rising lake after boiling off a basin of water, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

USGS officials said the tallest lava fountain early on in the eruption was as high as about 165 feet and that the lava lake was roughly rising several yards an hour, though the eruption did not pose a direct public hazard because lava is completely contained in the crater.

These fissures and the lake cannot be seen from legal public vantage points in the park. But billowing clouds of steam, which at night reflect a red glow of the lava flowing below, became a spectacular attraction after the eruption was detected on USGS Hawaiian Volcano Observatory webcams at about 9:30 p.m. Sunday.

Bobby Camara, a longtime Volcano resident, drove to the Kilauea Overlook after a friend called him shortly after 10 p.m. Sunday, and he observed glowing plumes that he said were just as remarkable as the first eruption he saw of Kilauea in 1959.

“We could see big billowing Pele-colored clouds coming out of the crater,” he said.

Several vantage points for viewing the eruption activity at the park include Wahinekapu (Steaming Bluff), Kilauea Overlook, Keanakakoi, Waldron Ledge and other overlooks along Crater Rim Trail. The glow at night also could be seen from several miles away in some areas.

Rangers are present outdoors at the park daily and are available to answer questions, but are not leading tours because of COVID-19. Exhibits in the park’s visitor center are closed.

Jessica Ferracane, a spokeswoman at the park who also witnessed the eruption Sunday night, said about half the people she saw taking in the display were not wearing masks. She also said people were going into closed areas that include dangerous undercut cliffs.

“It was pretty stunning last night,” she said. “It’s exciting but we have concerns.”

Ferracane did not have a specific count of how many people flocked to Halemaumau on Sunday and Monday to see the show. She put the estimate in the “hundreds but not thousands.”

That compares with 5,000 to 10,000 people a day who were drawn to see extraordinary displays before mid-2018 when the crater floor was 280 feet deep and a lava lake could be seen from public overlooks.

The crater was drastically enlarged during an eruption of the volcano that began in May 2018 and included earthquakes and ash explosions at the summit while lava poured out of more than 20 fissures miles away in Puna where 6,000 acres of land was covered and more than 700 homes were destroyed.

After roughly four months, lava ceased flowing in Puna and ended 35 years of continuous eruption activity for Kilauea.

For the past several weeks, the observatory said scientists had recorded ground deformation and earthquake rates at the summit and upper East Rift Zone that exceeded levels observed since the end of the 2018 eruption.

Observatory officials said an earthquake swarm and ground deformation began beneath Kilauea’s summit around 8:30 p.m. Sunday, about an hour before lava fissures were seen. There also was a 4.4-magnitude earthquake centered about 8.7 miles south of Fern Forest near the Holei Pali area of the park at a depth of 4 miles about an hour after the eruption began.

The Hawaii County Civil Defense Agency activated its emergency operating center upon notification of the eruption, and the agency initially advised the public to stay indoors to avoid exposure to any ash fallout and to be aware of possible aftershocks.

Civil Defense Administrator Talmadge Magno said there were reports of minor ashfall in Pahala from the eruption Monday morning but no indication of any major disruptions.

All air quality monitor reports early Monday indicated minimal or no risk to the public.

Powdery to gritty ash composed of volcanic glass and rock fragments represent a minor hazard, according to USGS.

A more concerning hazard is volcanic gases coming from the crater, which National Park Service officials say present a danger to everyone and especially people with heart or respiratory problems, infants, young children and pregnant women.

Geology teams are on rotation monitoring gas concentrations as well as data feeds from tiltmeters and seismometers.

Research geophysicist Ashton Flinders of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory said the eruption currently poses limited hazards and that it’s unclear how long the current eruption will last.