Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell allowed to become law a $2.92 billion general operating budget that’s only about $60 million

less than the one he submitted Opens in a new tab

to the City Council in March

when the state’s economic

forecast was much rosier.

But Caldwell also expressed worries about the uncertainty of revenue collections that are supposed to pay for the city’s $9.2 billion rail project from sources seriously rocked by the impacts of the global economic downturn and the shutdown of the local tourism market caused by the coronavirus outbreak.

On the good news side, city Budget Director Nelson Koyanagi said several other developments triggered by the pandemic — including another one also related to rail — are helping soften

the blow of lower-than-forecast revenue collections.

The city is allowed to use about $81 million in coronavirus-related federal CARES transit funds (through the Federal Transit Administration) for TheBus and TheHandivan operational costs, allowing general funds originally programmed for those operations to be freed up for other uses, Koyanagi said.

Additionally, largely as a result of the pandemic’s impact on the rail project’s construction deadline, budget officials are now projecting they will be able to spend about $18 million less in rail operations costs in the coming fiscal 2021 budget year that starts July 1, Koyanagi said. City officials are now anticipating the first East Kapolei-to-Aloha Stadium segment of the project to begin operating in February or March rather than in December as originally forecast. Opens in a new tab

But Caldwell and Koyanagi also warned there’s a possibility that dramatic reductions in revenue in the coming year from property, general excise and hotel room taxes from what was originally forecast could cause the city to hit pause and reexamine its operating budget.

Because the bulk of the rail construction project is being funded through state general excise and hotel room taxes, the near halt to the state’s visitor industry as well as the unprecedented slowdown to the general economy could force the city to make some hard decisions.

The Honolulu Authority for Rapid Transportation last month said it expects at least a $100 million shortfall, possibly as much as a $200 million Opens in a new tab drop, in tax revenues due to the economic downturn.

At a Council Budget Committee Wednesday, HART Chief Financial Officer Roth Lohr reiterated the uncertainty of the revenue picture with Council members. “At this point in time, unfortunately, we don’t have an exact answer of how that will look like overall on the project,” Lohr said.

“We definitely are very concerned with the impacts of COVID-19, particularly in the visitor industry — the (hotel room tax) portion has pretty much dried up, and the GET has dropped significantly,” Caldwell said. “I think the impacts are going to be significant.”

While some have called for construction to stop at Middle Street, Caldwell said that’s not something he wants to see because ridership and revenue based on a full 20-mile line to Ala Moana are key factors in the project’s operations, the mayor said.

“The position of this administration is to keep the project going all the way to Ala Moana Shopping Center,” Caldwell said.

The city is already looking to Hawaii’s congressional delegation to help find funding to cover the revenue shortfall, the mayor said. Another possibility might be to defer building of some of the 21 planned stations, he said.

“There’s all kinds of things and there’s consequences to each one … but discussions are underway given the new realities we all face,” Caldwell said.

Much will depend on the bids that come in this summer for a public-private-partnership (P3) contract that will oversee operations of rail for the next 30 years in exchange for constructing the last segment of the rail guideway. Proposals are due July 23.

City officials also will be monitoring property tax collections from August and beyond, Koyanagi said. “That’ll give us a good idea whether the city revenues will be impacted going forward because if taxpayers start defaulting or falling behind on their tax payments, then we may have to start implementing some restrictions on the city’s agencies and restricting the budgets to make sure that we have enough funds to continue our core city services.”

Agency heads have not yet been ordered to make across-the-board budget cuts or institute hiring freezes, but have been told to come up with plans to reduce their budgets by up to 5% if necessary, Caldwell said.

Caldwell said his biggest priority is to maintain the current level of service of police, fire, emergency services and other first-responder operations and then “try to avoid furloughs as much as possible.”

“If we get into a situation where we have to cut back, the first thing we would look at regarding personnel would be not hiring new people,” Koyanagi said. “We’d just use that money to pay for other things.”

Council Budget Chairman Joey Manahan also said

August will be a key month for the city’s financial picture.

“We’re really going to find out come August … it depends on how the collections come in and whether people are going to ask for deferrals and what that would do,” Manahan said. “If people don’t defer indefinitely, then I think we will have enough money at least for the budget that we did put together.”

If not, Manahan said, the Council will have to come back and look at other options.

Some in the community, including the Waikiki Improvement Association, wanted the city to consider waiving property taxes for those hardest-hit businesses. Meanwhile, a bill introduced by Council members Carol Fukunaga and Ann Kobayashi that would have allowed businesses to defer paying property taxes Opens in a new tab was shelved.

Instead, in early May, Caldwell announced that the city will allow for August payments to be stretched out in installments over four months Opens in a new tab to make it easier for businesses and individuals.

“We could have done certain things that would have lessened the impact on people but would have had huge consequences (for the city’s financial picture) down the road after I leave and I believe that these tough times are going to continue for a while,” Caldwell said. “And therefore, decisions were made with a longer view rather than a shorter view.”

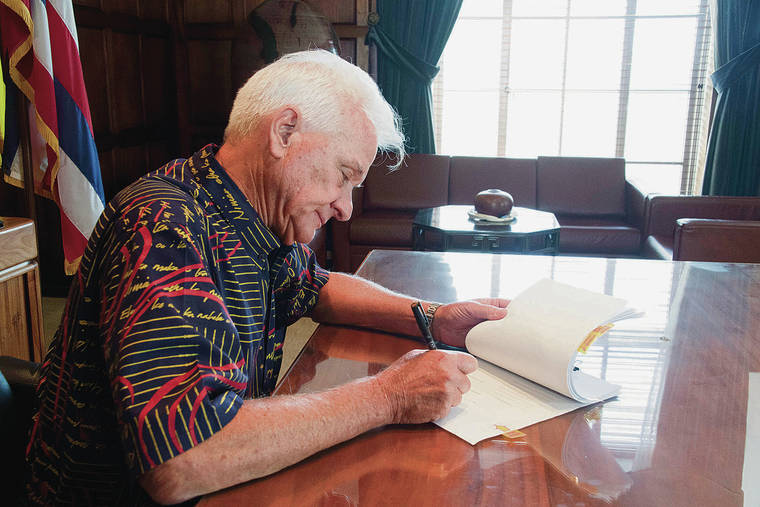

Caldwell, as he has in each of the seven years he’s been mayor, chooses to let the city operating budget, capital improvement budget and HART’s operating and CIP budgets, as well as other budget measures, become law without his signature due to a longstanding disagreement over the way they are worded. The practice predates Caldwell’s tenure as mayor.

Correction: The city budget becomes law without Mayor Kirk Caldwell’s signature. The photo caption in an earlier version of this story said the mayor signed the city budget into law.