“I am the king,” Muhammad Ali said in a voice that boomed through a hallway of the Hawaii State Boxing Commission.

But on a January day in 1981, when Ali sought and was, in effect, rejected for a boxing license in Hawaii, it was Robert M. “Bobby” Lee, a cigar-chomping, silver-haired commissioner who faced down the ex-heavyweight champ and promoters, to carry the day.

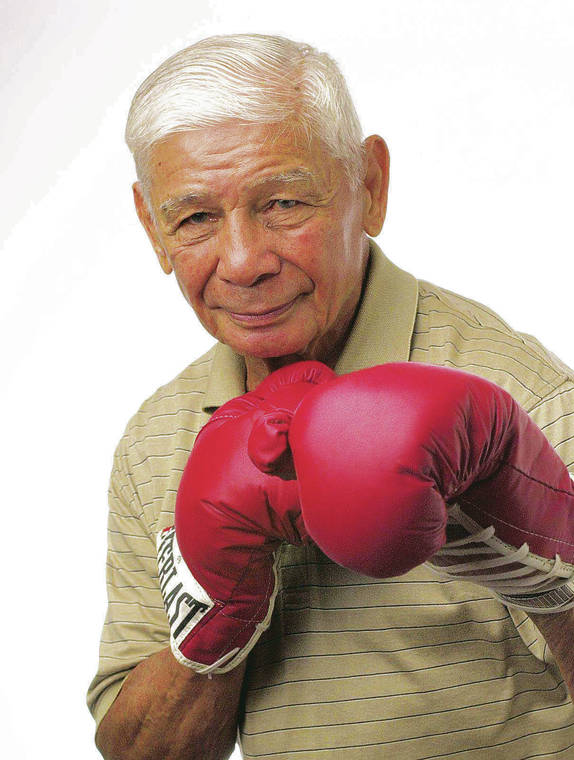

Lee, who died Wednesday at age 99 from what were described as natural causes, was a legendary figure in Hawaii boxing for more than a half-century.

His death was mourned on an assortment of boxing websites, including that of the World Boxing Association, an organization he served a two-term presidency with in the 1970s.

But for all his decades as the executive secretary of the Hawaii commission and as an international officer, Lee, who never had a pro fight, is best remembered for the “knockout” of Ali’s proposed bout here.

Three months after the aging Ali lost a decision to Larry Holmes in Las Vegas and was on the verge of being rebuffed for another fight there, he applied for a license here, ostensibly to fight European champion John L. Gardner.

Speculation was that the stop here was just to get a license, which would then permit his promoters to take the fight elsewhere.

Lee was three years into retirement in 1981 when he was urgently summoned to the state capitol by then. Gov. George Ariyoshi. “When I got there,” Lee said later, “They had a judge to swear me in and they gave me a piece of paper to take to the commission meeting to show that I was officially on the commission.”

Lee said, “The governor never told me to kill the fight, but I think he knew how I felt about it. (Ali) was deteriorating and people just wanted to use him and make money off him. We didn’t know then about his (Parkinson’s disease), but you could tell he’d already had enough.”

With Lee leading the charge, the commission voted 3-2 to defer the vote on the application until it could get some clarification about Ali’s status from the Nevada Athletic Commission.

But, as Lee knew, the deferral was, in effect, a rejection since Ali’s 39th birthday was in four days. By the time the statement from Nevada was received and an agenda posted for the new meeting under the state’s “Sunshine Law” Ali would be too old for a license under the rules then in force.

After also being turned down elsewhere, Ali eventually fought 11 months later in the Bahamas, where he lost to Trevor Berbick in what would be the final bout of his career.

“Bobby was the EF Hutton of boxing because he never said much, but when he did, everyone shut up and listened,” said Hubert Minn, chairman of the ring officials for the World Boxing Council and North American Boxing Federation. “He had a lot of integrity.”

Lee began boxing in Puukolii and the plantation circuit on Maui, where he was 41-4 as an amateur lightweight and welterweight. “The workers would bet on the fight and, when you won, you got some money,” Lee said. “A dime was pretty good money then. You could buy two cones of sushi for a nickel or a bowl of saimin.”

Lee liked to say, “I thought a whack to the chin was good fun. I wasn’t really smart and I wasn’t a very good athlete at some sports, but I found that I could fight and I figured if I ever wanted to earn recognition at something, it would have to be in boxing.”

After serving in the Army in World War II, he went to work with the then-Territorial Boxing Commission before being promoted to executive secretary in 1951. He also held senior positions with the World Boxing Council, Orient and Pacific Boxing Federation and NABF.

“I’m not saying I was this great, self-made man,” Lee said in a 2004 interview, “but whatever I became, I owed to boxing.”

His death leaves the good guys’ corner in the sport a lot emptier.

Services are pending.

Reach Ferd Lewis at flewis@staradvertiser.com or 529-4820.