‘Take Every Wave’ tags along on Hamilton’s wild ride

COURTESY SUNDANCE SELECTS

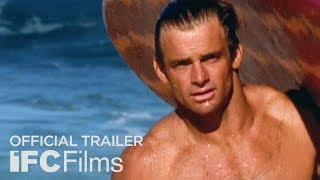

Laird Hamilton’s life is documented in “Take Every Wave.”

“TAKE EVERY WAVE”

***

(Not rated, 1:58)

Against the grain is the only way Laird Hamilton knows how to go. A dynamic, dominating personality, he became one of surfing’s central figures despite refusing to compete professionally, and he revolutionized the nature of the sport not once, but twice.

In fact, Hamilton’s story is so filled with drama and personal and psychological complexity, not to mention spectacular visuals of waves upward of 100 feet tall, that it compels attention whether surfing means anything to you or not.

Even more unlikely, “Take Every Wave: The Life of Laird Hamilton” is directed by Oscar-nominated Rory Kennedy, best known for committed social-issue documentaries like “Last Days in Vietnam,” “Shouting Fire” and the Emmy-winning “Ghosts of Abu Ghraib.”

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with top news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

“Honestly, initially I said no,” Kennedy said when the film debuted at Sundance. “With the world falling apart, why would I be doing a film about a surfer?”

What Kennedy came to see and what “Take Every Wave” demonstrates without doubt is that Hamilton’s personal journey is extraordinary enough in its scope and pushing-the-limits achievements.

Though sitting still appears to be close to unendurable for Hamilton, he completed hours of candid, emotional interviews, as did his oldest friends (even those he is estranged from) and his wife, Gabrielle Reece, a fitness authority and former world-class volleyball player.

In addition to footage shot for the film by Alice Gu and Don King, “Take Every Wave” had access to Hamilton’s personal visual archive, and the resulting imagery of him on the water — including his celebrated August 2000 ride at Teahupo’o, Tahiti, which is considered “the most intense wave ever surfed” — is simply astonishing.

As written by Mark Bailey and Jack Youngelson and expertly edited by Azin Samari, “Take Every Wave” starts with the near present and pulling back to reveal Hamilton’s restless past. He is first met on Kauai in 2016, looking at some historic El Nino-produced swells. “I’ve been waiting a lifetime to ride this thing out here,” he says, and that is no exaggeration.

We are also briefly introduced to the world of foil boarding, Hamilton’s radical obsession for the past few years, where the surfboard is attached to a metal hydrofoil the way foils are connected to America’s Cup yachts.

This pioneering is the second one Hamilton was involved in, for he was also the key figure in tow-in surfing, where personal watercraft are used to tow surfers into immense waves that were previously thought to be unsurfable. The waves, one surf journalist says, are “high enough for this guy to be insane.”

Immune to panic — “He has a fear deficit,” says friend Buzzy Kerbox — Hamilton also is, says Gerry Lopez, “a naturally gifted surfer,” blessed with balance and a sensitivity to what the ocean is doing.

More than that, after his single mother moved to Hawaii and, as a toddler, he introduced her to future husband and accomplished surfer Bill Hamilton, Hamilton grew up surrounded by the best surfers in the world.

Good as he was, Hamilton, interested in the experience for its own sake, always refused to enter competitions, instead fooling around with personal watercraft. That led to his epiphany about tow-in surfing. He and some friends developed the sport at Jaws on Maui.

Not that any of this was easy. Hamilton is upfront about what an incorrigible terror he was as a kid, and his father, who became a stepfather before he was 20, is equally honest about the corporal punishment he visited on his stepson.

Hamilton is remarkably candid about all his activities, including the hard feelings some of his actions produced in his close friends. And both he and his wife are honest as well about the nature of and strains on their marriage.