LAHAINA >> Maui County plans to let some survivors back into the devastated historic Lahaina fire area Monday and Tuesday, but evacuees have mixed feelings about what they’ll see and how they’ll feel.

Casandra Villasenor, 40, needs to retrace her panicked escape from Front Street on Aug. 8 that ended with her in the ocean to survive the inferno in order for her to separate what actually happened to her from all of the stories of survival and death that she’s heard and shared in the weeks since the fire, which killed 97 people.

“I’ve lost track of time,” Villasenor said. “I don’t even know how long I spent in the harbor until I came out of the water. I need to be able to walk it again. It’s something I need to do. I want to go.”

She hopes the worst is over but won’t know for sure until she gets back in.

Villasenor lost hearing from the sound of exploding boats while floating in the ocean and said, “I’ve seen dead bodies everywhere. The water was on fire everywhere.”

Retracing her steps to separate her experience from others “would be closure,” Villasenor said. “People have been telling their story from where I was at and I need to make sense of it all.”

Maui County said Wednesday night that Lahaina property owners and residents of the area along Kaniau Road will be allowed in Monday and Tuesday as long as they can show proof of residency or ownership in order to acquire vehicle passes, which will be available from Saturday through Sunday at the Lahaina Civic Center.

Two vehicle passes per dwelling will be allowed but drivers will be stopped at a checkpoint to gain entry.

Friends Desiree Deter, 47, and May Lee, 43, worry about how much time they’ll have to experience the emotions they expect to feel when they return to their separate, obliterated rental units that they each considered their best homes ever.

Deter first reviewed the site following the Aug. 8 fire and said, “I snuck in and started crying. All the memories were assailing me. It was very overwhelming.”

Deter hopes county officials let residents return as often as they want, for as long as they want. And she hopes to bring in a metal detector to look for her dead mother’s jewelry and a silver dollar given to her by her grandmother.

Lee has yet to see what’s left of her one-bedroom cottage on Shaw Street but knows that it’s gone.

“It’s demolished,” she said. “It’s pulverized. It was all wood.”

Lee expects the experience of seeing the remains “to be very emotional. I know it’s going to be devastating.”

Like Deter, Makaio Martin, 35, also went to the ruins of his Lahaina home after the fire and videotaped the destruction to the three homes that his family lived in, along with their destroyed vehicles.

He and his wife and three children lived in a single-family home that they shared with his brother-in-law, who owned it, sister-in-law and their children.

There were four different families in one home, Martin said.

Following the fire, Martin inspected the wreckage and said, “everything was burned to the ground. I don’t want to go back. There’s nothing there, literally nothing.”

Asked if his visit provided any sense of closure, Martin said: “No. No. No.”

Martin grew up in Hilo and moved to Lahaina to find work at the age of 17.

As a handyman with no home of their own, Martin and his wife, Joanna, now plan to move to Olympia, Wash., with their children — ages 3 to 13 — and live with Joanna’s sister.

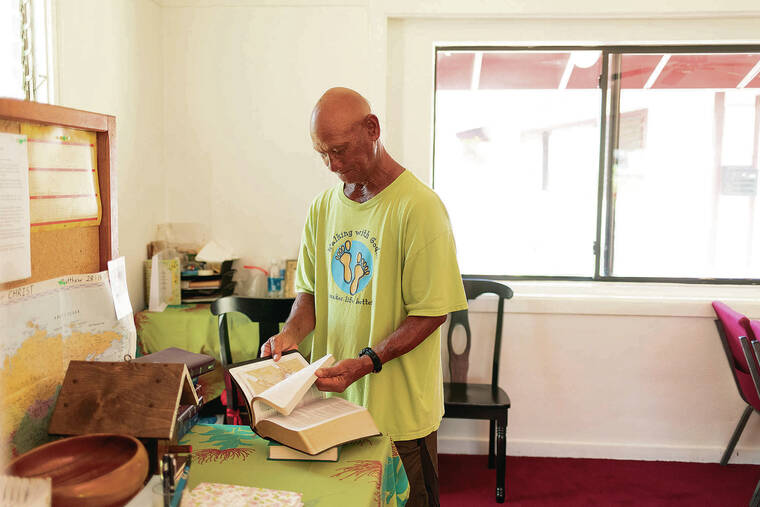

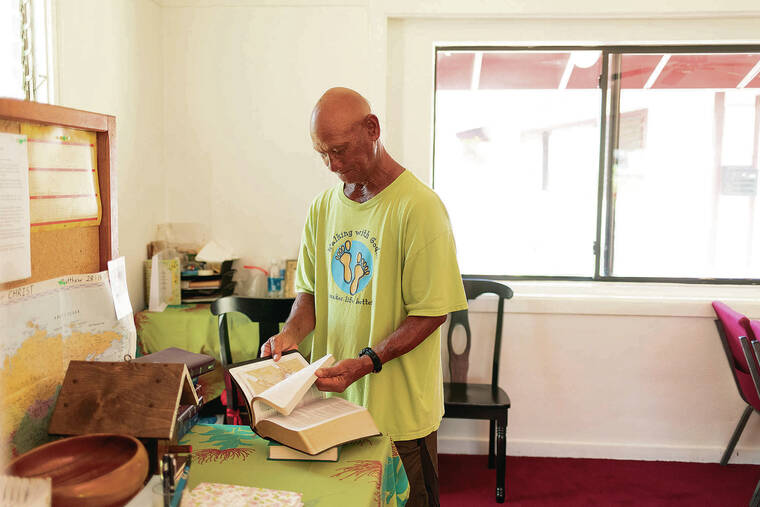

Kahu Glenn Kamaka, 72, wants to see what’s left of the two-bedroom, two-bath condo in the five-building Opukea at Lahaina Condominiums project that he shared with his girlfriend, Elaine Sumibcay.

Two of the Opukea condo buildings were destroyed — including the one that Kamaka and Sumibcay lived in — while three were spared.

Kamaka continues to feel guilt that he was not able to save their two cats, Kai Ala and Mahina.

“Had we gone in, we would have burned,” Kamaka said. “I think it’s best that we look at it.”

Kamaka said he does not know how he’ll feel once he returns to the scene of the fire but said, “I want to make sure we are sorry for what we did.”

Like other survivors, Kamaka said, “A lot of us want to grieve. Most of us need to grieve. There’s no closure. No, not yet.”

Kamaka has pleaded with cleanup crews to show respect for the dead and wants to see for himself how they are operating — especially with Native Hawaiian cultural beliefs that the souls of the fire casualties remain in the area, and with their deaths resulting from so much trauma and violence.

“It’s very sensitive,” said Kamaka, who is of 75% Hawaiian ancestry.

But Lei La‘anui, 61, has no interest in seeing what’s left of the place where she was born and raised and where many of her family lost their homes, including her son, Kewehi Ko, 43, whose Front Street apartment that he shared with his wife and their five children was destroyed.

“I already know what it looks like,” said La‘anui, who now lives in Waihee. “No, I don’t need to go there to see it.”

Shawna Dunn oversees free grocery distributions to Lahaina fire evacuees at the Napili Park Noho Distribution Center and said survivors are divided over their interest in going into Lahaina to see the devastation first-hand.

“It’s 50-50,” she said.

Like a funeral for a loved one, Dunn said “some people want the closure to see the remains. For other people, it’s just too painful.”

Others worry about ongoing warnings that the air around Lahaina remains contaminated with substances including arsenic and asbestos.

Maui County Council member Tamara Paltin chairs the council’s Disaster, Resilience, International Affairs, and Planning Committee, represents West Maui and has heard a lot of feedback from Lahaina fire evacuees on whether they want to see the devastation for themselves or not, including from some residents looking for evidence that their belongings have been looted, which Paltin acknowledged would be hard to prove during a visit.

“They’re asking, ‘Who’s going to be accountable if their stuff gets stolen?’” Paltin said at the Napili Park Noho Distribution Center. “There are lots of worries about looting.”

For others, she said, seeing the remnants of the devastation would “definitely” give them closure.

Others cite reasons for not going in, including questions about what breathing contaminated air could mean for their long-term health.

“A lot of people do have health concerns,” Paltin said.

And for untold numbers of Lahaina residents — especially older ones who spent their lives in the historic town — Paltin said they have no interest in seeing what the deadliest U.S. wildfire in over a century did to the community they love.

“They want to remember it like it was,” Paltin said. “It’s just too painful.”

But Randal Rodrigues, 40, plans to visit the plantation home on Kahula Place where he was born and grew up in and lived in with his mother, Evon, who inherited the home from her father, who built it.

In all, four families — seven relatives and five children — lived in the two-story house that Rodrigues hoped to inherit and pass down to his own three children some day.

“My mom lived in it when she was pregnant with me,” Rodrigues said while sitting on a bench at Hanakaoo Park with his wife, Valerie. “It was going to go to us and then my kids.”

Before the fire, the house was home to his mother, brother, uncle and their families.

Now it’s all gone.

“I still pay rent to my mom because she has to pay the mortgage,” Rodrigues said.

When they’re finally allowed in to review the property, Rodrigues said the family has agreed to return together to support one another through whatever emotions they will experience.

His mother, Evon, Rodrigues said, “wants to go in as a family. It’ll give us a little closure.”

At age 69, Rodrigues said his mother has vowed to rebuild his childhood home — no matter how long it takes.

And so has Rodrigues, who spent his entire life there.

“Check back in 10 years,” he said. “I’ll be here.”