Chris Kaiakapu loves fishing off of West Kauai, where Native Hawaiians have gathered for generations to practice subsistence fishing. But he’s worried that the federal Missile Defense Agency’s proposal to build a $1.9 billion missile defense radar at the Navy’s Pacific Missile Range Facility could result in less access at productive fishing grounds.

“We’ve pretty much had very limited to no access since 9/11 in 2001, so I have no reason to doubt they wouldn’t further those restrictions in the Kokole Point

area where it’s proposed,” said Kaiakapu. “It’s a huge shoreline fishery for us westside residents and Hawaiians. From Kekaha all the way around to Polihale is some of the most productive shoreline fishery grounds. … It would just further limit our cultural and subsistence resources.”

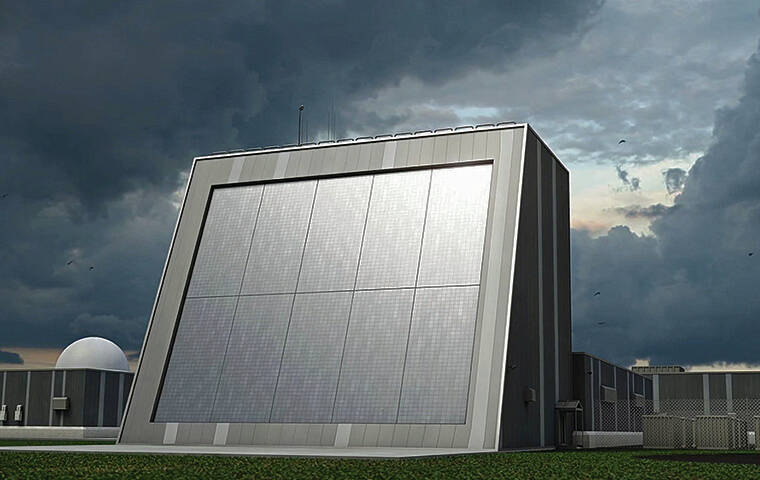

While the project’s supporters maintain that it’s critical to Hawaii’s security and will provide

an economic boost, some Kauai residents have countered that in addition to disrupting traditional fishing, construction of the proposed Homeland Defense Radar-

Hawaii could potentially cause environmental damage, further strain a struggling housing market and even hurt the tourism industry.

Military leaders are also split on its value — the Pentagon has spent years trying to defund it.

In December 2018 the Missile Defense Agency awarded Lockheed Martin a contract to develop, build and deliver the HDR-H after the false alert missile scare had rattled the state in January amid high tensions with North Korea. North Korea announced last week that it had successfully tested a hypersonic missile, and has conducted several missile tests this month.

Military planners have spent years trying to find a home for

the HDR-H. After scouting potential sites on Oahu, they are now eyeing the Pacific Missile Range Facility as a favored site for the project. The Missile Defense Agency is in the “scoping phase” of the development process and drafting an environmental impact statement — a document that lays out potential positive and negative impacts on surrounding communities.

Casey Reimer, a pilot for Jack Harter Helicopters and president

of the Hawaii Helicopter Association, said, “There’s a lot of impacts that we’re concerned … are not going to get addressed, or maybe not listened to, in the EIS process.”

Among them is a potential expansion of no-fly zones around PMRF. With helicopter tours serving as a sizable draw for Kauai’s tourism industry, more restrictions could seriously impede those flights, Reimer said. He also said the project could affect aerial contract work, such as battling brush fires on the Garden Isle’s west side.

Military activities in Hawaii are under heightened scrutiny after fuel from the Navy’s underground Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility — situated above a critical aquifer — contaminated the service’s drinking water system, which serves 93,000 people on Oahu. During a Tuesday congressional hearing on the crisis, U.S. Rep. Kai Kahele, D-Hawaii, told commanders, “We are at an inflection point for … the state of Hawaii’s public trust and relationship with the United States military moving forward.”

In its latest defense spending bill, Congress ordered the Navy to propose alternative fuel storage sites for the Pacific Fleet’s war reserve. The bill also authorized $465.5 million for military construction projects in Hawaii, including

$75 million in continued funding for the HDR-H. Defense spending plays a critical role in Hawaii’s economy, making up at least 7.7% of the state’s GDP.

Hawaii’s congressional delegation has for years fought for continued funding of the radar despite repeated Pentagon efforts to zero out funding under President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump. Though the HDR-H has been on U.S. Indo-Pacific Command’s funding wish list for years, the Pentagon has cited problems finding a viable location and a desire to look at alternative sensor systems in the Pacific as reasons for putting funds elsewhere.

In 2019 the estimated

cost of the entire facility was about $1 billion. But as planners began considering logistical challenges of moving materials and building it on the rugged terrain of proposed sites, the price tag

estimate nearly doubled.

When the spread of COVID-19 shut down much of Hawaii’s tourism industry, state leaders leaned on defense dollars to help prop up the floundering economy. In January 2021 the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism recommended creation of a defense industry group that would bring together Hawaii companies, military commanders and state agencies. That move prompted the establishment in May of the Hawaii Defense Alliance. The alliance is managed by the Hawaii Chamber of Commerce’s Military Affairs Council.

Some advocates for ramping up defense spending here assert it can yield tech jobs, which can be filled by Hawaii college graduates who might otherwise leave for the mainland to pursue job opportunities. Such a workforce in Hawaii, they contend, could help grow nonmilitary tech jobs, such as those in cybersecurity, thereby further diversifying the economy and reducing dependence on tourism.

While the HDR-H has been touted as an opportunity for locals to secure tech jobs, some Kauai residents worry that instead both construction and operation of the facility would be handled mostly by transplants with the specialized skills the military wants — potentially displacing locals.

“Even the largest building contractors on Kauai build principally wood homes, not steel military installations,” said Kip Goodwin, a member of both the Kauai Alliance for Peace and Social Justice and the executive committee for Kauai in the Sierra Club’s Hawaii chapter. “HDR-H would be contracted to Oahu and mainland contractors who historically and traditionally bring their own employees, who don’t require prior training to do the skilled work,” he predicted.

Moreover, Kaiakapu, the

local fisherman, said, “What little jobs and opportunity

it would provide would be

negated by the influx of

transplants, which only exacerbate our housing crisis here (with low-income residents struggling to keep pace with rising housing costs) and our traffic problems.”

Though top leadership at INDOPACOM has pushed for building the radar, another snag involves an internal

debate over which military branch should sacrifice already limited space in Hawaii to actually take on the project.

On Oahu, plans to build it at the Army’s Kahuku Training Area would take a significant chunk of the land that soldiers and Marines use to train. Previously, PMRF was ruled out as a site on the advice of Navy officials, shifting the search to Oahu before numerous problems found at proposed sites prompted military officials to again put Kauai on the table.

“Operators at the (PMRF) base voiced their concerns that the radar’s electromagnetic emissions would interfere with the electronics of their operations,” said Goodwin. “That’s why the site chosen is as far away as possible at the narrow southern tip of the base. That site puts the complex only a few hundred yards from the ocean and at minimum elevation.”

Though planners have proposed building an elevated platform to protect

the radar from tsunamis and hurricanes, Kaiakapu and other critics argue the location poses risks to the facility itself and the surrounding environment.

“The potential for pollution or contamination during the construction process

or during operation, if there’s some sort of leak

or a tsunami causes some sort of breach or contamination of the shoreline, is another very concerning possibility,” said Kaiakapu.

The project faced opposition on Oahu over concerns that proposed sites overlapped ancient Hawaiian cultural areas and could threaten habitats of endangered species. In January 2021, Kahele told Oahu’s North Shore Neighborhood Board that he would oppose building the radar on Oahu, but he has since come out in support of building the facility on Kauai.

Responding to Kahele’s stance, Goodwin said, “We hope he is realizing that the west side community has historically received what the rest of the island didn’t want: the oil-fired generating plant, the landfill, a polluting shrimp farm and the chemical seed industry.”

Kahele told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, “I await the results of the EIS, once it’s been completed. But I continue to support the Homeland Defense Radar-Hawaii. As demonstrated by North Korea (last) week, a ballistic missile threat to Hawaii is still very real.”

U.S. Sen. Mazie Hirono, D-Hawaii, has been the project’s most vocal and aggressive champion. During a tense exchange in a March 2020 congressional hearing, she grilled then-Defense Secretary Mark Esper about its exclusion from the Trump administration’s defense budget request.

In response, Esper said the exclusion didn’t necessarily mean the project was canceled. However, he added, “If I develop a system and can’t put it somewhere, it has no effect. It’s wasted money.”

Hirono raised the issue

of the radar’s funding again when the Biden administration also left it out of its requested budget. During a September hearing on the military’s chaotic evacuation from Afghanistan, she told Biden’s Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin that “the president has touted the

Afghanistan pullout as necessary to free up time and money to deal with near-peer competitors like Russia and China, but that stated rationale is somewhat, I think, at odds

with the administration’s budget.”

Hirono’s office did not

offer any comment in response to repeated requests by the Star-Advertiser.

Hawaii residents on both Oahu and Kauai who oppose the HDR-H have pointed to the Pentagon’s own waning interest in the project. In particular, some have argued that space-based missile detection

systems currently in development could possibly render the facility redundant or obsolete in the three to five years it’s expected to take to build it.

With the Pentagon, “under two different opposing (White House) administrations,” declining to fast-track the project for various reasons, Kaiakapu said, “Don’t waste our time or taxpayer money or, more importantly, our land. Don’t waste Hawaiian land on this project.”