For the second year in a row, the Defense Department is reportedly planning to zero out funding for the $1.9 billion Homeland Defense Radar-Hawaii — a move that could represent a death knell for the costly radar that’s now seen as less of a priority among evolving missile threats and competing demands.

The Pentagon previously redirected funding for the powerful sensor intended for North Korean threats to other efforts, officials noted. Last year it did not budget any money for the Hawaii radar and a more than $1 billion Pacific ground-based radar that could have gone to Japan.

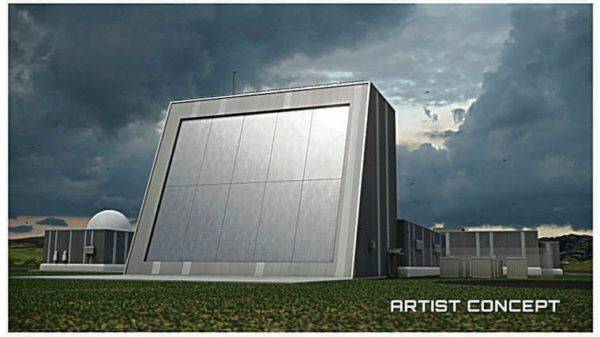

Kahuku Training Area on Oahu and the Pacific Missile Range Facility on Kauai are the two locations still under consideration for the radar, which is planned to have a single face up to 85 feet tall.

Hawaii’s congressional delegation has steadfastly supported construction of the radar for the defense of the Aloha State as the Pentagon has repeatedly taken funding out.

Congress most recently pumped $133 million back into the effort with the National Defense Authorization Act of 2021 permitting the Missile Defense Agency to continue limited planning.

“MDA is engaged in

advanced planning studies and preparing an environmental impact statement for the siting and development of the (radar), should a deployment decision be made and is funded,” the agency said in a Q&A on its website.

Two officials with knowledge of the planning who did not want to be identified because of its sensitivity told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser that the Pentagon again is zeroing out funding for Homeland Defense Radar-Hawaii.

A spokesperson for U.S. Sen. Mazie Hirono, a Hawaii Democrat, said in an email that she “will carefully review President Biden’s defense budget when he submits it to Congress in early May. As a senior

member of the Armed Services Committee, Sen. Hirono plays a central role in considering and providing oversight of the president’s requests. She will continue to advocate for projects and programs that keep Hawaii safe.”

Heather Cavaliere, a spokesperson for the Missile Defense Agency, said, “it would be inappropriate to discuss” fiscal 2022 budget issues prior to the official release.

Meanwhile, U.S. Rep. Kai Kahele, who is on the House Armed Services Committee, echoed similar thoughts. “The Congress is not in receipt of the full president’s budget request for fiscal year 2022. Therefore, it is premature to comment on the proposed funding for the project,” he said.

Kahele, also a Hawaii Democrat, added: “However, I do strongly support the Pacific Deterrence Initiative and the investment plan

outlined in” an an assessment put together by Adm Phil Davidson, head of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command.

Davidson submitted the report to Congress with a request for $27.3 billion in extra funding from fiscal 2022 to 2027 to counter an expansionist China.

The most important move the United States can make, Davidson said, is to invest $1.6 billion in a 360-degree air defense capability for Guam — noted as the “most crucial operating location in the western Pacific” — and whose defense remains Indo-Pacific Command’s No. 1 unfunded priority.

Davidson has called for an Aegis Ashore facility — a test version of which operates on Kauai — to provide that missile defense capability. As part of the total he also requested $2.2 billion for a “constellation of space-based radars.”

One official said it’s possible for the Pentagon to add in a last-minute funding request for the Hawaii radar, or for Congress to add more money in piecemeal fashion. But the ground-based sensor also been left out of the Pentagon’s five-year planning known as the Future Years Defense Program.

Production lines and delivery dates are impacted by the lack of inclusion in the plan.

Testifying last year before a House Armed Services subcommittee, Missile Defense Agency Director Vice Adm. Jon Hill said the United States was at an “inflection point” that was complicating missile defense.

“Ballistic, hypersonic and cruise missiles are becoming more capable of carrying conventional and mass

destruction payloads farther, faster and with greater accuracy,” he said in prepared remarks.

Russia and China continue to develop advanced missiles designed to overfly air defense sensors and fly below ballistic missile sensors, he said.

Missile defense will “continue to leverage space-based, ground-based and maneuverable sea-based sensors,” Hill said. “Yet there will never be enough terrestrial-based sensors to track maneuvering missiles in large numbers. If we are to outpace the threat, we need a persistent space-based global sensor capability.”

In January, Northrop Grumman and L3Harris received contracts for satellite prototypes to track hypersonic and ballistic missiles.

In the meantime, Hawaii relies on a network of smaller radars as well as the Sea-Based X-Band Radar should a North Korea threat become imminent — and experiences a gap in radar coverage while doing so.

A 2018 Defense Department report said the Pacific Discriminating Radar Program included the Hawaii and Pacific radars and was intended to address “requirements for a near-term persistent solution against advancing threats and closes capability gaps throughout the Pacific region.”