David Shapiro: Kaneshiro and Mitsunaga maybe not yet in the clear

GEORGE F. LEE / GLEE@STARADVERTISER.COM

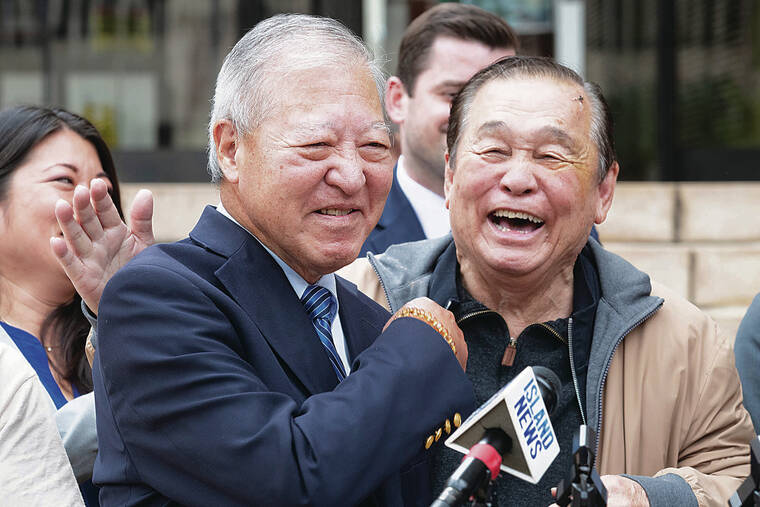

Former Honolulu Prosecutor Keith Kaneshiro, left, and co-defendant Dennis Mitsunaga celebrated outside U.S. District Court in Honolulu on May 17 after being found not guilty in their corruption trial.

Ghosts of O.J. Simpson are appearing following the failed federal bribery prosecution of former Honolulu Prosecutor Keith Kaneshiro, businessman Dennis Mitsunaga and others.

After a jury acquitted defendants on allegations Kaneshiro was bribed with some $40,000 in campaign donations to bring allegedly bogus theft charges against Mitsunaga’s former employee Laurel Mau, she’s filed a civil lawsuit using evidence from the criminal case to accuse the defendants of federal civil rights violations.

A civil suit seeking monetary damages applies a less stringent burden of proof than a criminal case and could potentially cost taxpayers, as Mau named the city a defendant as Kaneshiro’s employer.

Victims’ families in the 1995 Simpson murder acquittal used a similar tactic to persuade a civil jury to hold the football star responsible for the deaths of his estranged wife and her friend, awarding them millions of dollars in damages.

A civil case requires only a preponderance of evidence to prevail instead of proof beyond reasonable doubt for a criminal conviction.

Jurors in the federal prosecution found insufficient evidence of a clear quid pro quo between Kaneshiro and Mitsunaga. In a civil trial, Lau’s attorneys would attempt to focus more sharply on whether their actions violated her civil rights.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

It wasn’t only federal prosecutors whose eyebrows were raised by the the Mau theft case, which culminated a lengthy employment dispute between the architect and Mitsunaga’s company that involved her firing after filing sex and age discrimination complaints, a fight over unemployment pay and civil litigation.

When the theft charges alleging Mau had done unauthorized side jobs on company time reached the state Circuit Court in 2017, Judge Karen Nakasone sternly dismissed them, accusing Kaneshiro’s office of relying on information provided by Mitsunaga with little independent investigation.

Nakasone scolded prosecutors that the “highly unusual” and “irregular” case was a “threat to the judicial process.”

Similar concerns were meticulously detailed in the federal prosecution of Kaneshiro, Mitsunaga and the others.

Federal attorneys presented evidence that police weren’t asked to investigate Mitsunaga’s claims against Mau, as was customary, nor did the prosecutor do his own corroboration.

Two veteran deputy prosecutors found weak evidence and recommended against bringing charges. Kaneshiro gave the case to a third deputy, a recent hire, who sidestepped bringing the case before a grand jury or a judge in a preliminary hearing, instead charging via a controversial information complaint.

Even then, a judge initially turned it down because of a lack of independent investigation by law enforcement, at which point an investigator in the prosecutor’s office was asked to sign a statement of findings he had not personally investigated.

The federal verdict centered mostly on whether there was enough evidence of an explicit corrupt agreement between Kaneshiro and Mitsunaga.

A more root issue, as in the cases involving former Honolulu Police Chief Louis Kealoha and his prosecutor wife, Katherine, is about one of the most alarming abuses of power: attempting to use official authority to put an innocent person in jail.

A civil rights lawsuit may prove the more appropriate venue to determine if this is what happened to Mau.

Reach David Shapiro at volcanicash@gmail.com.