Hall of Famer Bill Walton, one of basketball’s most eccentric characters, dies at 71

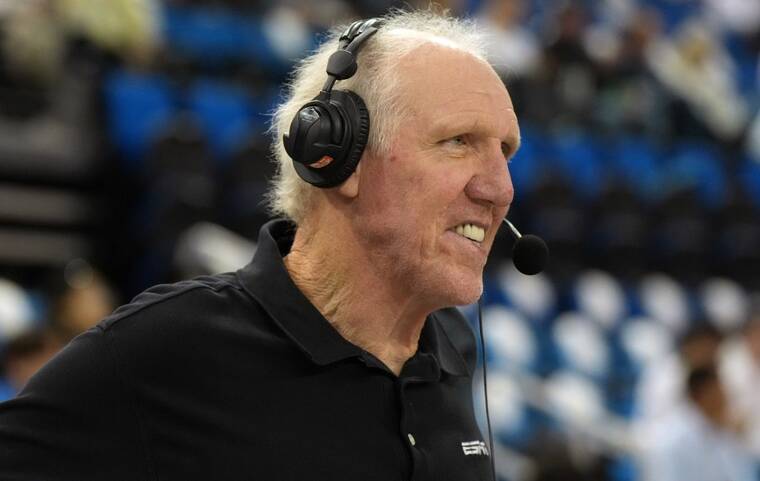

KIRBY LEE-USA TODAY SPORTS

ESPN analyst Bill Walton during the Dec. 22 game between the UCLA Bruins and the Maryland Terrapins at Pauley Pavilion presented by Wescom in Los Angeles. Walton, a two-time national champion at UCLA and two-time NBA champion, died today after a prolonged battle with cancer. He was 71.

Bill Walton, a Hall of Fame center who authored a career that was triumphant and tragic, as well as colorful and controversial, died today at the age of 71 after a battle with cancer, the NBA announced.

Walton was regarded as one of the most dominant and versatile centers to ever play, which translated to two state titles with Helix High in La Mesa, Calif., two NCAA titles at UCLA and two NBA titles, one with the Portland Trail Blazers in 1977 and one with the Boston Celtics in 1986. In 1993, he was elected into the Naismith Hall of Fame, and in 1997, the NBA named him one of the Top 50 players of all time.

“Bill Walton was truly one of a kind,” NBA commissioner Adam Silver said in a statement. “As a Hall of Fame player, he redefined the center position. His unique all-around skills made him a dominant force at UCLA and led to an NBA regular-season and Finals MVP, two NBA championships and a spot on the NBA’s 50th and 75th Anniversary Teams. Bill then translated his infectious enthusiasm and love for the game to broadcasting, where he delivered insightful and colorful commentary which entertained generations of basketball fans. But what I will remember most about him was his zest for life. He was a regular presence at league events — always upbeat, smiling ear to ear and looking to share his wisdom and warmth. I treasured our close friendship, envied his boundless energy and admired the time he took with every person he encountered.

“As a cherished member of the NBA family for 50 years, Bill will be deeply missed by all those who came to know and love him. My heartfelt condolences to Bill’s wife, Lori; his sons, Adam, Nate, Luke and Chris; and his many friends and colleagues.”

When Walton flew into Portland, Ore., in October 2009, he was surprised to find tears streaming down his cheeks.

As the legendary center looked out the window of the plane, he was flooded with memories. He had returned to Portland many times since he left in 1979, the result of a hastily requested trade. But for some reason, this time, at age 56, he was overcome with emotions. There was the satisfaction and appreciation of a team coming together to win the 1977 NBA title. The agony of multiple surgeries on his feet and ankles. The anger and confusion of how his medical care was handled. And the regret of how he handled it all.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

The next day, before a Trail Blazers home game, Walton explained his emotions to a group of reporters.

“I’m here to try and make amends for the mistakes and errors of the past,” Walton said. “I regret that I wasn’t a better person. A better player. I regret that I got hurt. I regret the circumstances in which I left the Portland Trail Blazers’ family. I just wish I could do a lot of things over, but I can’t. So I’m here to apologize, to try and make amends, and to try and start over and make it better.”

Ironically, Walton was in Portland to be feted. Oregon governor Ted Kulongoski was honoring him with the Governor’s Gold award, given annually to four people or organizations who have made great contributions to the state. And the Trail Blazers had invited him to headline a fundraising event. But as the governor and the franchise prepared to celebrate one of its greatest athletes, Walton was revealing the complexity behind his legacy.

Ten years later, on another return to Portland, he looked back on that 2009 flight into Portland.

“It was very sad,” Walton told The Athletic. “I always try to self-reflect, and when you are living a life that is on stage, on camera, out in front, the minute it gets quiet, that’s when the true answers come to you … when it’s too late.”

Walton’s greatness on the court was unquestioned. In high school, Walton’s teams won their final 49 games. At UCLA, he was the NCAA’s player of the year for three consecutive seasons (1972-74), a span that included a string of 88 consecutive victories. In the NBA, he won the 1978 Most Valuable Player award with the Trail Blazers and the 1986 Sixth Man of the Year award with the Celtics.

But behind many of his triumphs was the tragic disappointment of injuries. Walton had 39 surgeries during his playing career, mostly on his feet and ankles, which caused him to miss 762 games over 13 seasons. Three times he missed an entire season because of injury. In his autobiography, Walton wrote that his biggest regret was playing hurt.

“I didn’t let pain be my guide,” Walton wrote. “I didn’t say, ‘If it hurt a lot, don’t play.’”

He said he suffered a knee injury on the playground as a youth and was never the same.

“My legs were pretty much shot by the time I got to the NBA in 1974,” Walton wrote. “I peaked when I was 12.”

When healthy, few were more versatile or more dominant. He was a brilliant passing big man, both in the half court and by initiating the fast break after a rebound with an outlet pass. He was 6-foot-11 and long, which helped him become an effective shot blocker. Those who played with Walton called him the ultimate teammate, who helped elevate their game. Still, never was Walton more ready to step to the forefront than in big games.

In the 1973 NCAA title game against Memphis State, Walton had 44 points, 13 rebounds and seven blocks while making 21 of 22 shots in UCLA’s 87-66 win. Walton made four other shots that were disqualified and ruled offensive goaltending because of a then-NCAA rule prohibiting dunking. The previous season, in 1972, Walton had 33 points in the national semifinal, then led all scorers with 24 points in the title game, helping UCLA beat Florida State 81-76, which earned him the first of his two Most Outstanding Player awards.

In Game 6 of the 1977 NBA Finals, Walton had 20 points against Philadelphia, plus 23 rebounds, seven assists and eight blocks as Portland clinched the series and won its only NBA title. Walton in the series averaged 18.5 points, 19 rebounds, 5.2 assists and 3.7 blocks and was named Finals MVP.

His most gratifying moment, Walton said, came at the end of his career, after he was traded from the Los Angeles Clippers to the Boston Celtics. Accepting a reserve role backing up Robert Parrish, Walton played in 80 of the 82 regular season games and 16 of the Celtics’ 18 playoff games. Averaging 7.6 points, 6.8 rebounds and 2.1 assists in 19 minutes, Walton beat out Milwaukee’s Ricky Pierce and Sacramento’s Eddie Johnson for the Sixth Man of the Year award, and helped Larry Bird and Kevin McHale win another title. Walton called it “my greatest personal playing accomplishment.”

“I never had a better time playing,” Walton wrote in his biography. “Aside from winning, my favorite moments on the court came when I was out there with Larry Bird. It’s safe to say our styles were complementary.”

In a four-part documentary on Walton called “The Luckiest Man on Earth,” producer Steve James interviewed Bird about playing alongside Walton. Bird told James that Walton was as good as anybody when healthy.

“When Larry Bird said that, I mean, Larry Bird is not a guy who just throws around compliments,” James told The Athletic. “When he said he was one of the best ever, I said: Centers?

“And he said, no. Players.”

The next season would be Walton’s last, limited to 10 games because of injury.

“When he was right, I think he was the best center playing the game,” said Dave Twardzik, a guard on Portland’s title team.

In the turbulent 1970s, with the Vietnam War raging and Watergate eroding the confidence in the United States government, Walton became more than just a basketball player. He became a voice in the counter-culture movement.

He was arrested in May 1972 on the UCLA campus for protesting the escalation of the Vietnam War, and a picture capturing Walton sitting down on Wilshire Ave. with arms peacefully raised before his arrest, was circulated widely in newspapers and magazines.

Walton told author Tom Shanahan that he believed in peaceful protests then, and always.

“Protesting is what gets things done,” Walton said. “The drive for positive change requires action. The forces of evil don’t just change their ways.”

And in 1975, a week after his second season with the Trail Blazers, Walton took part in a San Francisco news conference defending friends Jack and Micki Scott, who at times lived with Walton in Portland. The Federal Bureau of Investigation were pursuing the Scotts for harboring members of the Symbionese Liberation Army, who had kidnapped Patty Hearst, and the Scotts disavowed any wrongdoing. Walton asked the world to “stand with us in the rejection of the United States government” while also calling the FBI “the enemy.”

The Trail Blazers were outraged by Walton’s comments, and owner Herman Sarkowsky, team president Larry Weinberg, and executive vice president Harry Glickman issued a statement.

“The Portland Trail Blazers deplore Bill Walton’s statement calling for the rejection of the United States Government. The United States is the freest and most democratic nation in the world. We and the people throughout the world recognize this,” the Blazers said in their statement. “The American system, despite its imperfections, has been and continues to be the have which oppressed people throughout the world yearn to reach. We believe the National Basketball Association is an example of the opportunities available to people under the system of government, and Walton, more than most, has reaped extraordinary benefits from this system.”

At the time, it was not unusual for an athlete to speak out on political or social issues. Arthur Ashe, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Bill Russell, Muhammad Ali … they all took stands and were unafraid to voice their opinions. They all were Black. Walton was White.

“He was arguably the most outspoken White superstar, certainly in college, of that time,” James said. “To this day, there aren’t many White players of stature who speak out with regularity about capitalism … politics … whatever. Bill was a real outlier, in part because he was White, and in part because athletes at that time were trying to toe the line. They were viewed as culturally conservative.”

Years later, Walton argued against the notion that athletes should focus on their sports and not voice their opinions.

“Sports encompasses all aspects of life,” Walton told Hal Bock of The Associated Press in 1991. “It’s unfortunate when people use the argument that it is not a platform for politics … I believe you can’t stop and put sports in a vacuum. Just because people are involved in a special thing like sports, that doesn’t prevent them from taking a position.”

For the younger generation, Walton may only be known for his second career: broadcasting, where he was an over-the-top, and at times zany, color commentator for college and NBA games.

The irony was Walton grew up with a stutter and struggled with interviews in college and the NBA. When Walton was 28, he said he met New York Knicks broadcaster Marty Glickman, who gave him a series of tips on how to correct his stutter, which included slowing your thoughts down, reading out loud and chewing sugarless gum to strengthen jaw muscles. He also told Walton to identify the sounds that gave him trouble — for Walton it was words with D, H, S, Th and W — and find books or articles with those words and practice.

Walton, who would later become a paid public speaker, often cited in his presentation that learning to speak was “my greatest accomplishment … and your worst nightmare.”

In 1990, Prime Ticket Network hired Walton as an analyst. Soon, he was everywhere. He had stints with NBC, ABC, CBS, FOX, ESPN, Turner Sports and most recently was providing color commentary for ESPN broadcasts of Pac-12 basketball. In 2001, he received an Emmy for best live sports television broadcast. No matter the network, or the stage, Walton was always spouting outrageous, off-the-wall commentary.

Awful Announcing, a sports media website, made a list of Walton’s most outlandish broadcast moments. A sampling:

>> “Yesterday, we celebrated Sir Isaac Newton’s discovery of gravity. Today, Fabricio Roberto is defying it.”

>> “If you ever think you’re too small to make a difference, you’ve never spent a night in bed with a mosquito, or you’ve never played basketball against Taylor from Utah — No. 11 in your program, No. 1 in your heart.”

>> “John Stockton is one of the true marvels, not just of basketball, or in America, but in the history of Western Civilization!”

>> “Tonight’s start was electric. Just both teams riding quasars all the way to the top of the mountain to the promised land!”

When Walton descended upon Portland on that October day in 2009, another factor led to his emotional state: He was a reborn man.

During 2007 and ‘08, Walton was absent from the airwaves. No television. No radio. No appearances. He was on his back, in misery, and contemplating suicide.

“I had been in the hospital, on my death bed, wanting to kill myself. For years,” Walton said in 2009. “I was in a terrible spot.”

In February 2009 he had a spinal fusion, and it not only eased his pain but also gave him a fresh outlook. It’s why he was so eager to repair his relationship with the Trail Blazers, and why he once again became an avid bike rider, and once again started attending what he called “church” — concerts of the Grateful Dead, of which he has attended more than 1,000 shows.

He was happy, with a feeling of accomplishment, and he wanted to spread the word. He called himself the “luckiest man in the world” and he believed it.

“When you face death, it changes you,” Walton said. “And you are never the same again.”

This article originally appeared in The Athletic Opens in a new tab.

© 2024 The New York Times Company