The perilous state of American Samoa’s last tuna cannery is an outcome that experts have long warned about. An international shift in the fishing industry, largely driven by countries with lower workforce standards and pay and subsidized infrastructures, makes U.S. competition in the cannery industry unavailing.

In desperate attempts to cling to the last of what was once four canneries in American Samoa, some industrial fishers and cannery operators are trying to blame Pacific conservation efforts as the culprits. Despite the anticipated demise, it is disingenuous to pit the vitality of the ocean against American Samoa’s livelihood. This divisive approach offers false hope that the territory’s cannery can somehow survive if we don’t protect the health of the Pacific Remote Islands (PRI).

Located in the middle of the Pacific ocean, Howland, Baker, Jarvis and Wake Islands; Johnston and Palmyra Atolls; and Kingman Reef are home to some of our planet’s last wild and healthy ocean ecosystems. The islands, atolls and reefs also hold rich voyaging and cultural history among indigenous Pacific Islanders.

In 2009, President George W. Bush protected parts of the region’s waters by establishing the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument. In 2014, President Barack Obama expanded the monument. Last year, to further ensure protection of these fragile areas President Joe Biden supported the Pacific Remote Islands Coalition’s request to create a national marine sanctuary, further expanding protections to 777,000 square miles. The sanctuary designation process is now underway.

Unfortunately, PRI has become the scapegoat for those who want the territory to remain dependent on a dying cannery industry.

Look at the trend: At its peak, American Samoa was home to four canneries. Today, there is one.

While convenient to blame conservation efforts, for close to two decades a mix of factors has made the operation of canneries in the U.S. no longer financially viable — or even close to competitive. Other countries entered the canning market and operate with low workforce standards and pay. Those canneries have become much cheaper alternatives for China and others with an exponentially growing presence in the fishing industry.

The writing on the wall is stained: It is not in American Samoa’s or the United States’ best interest for the territory to have a disproportionate economic dependency on StarKist, a South Korean-owned cannery. It’s time to invest and advance forward-thinking solutions that benefit American Samoa, the U.S. and our planet.

To diversify its economy, American Samoans should be in the driver’s seat, shaping and realizing opportunities they believe are right for them and their long-term future. There are many opportunities to explore. A regenerative tourism model could support local entrepreneurs and grow small businesses. Neighboring Western Samoa already draws tourists from as far away as Europe. Alia (small boat) fishermen, impacted by the industrial fishing industry, could benefit by providing local establishments and communities with fresh, sustainably caught fish.

Today, the National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa is the largest in the National Marine Sanctuary System, protecting magnificent nearshore coral reefs and offshore open ocean waters. With this incredibly diverse marine life, American Samoa would be an ideal site for a Central Pacific marine science center, nurturing a new generation of local scientists.

An expanded American Samoa-based presence would also provide a critical counterbalance to China’s growing influence across the Pacific region. The closed cannery sites and docks in Pago Pago Harbor are existing locations and infrastructures that American Samoa can provide to support Coast Guard vessels in the interest of national security. New jobs and other economic opportunities would follow to support that expanding presence.

It is time for American Samoa to embrace its potential and invest in a blue economy that can realize a thriving future. American Samoa deserves better.

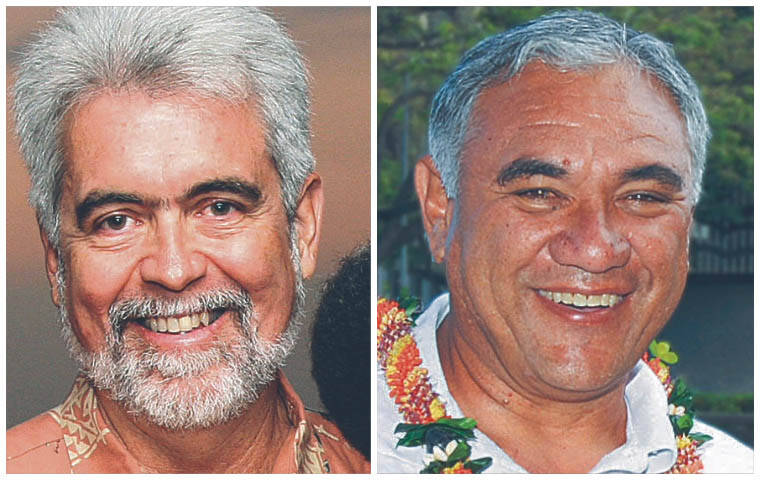

Rick Gaffney, top, is a recreational fisherman and former Western Pacific Fishery Management Council member; Hawaii island resident William Aila is a Native Hawaiian fisherman and former chair of the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources and the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands.