The Navy is asking the

National Marine Fisheries Service to “modify” its regulations to allow for more injuries to marine mammals during Pacific training.

The NMFS authorizes the Navy an “incidental take” — a calculation of the number of times the government

believes Navy operations could result in marine life getting harassed, injured or killed in a certain area even if sailors are working to mitigate the impact.

The Navy’s current operating permit for its Hawaii- Southern California Training and Testing Study Area expires in 2025 and allows up to three large whales to be killed in “ship strikes” —

fatal collisions at sea. As of 2023 the Navy has hit that limit through incidents off Southern California.

But in a public legal notice posted online to the Federal Register on Monday by the U.S. Department of Commerce, the agency said the Navy has asked the NMFS to retroactively amend the regulations to allow for two more fatal ship strikes to large whales before the permit expires.

The Navy also put forth new mitigation policies in its request that it says should prevent such ship strikes. However, the fact that

the service asked for

permission to change regulations to allow for more has drawn criticism from environmental watchdog groups.

“The Navy’s main response to hitting and killing whales is to ask for permission to harm more whales. It’s nonsensical and extremely disappointing,” said Kristen Monsell, legal director at the Center for Biological Diversity’s oceans program. “A rubber stamp from the federal government to allow whale ship strikes won’t help endangered whales recover. To truly protect whales and comply with the law, the Navy needs to implement speed limits requiring ships to slow down in important whale habitat.”

“The Navy and entire federal government need to start doing everything they can to reverse the catastrophic impacts the United States is having on our increasingly fragile environment, and on our planetary climate security,” said Wayne Tanaka, director of the Sierra Club of Hawaii. “Instead, after Navy vessels struck at least three whales in the last two years, they are now simply asking

permission to run over even more whales — animals that can actually play a key role in carbon sequestration and climate mitigation.”

In 2021 the Navy announced it would review its policies after an Australian navy destroyer participating in a U.S.-led multinational exercise off California dragged two dead fin whales under its hull into San Diego, where the animals were dislodged from its hull. The Center for Biological Diversity filed a notice of intent to sue the Navy.

Navy officials had long contended that they would know if they had fatally struck a whale, but the 2021 incident indicated there could be more impacts than they had known. The Endangered Species Act requires the government to reevaluate its data if new information or factors it hadn’t considered come to light.

A Pacific Fleet spokesman told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser the Navy had requested to amend the permit “as a cautionary acknowledgement that some probability of ship strike, although low, could still occur over the remaining Hawaii-Southern California Training and Testing (HSTT) Study Area authorization period through December 2025. … This is predicated on a revised summary of the probability of future ship strikes in the approximately two years remaining in the HSTT authorizations following the Navy ship strikes in the

California portion of HSTT during 2021 and 2023.”

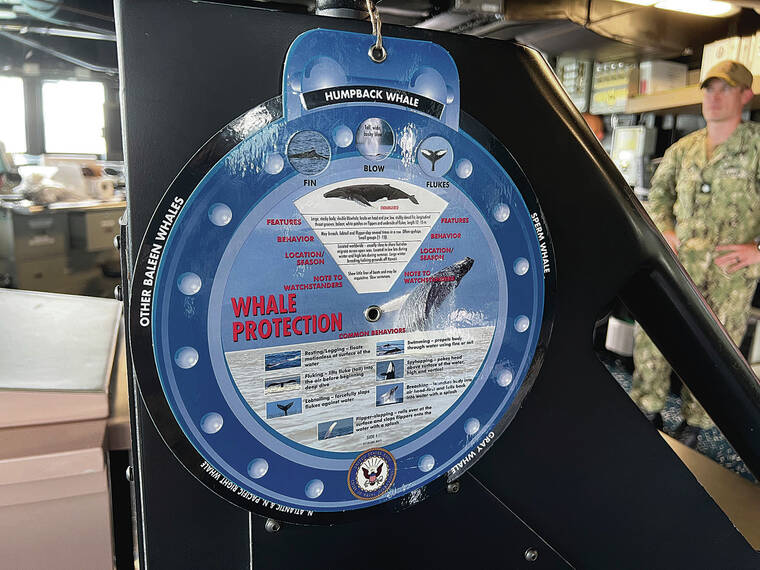

Under the existing permit, Navy personnel at sea must acknowledge “mitigation zones” for marine mammals and are instructed that “if marine mammals are observed, Navy personnel must maneuver to maintain distance.” Ships have a logbook aboard, and sailors are supposed to log any sighting of marine mammals spotted near their vessels.

“The Navy takes its environmental stewardship responsibilities seriously and has protective measures in place to avoid ship strikes,” said the Navy spokesman, who added that the Navy is working to better track whales and share reports of sightings with other ships and units operating in the Pacific.

“Additional marine mammal refresher training for operational units has also been implemented since these strikes,” said the Navy spokesman. “These measures are in addition to the long-standing standard procedures already employed, including the posting of trained Navy lookouts at all times on the ship and using the Protective Measures Assessment Protocol to inform of mitigation required in specific activities.”

But one of the main asks from environmentalists — requiring ships to slow down in known habitats — is off the table.

The legal notice said that in the modified permit NMFS is “emphasizing that Navy personnel should consider reducing speed (as mission or circumstances allow) when maneuvering to avoid marine mammals, though this modified measure does not require reduction of vessel speed for reasons,” adding that “requirements to reduce vessel speeds would have significant direct negative effects on mission effectiveness.”

“Ship strikes are a top threat to whales and the Navy can help prevent these tragedies by slowing down their ships through important whale habitat,” said Monsell. “Without more meaningful mitigation, we’ll only see more dead whales. That the Navy is asking for permission to kill more shows it has little faith in

the efficacy of existing

requirements.”

“The few new measures NMFS and the Navy are proposing are grossly inadequate,” Monsell added. She noted that many of these measures come into effect only if the whales is observed by sailors on the ships.

The Navy considers the Pacific its top-priority area of operations amid increasing tension with China. The competition between China and the U.S. has had both geopolitical and ecological consequences across the

region.

Much of the focus has been on the South China Sea, a critical waterway that more than a third of all international trade moves through. China claims nearly the entire sea as its exclusive territory, over the objections of neighboring countries, and has built bases on disputed reefs and islands to assert those claims. Satellite imagery suggests these construction projects are having a

profound environmental impact, but independent scientists haven’t been able to conduct research up close.

In Hawaii the U.S. military is facing increasing scrutiny over its environmental impact in the islands. The Monday legal notice mentioned a March 25, 2022, incident in which a beaked whale stranded in Honaunau Bay and bystanders intervened to turn the animal off the rocks, allowing it to swim back out of the bay on its own.

“Locals reported hearing a siren or alarm type of sound underwater on the same day, and a Navy vessel was observed from shore on the following day,” the notice stated. “The Navy confirmed it used continuous active sonar (CAS) within 50 km (27 nmi) and 48 hours of the time of stranding, though the stranding has not been

definitively linked to the

Navy’s CAS use.”

The notice said the NMFS and Navy explored the idea of new mitigation areas to protect marine mammals, including “consideration of new mitigation areas based on newly identified (biologically important areas) in Hawaii,” but that the Navy ultimately concluded establishing those areas would be “impracticable given overlap with critical Navy training areas in the (Hawaii Range Complex).”