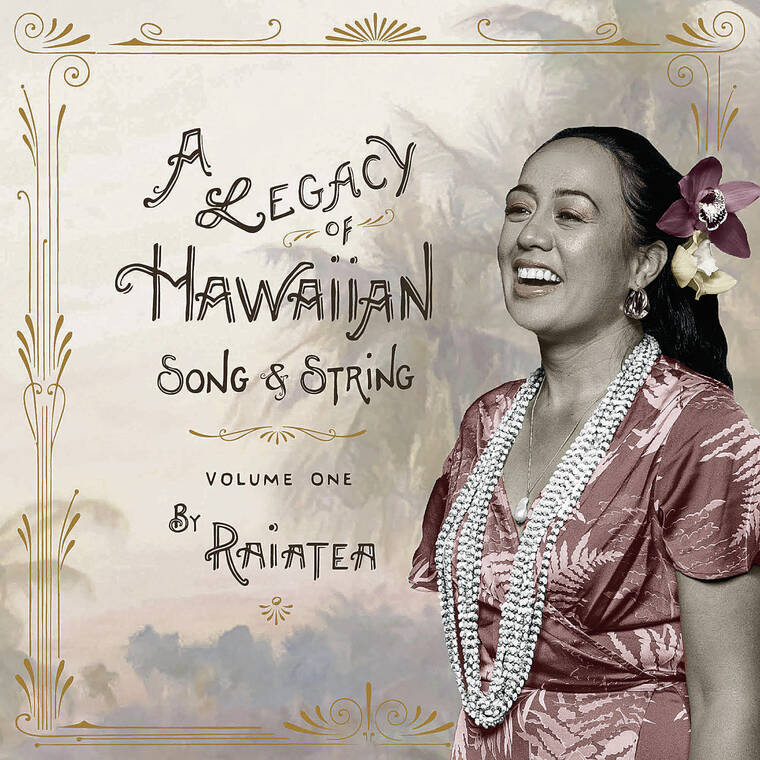

In the final decades of the Hawaiian monarchy, and for a decade or two afterward, the violin, viola, cello, zither, autoharp and Western flute were integral parts of Hawaiian music. Now, Raiatea Helm and Kilin Reece are bringing that sound into the 21st century with her newly released album, “A Legacy of Hawaiian Song &String Volume One.”

Molokai born and bred, Helm is a multi-Na Hoku Hanohano award-winning singer and the foremost female Hawaiian falsetto vocalist of her generation. Reece, a luthier by profession, has an encyclopedic knowledge of the music of the Hawaiian string band era — which ran from the mid-1800s to the first decade of 20th century — and particularly the musical legacy of Mekia Kealakai, a songwriter and bandmaster of the Royal Hawaiian Band. The first two songs on the album, “Lanakila Kawaihau” and “Nu‘uanu Waipuna,” are by Kealakai.

Helm says that the strings were the thing that hooked her into the project.

“A while back I had three goals,” Helm said. “One of them was to sing with the Honolulu Symphony. And I did. That was my introduction to the strings, and I liked those instruments.”

“It started with our work on (the) “Sovereign Strings” (concert) in 2019,” Reece said. “We wanted to take the history farther, and we wrote a grant to the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation and were awarded a two-year grant cycle to do heavy, heavy research delving through all the newspaper translations … and then also do Zoom meetings with other descendants of this generation of Hawaiian musicians that I’ve become in contact with. It’s been a good solid three years of digging into the history with her.”

Helm describes selecting and recording the songs as a learning experience.

“We had a list of 15 to 17 songs for the album, and then we decided to put some on the side because, like, maybe this song is not serving this time and purpose. You put your dream list together — the songs and musicians and guest artists you want — and then you work your way. It’s putting those pieces together.

“The song that resonates with me in this time in my life, and as well with many people, is ‘He Mele Lahui Hawai‘i’ (“Song of the Hawaiian Nation”),” she said. “I just learned that song, and there are just a lot of emotions behind that. Like, why did it take so long for me to discover it, but then it gives you something to look forward to when you do your music and you find your purpose.”

“He Mele Lahui Hawai‘i” was composed by Lili‘uokalani in 1866 when Kamehameha V wanted an entirely Hawaiian national anthem to replace one that used the melody of the British national anthem, “God Save the King.” Lili‘uokalani’s song was Hawaii’s national anthem until Kalakaua and Henri Berger wrote “Hawaii Pono‘i” in the 1870s.

Several other classics on the album were composed by Kalakaua and Lili‘uokalani’s royal siblings, Leleiohoku and Likelike.

At the contemporary end of the musical timeline, Helm, Reece and co-producer Dave Tucciarone include “Keao‘opuaikamakaokanalu,” written by Kainani Kehaunaele.

“Her track was actually the last one (we recorded),” Helm said. “I think it was very fitting because a lot of the legacy of “Hawaiian Song &String” ties in with this idea of Hawaiian kingdom. This is something that Kamakoa Lindsey-Asing, the musician who arranged Kainani’s song and did almost all the music on that track, said. He’s so deep when he thinks philosophically, it’s like opening up an old book of (historian and scholar) Samuel Kamakau, and he mentioned that these songs were a part of when the alii were here.

“But Kainani’s song is connected to that (theme) too, because it is about a princess and she came from an alii line that was ancient … We hear the stories of Pele (and) Poliahu … but there are so many folks we never hear of.”

Lindsey-Asing’s arrangement of “Keao‘opuaikamakaokanalu” also shows that contemporary songs can be performed in the older Hawaiian style.

“This project really seeks to honor the composers and musicians of (the monarchy), Reece said. “A second layer of meaning is really to show how they laid the groundwork for everything that we know today as blues, bluegrass, country, jazz (and) Western swing. To make the point musically that traditional Hawaiian music has been around before those other genres had really taken form. The Royal Hawaiian Glee Club string tradition took the Royal Hawaiian band brass band repertoire and synthesized it with a diversity of stringed instruments that was unprecedented in the world.”

Beyond the historical context of the project, Helm enjoyed what she describes as the “intimacy” of working with various combinations of string instruments.

“The emphasis on the voice, I learned that through my experience in the music, specifically with Keola Beamer,” she said. “He was the one that encouraged me to just try and sing with me and the ukulele. I felt that was so plain, but you don’t know unless you try it so I started to embrace that intimacy. It’s not an emptiness but it’s a sacred space that you’re experiencing as an artist — and perhaps for the listener too. That’s just something that I got to appreciate through just being in on the gig.

“It’s a part of that self-discovery. Music serves as tools in our lives, and whether we’re young or growing old, whether we’re together with someone or apart from someone, it’s a very spiritual and emotional thing.”

Annotation by Noah Ha‘alilio Solomon, Hawaiian language instructor at the University of Hawaii-Manoa, provides valuable background information on the individual songs and the album’s broader themes.

Solomon’s participation almost didn’t happen. When Reece contacted him, Solomon was writing his Ph.D. dissertation on revitalizing the use of the Hawaiian language in daily conversation.

“I didn’t know if I could accept it … but as soon as I heard these tracks — Kilin sent them to me and I pressed play — I was transported. Inspired music inspires people and I was inspired,” Solomon said. He added that “as someone actively participating in the revitalization and reclamation of Hawaii, one way we can do that in a pretty efficient way is to look at these mele and these compositions as the standards of excellence. They’re really great examples of elevated, sophisticated, poetic, lyrical language that still until today serve as a standard.”

Looking long term, Reece says the album, and the nonprofit Kealakai Center for Pacific Strings he founded in 2019, is documenting the sound of Hawaiian string band music, and the impact it had on mainstream popular music on the mainland and in many other parts of the world.

“I think what I’ve been able to bring to this is a really focused perspective through the instruments and through the lineage of these instruments — whether it’s the Fender Stratocaster or the Martin “Dreadnought” (guitar) or steel string guitars — that we can trace (back) to the influence of this generation of Hawaiian virtuoso, multi-instrumentalist musicians.”