Residents recount harrowing tales in Lahaina, Upcountry

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARADVERTISER.COM

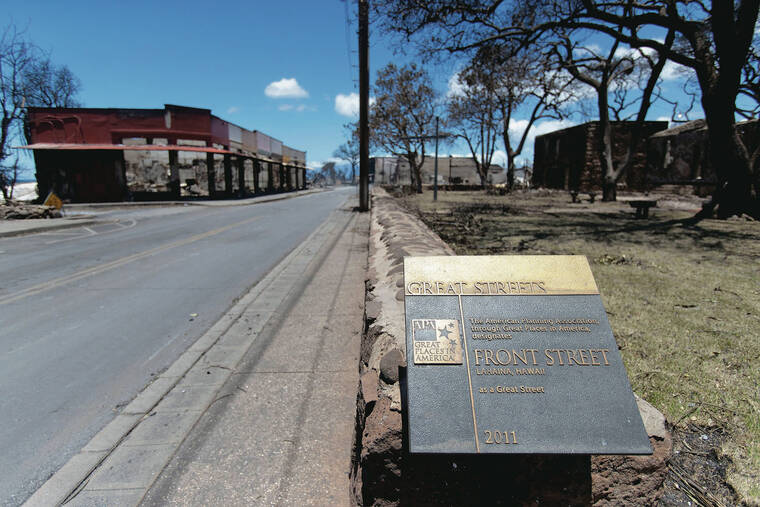

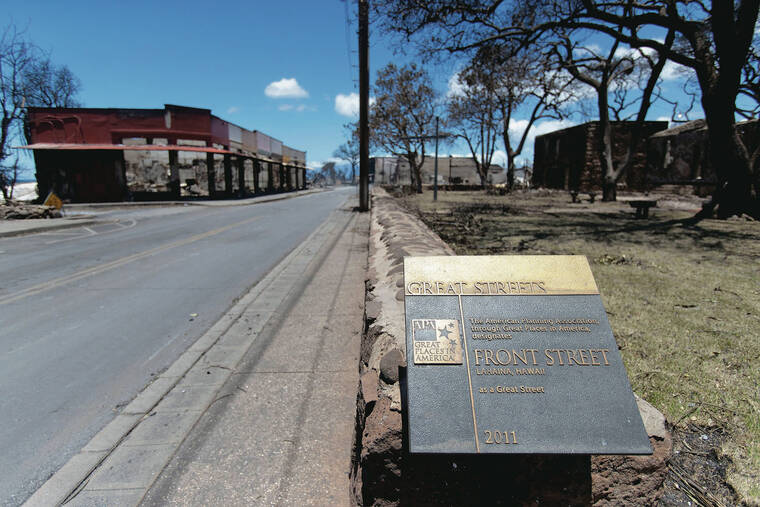

Charred structures along Front Street remained Saturday where thriving businesses once stood.

COURTESY REESE AND JENNIFER COLDAGELLI

Reese Coldagelli, with his wife, Jennifer, owned BanyanTreats, an ice cream and yogurt shop in Lahaina.

COURTESY ROBERT LOERA

Robert Loera, in his Maui Toy Works store in Lahaina. The Coldagellis and Loera experienced loss of electricity before the fire destroyed their businesses.

COURTESY ROBERT LOERA

Counterclockwise from right, Robert Loera with his wife, Barbara, and their grandnieces Lila and Kelly.

COURTESY PHOTO

Sharon Nakama:

The Baldwin High music teacher had gotten separated from her parents and had no means to communicate with them

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARADVERTISER.COM

A “Great Streets” marker remained Saturday on Front Street in Lahaina.

A harrowing escape through a burning downtown Lahaina. A lifetime of making others happy coming to a bittersweet end. Cautious relief, and an odd memory of times past.

These are the experiences of three Maui residents who lived through the horrific wildfires that swept through Lahaina and Upcountry last week.

Two years ago, Reese Coldagelli purchased BanyanTreats, an ice cream and yogurt shop located across the street from the town’s famous banyan tree. Early on Tuesday, the power had gone out in Lahaina, so he and his wife, Jennifer, went out to cover up the desserts, hoping to keep them cold until the power was restored.

They took a rest back in their condo on Baker Street, and when they awoke, they saw “the sky was full of smoke,” Reese Coldagelli, 33, said. The danger quickly escalated.

“All of a sudden there was fire raining down, and sparks the size of quarters flying through the air, lighting every single thing it touched on fire,” he said.

The streets were jammed with cars, and they knew they couldn’t drive out, so they grabbed some essentials and fled on foot.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

“You couldn’t see 10 feet in front of your face,” Coldagelli said. “There were people passed out in their cars from smoke. We could hear vehicles blowing up. There were transformers blowing up, propane tanks blowing up. It was absolutely what it would be like if you were in a war zone, or the last moment you would be alive.”

Cars refused to stop for them, and they wound up walking for four hours to Honokawai, 7 miles north of Lahaina.

“We were prepared to be on the beach for awhile, homeless,” Coldagelli said, “but for the grace of God” they were able to connect with friends, who offered them a place to stay.

Their lives, meanwhile, are in shambles.

“We were about to buy the condo we were living in, but that burned to the ground with everything. … all of our honeymoon stuff, all these little knickknacks that just meant the world to us that we’re never going to replace,” Coldagelli said.

He’s found that “at least 60%” of his workers had lost their family homes. “And these are all just high school students that are graduating this year. It was supposed to be their first day of school,” he said.

Fate to the wind

Wind has played a big role in Robert Loera’s life. “I love wind,” he said. “Even though I turned (his Lahaina shop) into a modern toy store with very few kites, I still love to teach and I go to the International Kite Festival in Long Beach, Wash., for a week.”

He used to own a kite store in Waikiki and was involved in running a kite festival in Kapiolani Park. Relocating to Maui, known among wind sports enthusiasts for its strong winds, in 1982 “was a dream come true,” he said.

But the wind has now played a major role in the destruction of his main business, Maui Toy Works, located in the Best Western Pioneer Inn. Wind-whipped flames destroyed the historic hotel, and with it, his store. “I had $100,000 of renovations in that store,” he said. “I spent 41 years to create that dream with my wife (Barbara).”

He has a second store in the Lahaina Cannery Mall, which is still standing, but its fate is uncertain.

His first inkling of trouble also came when he lost electricity. He was outside emptying the trash when he saw some flames in the hills to the north. “I knew there were some fires up on the hill,” he said, “but it shot down into the historical district. It’s crazy.”

They immediately drove to a friend’s house in Launiupoko, a few miles south of Lahaina, but a few hours later police ordered them to evacuate again. “There was no choice,” he said. “Even though we live in Kapalua, north, we could not go home, so they sent us off with no destination. You gotta figure it out yourself. They sent us south.

“There were hundreds of cars parked along the side of the road, people sleeping there, no internet, no communication, no electricity. It was surreal.”

The Loeras eventually found housing with friends in Kahului, helping other friends evacuate from Maalaea along the way. Robert Loera knows his house has survived, but at age 67 and with 80% of his income coming from his Pioneer Inn shop, he sees his business coming to an end.

“I don’t know if I’m totally devastated, but I’m pretty devastated,” he said. “I’m out of business. I’m probably retired.

“The thing that’s really hurting is that people who work for me, most of them lived on that hill,” he said. “Two of them lost homes, but two of them didn’t,” he said. “So now all I can think about is when I get home I’m going to clean my closet out because I know there are all these families that have lost their homes and they need clothes and things.”

No power, no internet

Sharon Nakama, a music teacher at Baldwin High School, lives in Kula in Upcountry Maui. Wildfires started a few miles from her home but eventually came about a quarter mile away, close enough for her family to see flames licking the sky. They lost power at about midnight Tuesday, but she still went to work Wednesday.

“I didn’t think the fires would be so close and my parents went back home Upcountry to see the situation,” she said, “but there was another fire that started on their way home. So we got separated, but according to my dad the fire got really close at night, so you could hear some pop and crackling of the flame.”

Nakama, 29, stayed with a co-worker in Kahului and monitored the fire online via satellite imagery. “The fire surrounded the house — not really close, but kind of scarily close,” she said. “It was really scary because I had stayed downtown … because I couldn’t get home, and there was no (phone) service up there, so it was kind of guessing by looking at the mountain if the fire was near my house, and then not hearing from my parents was really scary.”

She was able to get home Thursday and found that the home had electricity but no water. “I’d rather have water than electricity,” she said.

“There was a lot of burnt debris from the wind. There was more debris on the road, blocking it, than the actual fire, so entire trees were knocked over. At King K. (King Kekaulike) High School, all the light poles and posts are on the ground flat right now, knocked over,” she said.

With the charred, blackened debris from the fire swirling around, she was reminded of “‘Hawaiian snow’ from the sugar cane days.”