Mickey Weems made a deal with the universe that as long as he had the strength to keep up his bodybuilding and go out to dance, he would not end his life — yet.

When he can no longer live on his own, Weems has arranged to die through medical assistance, as allowed under Hawaii’s Our Care, Our Choice Act for terminally ill patients. He said this brings him great comfort because being a burden and dependent on someone is his version of hell.

In the meantime, he lives in constant pain and extreme fatigue with terminal prostate cancer. After a diagnosis in April 2021 predicted he had six to 12 months to live, Weems has beaten the odds. He has refused debilitating chemotherapy and is only being treated with targeted radiation and monoclonal antibodies.

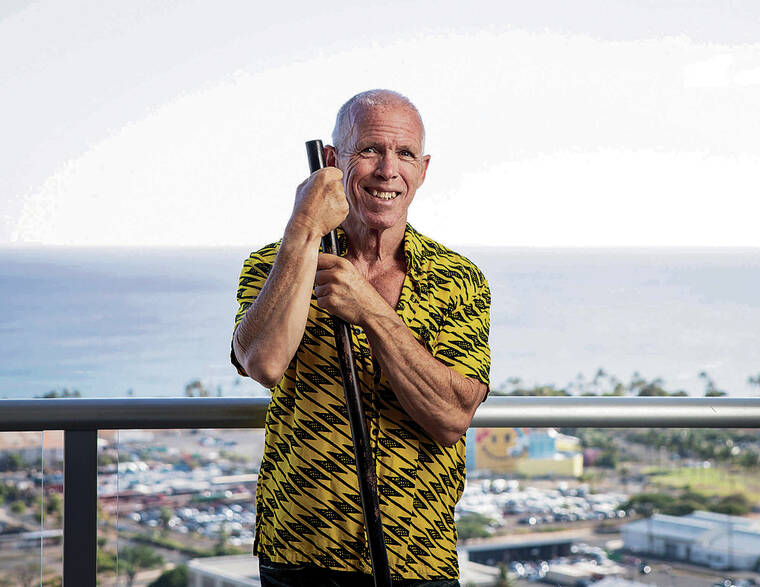

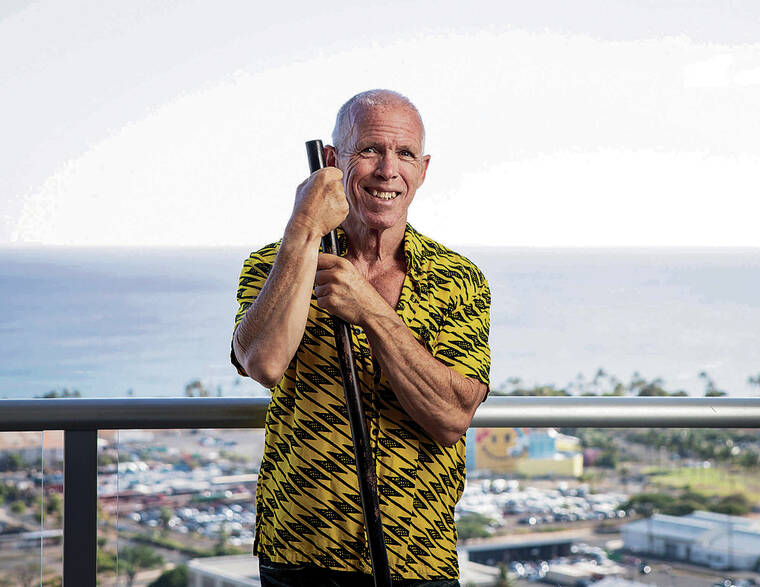

“As long as I can dance and move by my own strength, I will continue to live,” said Weems, 65.

“Vanity is keeping me alive,” he said. But what motivates him, besides self-discipline and stoicism, is the need to help others facing hardship, especially men with prostate cancer who have sunken into despair.

He began sharing how he wants to live in the face of death on Facebook, but since last July, Weems has delved deeper through a podcast called “Mickey Is Dying.” The episodes, available on Apple Podcasts and via RSS.com platforms, are produced by James Charisma and Donna Blanchard, also a co-host, as a labor of love, said Susan Wright, who donates her services as communications director. About 20 podcasts, each about 20 to 25 minutes long, have been broadcast, and another 30 recorded will be released on a weekly basis.

The interviews will be recorded as long as Weems’ health allows, and will continue to be released after his death to help as many people as possible, said Blanchard, managing director of Kumu Kahua Theatre and a former host of ThinkTech Hawaii, a web-based talk show. She had known Weems as a Facebook friend a few years before seeing his posts about cancer. After she commented on how meaningful they were, he called her and said: “I want to help people somehow; help me help people,” Blanchard recalled.

She immediately suggested a podcast, seeking help from Charisma and Wright, with whom she’s worked before. They record the episodes on Zoom from their own homes on Oahu, which makes it easier on Weems’ health. The bond that’s developed between Weems and the team is often expressed on air, so the interviews turn into poignant conversations with probing questions from Blanchard that he doesn’t shy away from: “We’re family,” Blanchard said.

In spite of their serious nature, the episodes are energized by Weems’ pithy one-liners and admitted “gift of blarney.” He is a fountain of epiphanies, delivered with the kind of bravado that belies his impending demise. The interviews have helped to define this passage of his life and bring him real comfort, along with his family and friends, he said.

Judging from the feedback, the podcasts have hit a nerve with followers, especially among men with prostate cancer who’ve contacted him in tears.

“Because prostate cancer is in your gonads, and that is such an incredible horror for a man to realize that he has lost the function of everything downstairs. You don’t want to talk about it, don’t want to mention the times when you’re out in public and all of a sudden you’ve urinated on yourself — absolutely, completely embarrassing things that can happen and that happened to me. Those are the guys I really want to reach,” he said.

His biggest fear is “that I quit. … quitting is unacceptable.” He could easily lie in bed and sleep all day, but he forces himself to stand up and move. Devoted to bodybuilding for 50 years, he works out at the gym four times a week (down from six times since May). He takes long naps to ready himself for nights out at his favorite club twice a week, as dance is sacred to him. Weems turns the walking stick he uses for support into a stylish prop while dancing.

A former university professor in Hawaii, Ohio and Georgia, Weems’ expertise in world religions, English and anthropology lend added dimension to the nuggets of wisdom he shares. His perspectives are also drawn from diversity as a gay man, a Sufi (a believer in Islamic mysticism) with strong Irish Catholic roots, an ex-Marine and a former lifeguard.

Ultimately, Weems sees himself as a philosopher in the mode of Socrates and Seneca, who took their own lives with the utmost bravery for principles they stood by, and he hopes to leave a similar legacy. He’s working on a comic book about a superhero with cancer, but it’s better explained in a book of meditations he’s also writing called “The Book of Pueo.”

“To those who find value in my words: If I could die for you, I would,” Weems writes in “The Book of Pueo.” “So it only makes sense that I would continue to live for you, despite the unrelenting pain of cancer and no matter how tempting it is to board that ship and sail on to the next world before I do more work.”

In the podcast’s first episode, Weems talked about picturing his cancer, which has spread throughout his body, in the “image of yellow lilies blooming along my spine, which comforts me.” It’s not an enemy to battle as others commonly imagine it. “People say, ‘I’m not defined by my cancer,’ but I am and I embrace it” because it’s something that originated in him, he said.

Blanchard said it’s this attitude that sets Weems apart.

“The idea that he’s accepting of it, he’s not trying to kick it out,” she said. “He at least embraces the concept that he’s doing it on his own terms, and they do not involve the heroic measures that it might take to try to eradicate it.”

She’s told him on one of the episodes: “Geez, everybody should live as well as you are dying, Mickey.” Often at the end of an interview, Blanchard doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry, but she’s always deeply moved, she said.

While his body is getting weaker with fatigue, Weems said his mind and spirit are soaring. He is not afraid of death, he said in Episode 3 of the podcast, having achieved peace of mind with the preparations to end his life.

He said he’s faced this juncture before. He almost died while lost alone at sea in 1984; while awaiting rescue, his grandmother’s spirit said to him: “Whether you live or die, you will be fine.”

“I’m so ready to go. I’ve been at that stage for a while but the universe keeps on throwing pleasures at me I didn’t know existed before,” he said. “The world is a source of wonder; it’s becoming more beautiful every day. … The universe is conspiring for me to live longer.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story used the word enervated instead of energized.