Thousands flock to Waimea Bay to watch ‘The Eddie’ surf contest

JAMM AQUINO / JAQUINO@STARADVERTISER.COM

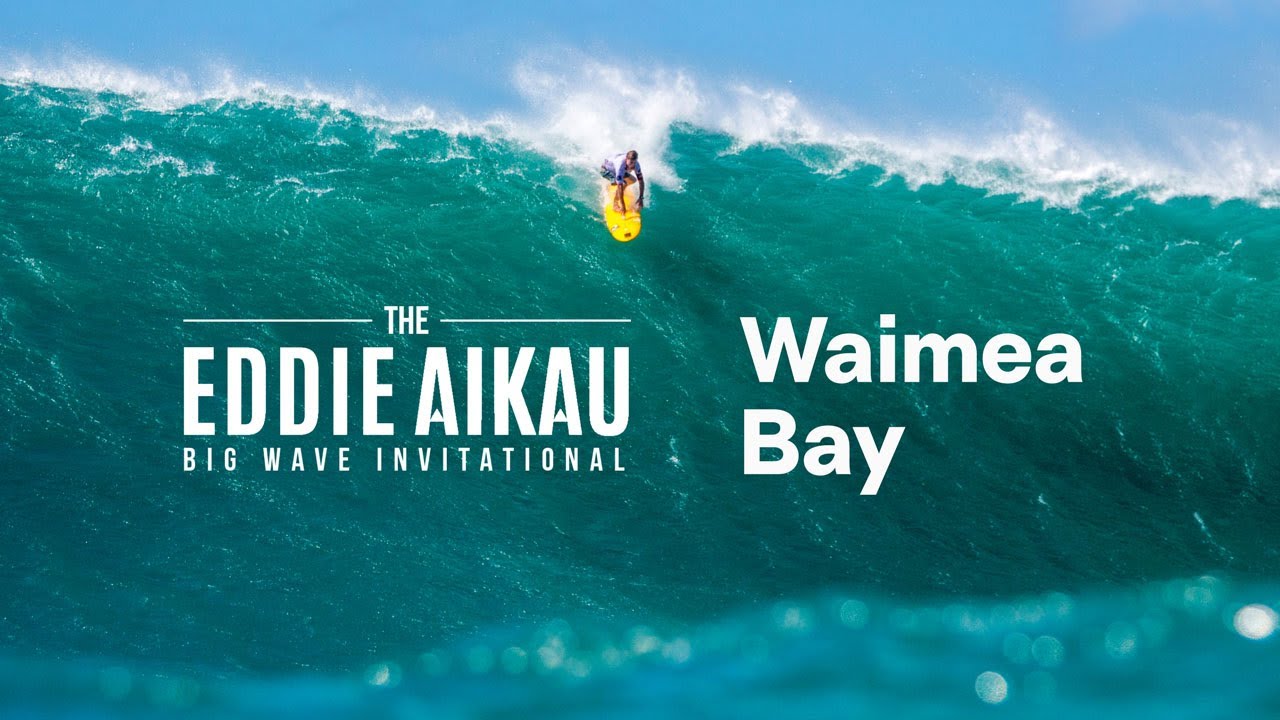

At top, Eddie Aikau Big Wave Invitational winner Luke Shepardson rode a wave Sunday during the competition at Waimea Bay.

CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARADVERTISER.COM

Above, Kamehameha Highway was packed with people and cars at 10 a.m. Sunday.

CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARADVERTISER.COM

Above, spectators packed the viewing area at Waimea Bay early Sunday morning before the start of the Eddie Aikau Big Wave Invitational.

On the morning of the Eddie Aikau Big Wave Invitational, Christa Funk woke up at 4 a.m. in Kahuku and loaded her car with her camera gear. The plan: swim for eight hours in the lineup of Waimea Bay, with closeout sets breaking around her, while she shot the world’s best big-wave surfers riding monsters.

Her husband drove her south to drop her off, past dozens of cars parked, past tents and people hauling chairs and coolers in the dark from Rocky Point all the way down to Waimea Bay. Just past the church that overlooks Waimea, people appeared in the headlights thronging the road, half a dozen deep, packing the cliff.

“I was scared and nervous,” Funk said, “and very excited.” Hawaiian Water Patrol towed her out on a Jet Ski at 7:45 a.m. and let her loose in the lineup.

The competitors parked their cars close to the beach and considered which big board to ride. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of people jockeyed for viewing positions.

Paige Alms, in her first time competing in the “Eddie,” would choose between a 9-foot-8-inch, 9-foot-10-inch or 10-foot-4-inch board, depending on the size of the waves.

Kai Lenny, also his first time in the contest, was considering a 10-foot or 8-foot-8-inch board.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

“I’ve never been a part of an event this big before,” Lenny said. He had woken up at 5 a.m., stretched and eaten an egg burrito.

Lucas “Chumbo” Chianca, a Brazilian surfer, had arrived on Oahu four days before. He had come, too, when the Eddie was called earlier in the month. His board options: a 9-foot-6-inch or a 10-foot-2-inch. “I’m super excited and honored to be invited,” Chianca said.

Greg Long, a surfer from California, was excited. “The overwhelming opinion is that the buoys are showing the swell to be way bigger than was originally anticipated,” Long said. His three boards were all 9 feet 6 inches.

In an announcement that would become a refrain throughout the day, a lifeguard warned the crowd on the beach over the intercom, “Ladies and gentlemen, this wave is coming up through the crowd,” he said. “Grab all your stuff.”

The waves averaged 25 feet Hawaiian (50-foot faces) throughout the event.

As the light came up, spectators hung in hammocks from trees and the rock-retention fence along the cliff. The light shot through the valley and fell on the churning white foam as it approached. People took up nooks in the rocks and on the rocks, some too close to the water. An ambulance arrived after a boy fell out of a tree. The shorebreak rushed up the beach and flooded the river mouth. Legs hung from the rocks to the south; tents and crowds packed in where they could, turning the bay into a coliseum. Overhead flew a half-dozen drones and someone in a yellow ultralight.

“The Eddie broke Surfline!” a man working for the forecasting website, which was producing and streaming the event, said aloud.

After surfer Mark Healey returned from his heat, he declared, “I don’t have a theory for the sets.” The bay was closing out across its width.

Grace Thacker, 33, woke up at 3:50 a.m., borrowed her brother’s truck and drove up from Manoa. She sat on the roof of a production company’s van, glimpsing the surf between the trees. “I’m loving the dynamic between good vibe and crowd control,” she said. “I love listening to the lifeguards.”

“Get ready to get sprayed,” someone on the intercom said to the crowd as the white water rushed up the beach. “It can actually rip your arm and leg out of your sockets,” he said.

On the north slope of the bay, a crowd sat down on the rocks right where the whitewash came up, occasionally taking some spray. The lifeguards called back a man who was trying to get lower to the waterline. “Don’t embarrass our section,” a woman shouted.

A surfer was riding a wave all the way in to the shorebreak. “Pump it!” yelled a shirtless man as the crowd cheered.

Ugo Corte, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Stavanger in Norway and the author of “Dangerous Fun: The Social Lives of Big Wave Surfers,” described the Eddie as a “religious ritual.” “No different from a Catholic ceremony, maybe more powerful,” he said.

The contest, in his view, also has a “binding” effect on both the surfers, who entrust themselves to each other in the face of watery death, and their community.

Corte, who conducted his ethnography of big-wave surfers on the North Shore over the past decade, stood beneath the lifeguard tower in a pink button-up shirt, watching his subjects ride waves. “We’re constantly scattered, we’re constantly in a rush,” he said. “Everybody’s pressed for time and these things slow down time,” he said. “The fact that it’s so rare adds sacrality to the event.”

“I’m still digesting the day,” Ian Walsh said after competing. “There were definitely good waves with good entries,” he said, but it had been “lully.”

“It’s the most consistent Eddie I’ve ever seen,” said Dennis Pang, a North Shore shaper for more than four decades. “Like 1990,” he said.

The surf had blasted sand and water across Kamehameha Highway. The Ke Nui bike path, in places, was inundated and sandy. The beach extended into Ehukai Beach Park’s parking lot. Pipeline, looking like rolling hills, was unrecognizable.

By the end of the day, Chianca had six stitches in his calf after his fin sliced it open in the shorebreak. Funk, the water photographer who had been swimming all day, had a high- contrast sunburn around her throat. “I need to drink a lot of water,” she said.

The surfers with the best eight scores gathered to hear Clyde Aikau, Eddie’s brother, announce the winners. The prizes: a thousand dollars here, another few there, and many thousands of Hawaiian Airlines miles.

“I love that the biggest contest in surfing has the smallest prizes ever,” said Ian Akahi Masterson, who helped organize the event, as Clyde Aikau called out the names. “Because it really comes down to the bragging rights,” he said.

Luke Shepardson, a 27-year-old Waimea Bay lifeguard, won the event. “I’m tripping,” he said. “I’m still on duty.”

Shepardson, who was born and raised on the North Shore, said this isn’t the start of his competitive career. “This is the only contest that I’ll probably ever be in,” he said, despite having made an earlier go of the contest scene years ago. “I surf for myself, for fun,” he said.

On beating John John Florence, a one-time Eddie winner and two-time world champion, Shepardson was baffled: “He’s the best surfer in the world, and I can’t believe I beat him.”

How the Eddie got called came down to the clairvoyance of Pat Caldwell, who retired from a 33-year career as an ocean data liaison with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Caldwell, a 62-year-old lifelong surfer in camo board shorts with straight graying hair down to his shoulders, has a legend that precedes him; some say Surfline has changed its swell forecast when his has differed.

Caldwell began tracking weather models for this Eddie about 10 days before. “You have to take anything beyond 10 days with a big grain of salt,” he said. The best models weren’t showing enough size, but the Navy’s model, what Caldwell called the “least reliable,” predicted that an Eddie swell would hit Sunday.

The conditions for an Eddie have to be just right, according to sheets of swell data of every Eddie since 1986 that Caldwell held in a manila folder. “You need the head of the generating winds about a thousand nautical miles away,” Caldwell said. The storm that brought this Eddie swell began stirring 40- to 47-foot seas about 1,000 nautical miles away on Friday evening. The long-period swell — 20 seconds, for those who care — travels 700 nautical miles a day, he said.

At 2 a.m. Sunday, Caldwell checked a buoy northwest of Kauai. It was 270 nautical miles from Waimea, an eight-hour trip for that swell. He consulted his historical data and saw a striking similarity to an Eddie of two decades ago.

“I went and dug up all the weather charts from the 2002 cases,” Caldwell said, “and I found the estimates of the waves out in the ocean and the track of the low-pressure system was almost identical to the one in the model for this event,” he said. “Because we had such a twin, it gave confidence that even though our best models are saying it’s not going to be Eddie, here’s a similar case where it was an Eddie,” he said. Thirty-foot Hawaiian swells hit the bay in 2002, and Kelly Slater won the contest.

“It was identical to this,” Caldwell said. “Clear skies, absolutely identical for the local weather.” By his estimation, the sets put up 48-foot faces. “But no one’s out there with a tape measure,” he said.

Although the contest had ended, the crowd continued to bellow as surfers dropped in on waves.

A lifeguard piped in with a megaphone: “Yeah, guys down by the river mouth, you might want to back up. This contest is over but the swell is not.”

A set was coming in.

“That’s a twenty-fiver there,” Caldwell said.

“Yeah, guys, back up,” the lifeguard said. “You should be able to see a 25-foot, giant set approaching,” he said.

“Hey, I’m glad I agree with the lifeguards,” Caldwell said.