Dave Reardon: Jack Scaff / 1935-2022 — Cardiologist and Honolulu Marathon founder brought event to the masses

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / 2021

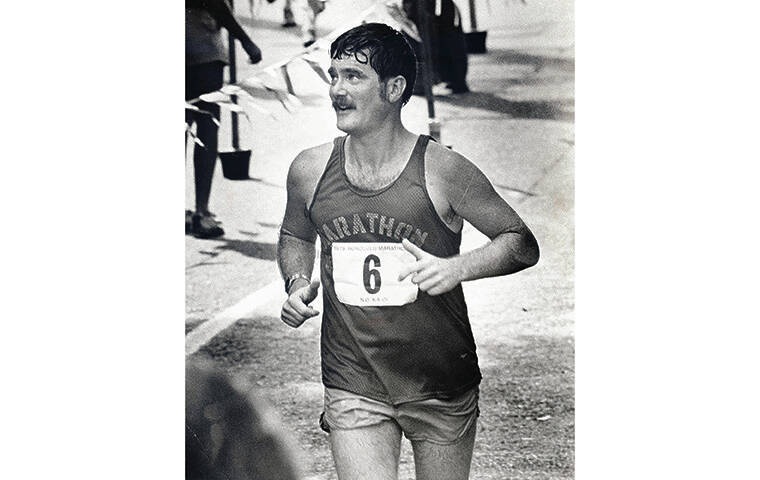

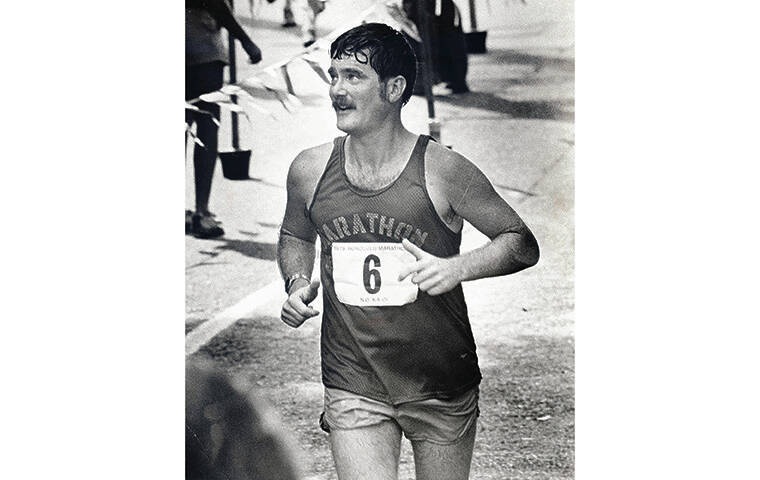

Scaff, above, ran the Honolulu Marathon in 1978.

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / 2021

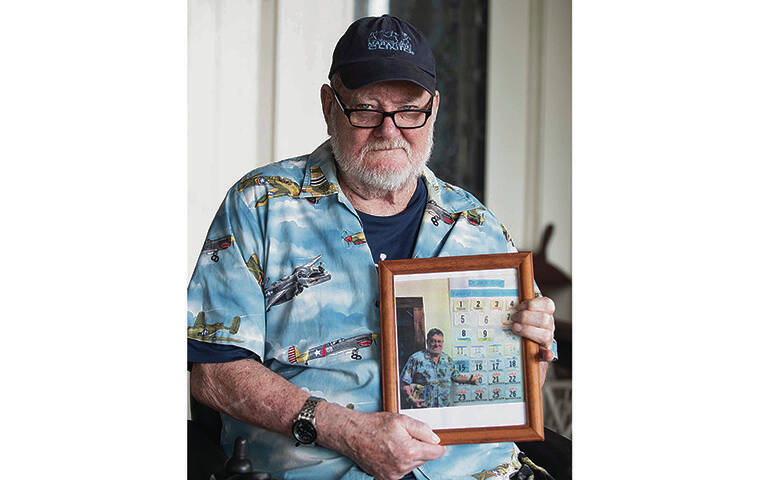

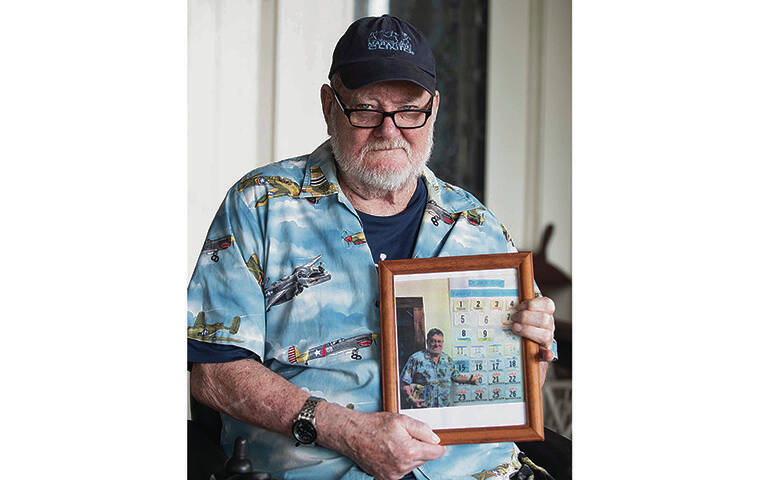

Honolulu Marathon founder Jack Scaff held a photograph of himself with his entry numbers, 1-26, for each year he ran the marathon since 1973.

STAR-ADVERTISER / 2021

Jack Scaff:

Started the “People’s Race” in 1973

Before Jack Scaff, distance running was considered a very lonely and not necessarily healthy endeavor.

Marathoners were thought to be either superhuman or crazy. Or both.

But Scaff, a cardiologist and founder of the Honolulu Marathon, improved and extended lives by encouraging all kinds of people — even heart attack victims — to train for and complete the 26.2-mile run previously reserved mostly for elite athletes.

Scaff, 87, died peacefully Monday at his home in Makiki after a long illness.

The Honolulu Marathon, which Scaff started in 1973, lives on, as does the Honolulu Marathon Clinic that he also founded.

“I think it was cutting edge,” said his son Jack Scaff III. “He’s the first physician in the country to have a (patient who was a) heart-attack survivor complete a marathon.”

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

One of his first post-heart-attack patients was also an airline pilot, whom the FAA re-certified after he completed a marathon.

“Before he started the cardiac rehabilitation program, people were told lots of bed rest was the best way to recover,” the younger Scaff said. “He wanted them to get up and start exercising.”

Dr. Scaff was in the right place and at the right time — at the cusp of the running boom of the 1970s. Before then, few considered distance running as something to do for recreation or fitness.

“Marathoning was thought of as a sport for the elite. Those weren’t the people my dad catered to,” his son said. “He always was the person who supported the back-of-the-packers.”

Although not necessarily by design, that philosophy helped make the Honolulu Marathon a huge business success.

“It’s the masses who spend money,” Scaff III said. “The elites take the prize money.”

The combination of research by Scaff and others proved the physical restoration value of distance running. That, and his personal philosophy of inclusiveness, earned the Honolulu Marathon the tagline it still has today, “The People’s Race.”

Unlike other marathons, Honolulu has no time limit for entrants to complete the course.

And, although they didn’t yet sign up by the thousands as they do now, in 1981, Scaff’s last year as Honolulu Marathon president, his connections started what evolved into an annual gusher flow of entrants from Japan.

The Honolulu Marathon Clinic is as much, if not more, telling of Scaff’s impact and legacy than the race itself.

Backed by medical research, Scaff and other experienced runners encouraged beginners, advising them on how to get started and remain motivated through the months of training they would need to attain the previously unthinkable goal of completing a marathon.

Some of the advice was as simple as if you couldn’t speak clearly while jogging you might be going too fast; the importance of training with others was almost a given.

As a former football player, Scaff knew the value of teamwork. Through the marathon clinic he’d figured out how to make it a component of one of the most individual sports of all.

“The clinic represents something of a lifestyle,” Scaff told Michael Tsai in a 2021 Honolulu Star-Advertiser story. “People who run like to run with one another.”

Even the most grueling activities can be fun when endured with others.

“You talk about the social aspect,” Scaff family friend Wes Nakama said. “I know couples that met (at the marathon clinic) and married.”

Although opinionated and considered brash by many, Scaff was also charismatic enough to attract the key players to build the marathon’s operational foundation. Now, thousands take as much pride in volunteering to work the marathon as those who enter the event.

Scaff started the Honolulu Marathon with support from then-Mayor Frank Fasi, Olympic weightlifting legend Tommy Kono (who then worked for the city’s Parks and Recreation department), and others, mostly volunteers.

One of Scaff’s innovations was aid stations set up every few miles, where marathoners could get cups of water or other liquids.

For Scaff himself, at one marathon “other liquids” meant beer.

“He ran a whole marathon just drinking beer,” said Tsai, author of “The People’s Race Inc.: Behind the Scenes at the Honolulu Marathon.” “He was trying to prove that here’s this high-caloric, high-carb drink that short term will keep you hydrated enough to run 26.2 miles.”

That’s my kind of research; my personal Jack Scaff story also involves beer. I was 16, it was 5:30 a.m. and I was on a bus somewhere downtown, sipping from a can in a brown paper bag.

He was my dad’s cardiologist, and because Scaff wrote or said somewhere that drinking a beer before a long run was a good idea, I attained parental permission to do so before my first Honolulu Marathon, in 1977. I don’t know if it was because of the hops and barley, but I did manage to complete the 26.2 miles.

“He was obviously a proponent of beer,” Nakama said. “He had a keg a week delivered to his house. He was a cardiologist, and a very good one. But probably the only one whose favorite hobby was hosting and going to chili cookoffs.”

Driven and passionate about causes, Scaff also was clearly a bon vivant — or, as he’d surely prefer, a guy who loved making friends and hanging out with them.

“My dad could be no-nonsense and to the point,” Jack Scaff III said. “Deep down he was a gentle, caring man that wanted to make a difference in the world with everything he did.”

Jack Scaff Jr., was born in New York and raised in New Jersey. He graduated from the University of Medicine And Dentistry of New Jersey (Newark). He served in the Peace Corps before moving to Hawaii.

His many honors include being the first Hawaii resident to be named a fellow of the America College of Sports Medicine, the first inductee into the Honolulu Marathon Hall of Fame and a member of the Hawaii Sports Hall of Fame. He was also a founder of the Great Aloha Run and other running events.

He is survived by his wife, Donna; sons Jack III (Julie) and Kawika; granddaughters Margaret and Emma; brother, Walter; and sister, Anne. Services are pending.