Agricultural theft costing Hawaii farmers

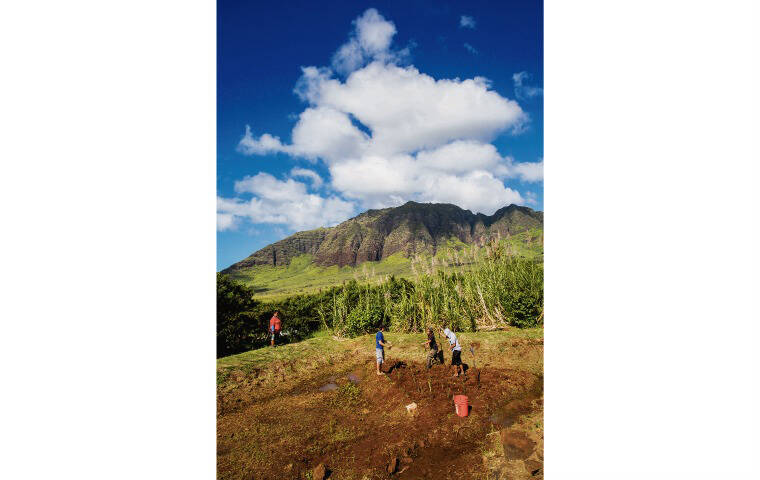

STAR-ADVERTISER / 2018

Kaala Farm staff assist students from Nanakuli High School in the farm’s kalo fields. The farm reported the theft of their fencing and asked the community for help in catching the thief.

Agricultural theft continues to wreak havoc for many farmers in Hawaii.

For example, three alleged thieves were arrested for a June 9 incident and charged with stealing 200 pounds of lychee from OK Farms in Hilo. On June 26 two people, one of whom was among the OK Farms suspects, were arrested for stealing $260 worth of tropical evergreen mangosteen fruit from Sunshine Farms in nearby Papaikou.

And on Oahu on July 1, about $10,000 worth of special fencing to help prevent dry-vegetation fires was stolen in the night from Kaala Farm in Waianae.

The recent incidents represent just a snapshot of a chronic issue for Hawaii farmers.

“Every year we have ag theft, and every single year they get away. And this was one of the first years they got caught,” said Kea Keolanui, spokesperson for OK Farms and the daughter of the farm owner.

Many Hawaii farmers operate on slim profit margins and face numerous challenges to grow their operations. Difficulties accessing land and labor as well as high production and shipping costs are among the most well-known, but agricultural crimes are also a common complaint.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

While incidents are often not reported to police, about 14% of the state’s farms did report some kind of agricultural crime in 2019, including about 25% on Oahu and 15% on Hawaii island, according to a 2020 publication by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and state Department of Agriculture based on surveys of Hawaii farmers.

Eric Enos, co-founder of Kaala Farm, said the stolen panels were from a fence still under construction. The 1.5-mile fencing was supposed to connect to a fence at the Waianae Kai Forest Preserve.

“It was almost done. We contracted a local contractor. … That morning, it was almost finished, and he said, ‘Hey, a whole section of your fence is just gone,’” Enos said. The fencing would help the farm raise sheep, which eat dry grass and prevent the spread of wildfires. Enos said the effort was prompted by the 2018 wildfires in Waianae and Makaha that ended up burning some 9,000 acres of land.

The thieves have yet to be caught, and the stolen panels haven’t been recovered.

The total cost and losses from agricultural crimes in Hawaii in 2018, according to the USDA publication, was an estimated $14.4 million, or 10% of that year’s total estimated net farm income in Hawaii. Theft of farm commodities, property and equipment accounted for about $2.6 million in costs for Hawaii farms that year, and vandalism added about another $500,000. Most of the costs — about $11.2 million — came from security costs to prevent theft and vandalism.

Despite those security costs, which include the installation of cameras and alarms, prevention remains difficult. Even when suspects are caught, a prohibitive amount of evidence is often required to successfully prosecute them.

“It’s hard to prosecute … because law enforcement is so busy, and by the time they come the people are gone, or you can’t identify these guys,” said Randy Cabral, president of the Hawaii Farm Bureau Federation. “And you’ve got to prove that they took from your farm.”

Agricultural crime losses, as a result, are often viewed as a cost of doing business.

A state DOA program in 2020 funded by the state Legislature found that a “major problem” with agricultural crimes is that farmers aren’t reporting them.

The program, which focused on Hawaii island and examined the effectiveness of agricultural crime prosecution, described a sense of hopelessness amongst farmers when it comes to crime.

“… (T)here is a possibility that victims are given the impression that the crime lacks importance by law enforcement, such as when the responding officer takes a report but does not report back to the victim thereafter,” the report said.

But going forward, the report said, there needs to be collaboration between farmers and local law enforcement agencies to prevent crimes, and both should have a better understanding of how the other operates.

Many say the enforcement of existing laws could help keep agricultural theft down.

In Hawaii, anyone who sells agricultural commodities weighing more than 200 pounds or have a value of more than $100 is required to have an ownership and movement certificate, which can establish a paper trail for produce.

But those forms are not always checked by businesses.

“Regular enforcement of form use would reduce sales of stolen produce to wholesalers, restaurants, and supermarkets,” the report said. “Businesses that do not use the form are reportedly the easiest places to sell stolen produce.”

Farmers markets and roadside sellers also provide markets for stolen farm goods, Keolanui said.

“If there wasn’t a market for (stolen goods) … the problem would be lesser,” she said. “The problem would be people stealing for their own use, like taking lychee and taking produce because they’re hungry and they need food. That kind of theft will always be here … but it’s not the big problem.”

In the meantime, both OK Farms and Kaala Farm have appealed to the community to help with the issue.

Kaala Farm reported the theft of its fencing on its Instagram account, which has more than 2,200 followers. Later that day, it received and posted a video of a pickup truck with what appeared to be the stolen panels.

“That’s why we did the social media thing and blasted it out, and that’s when we got the footage,” Enos said.

Keolanui said she was motivated to report the lychee theft to make an example of the thieves and hopefully encourage farmers and consumers alike to demand to know the legitimacy of their food.

“That’s the bottom line — knowing where your food is coming from,” Keolanui said. “If your farmers market vendor tells you, ‘I don’t know,’ do you really want to buy from them?”