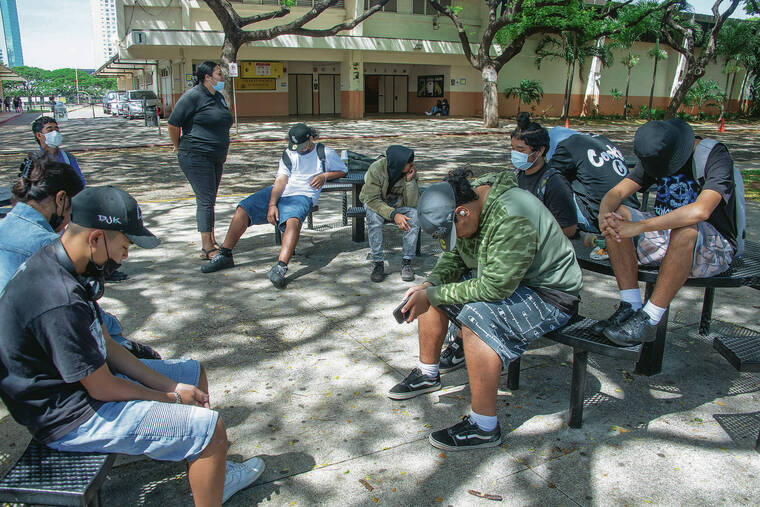

Siwian Nickepwi, 17, closed her eyes and went to a dark place Wednesday during a calming activity for Adult Friends for Youth, an organization that redirects high-risk youngsters.

“It’s midnight. It’s cold,” Nickepwi told Titi Takai, who is leading AFY’s in-school counseling group at President William McKinley High School, more commonly referred to as McKinley High School. “But then I pictured those that we’ve lost, their laughs echoing.”

Nickepwi’s vision is representative of AFY, whose mission since 1986 has been to give youth hope in the darkest times. She said kids need “a dad figure or a mom figure — a person to be there when you don’t have anybody.”

That is why the fatal shooting a little over a year ago of Malakai Maumalanga, AFY’s director of redirectional services and popular mentor, was the nonprofit’s bleakest moment. But it also gave AFY an opportunity to use Maumalanga’s story to prove that pushing beyond the pain of the past can build a better future.

Known as Mo, Maumalanga was a teenage member of the Cross Sun gang, which normalized harassing others, street fighting, drive-by shootings and organized crimes. As an adult he turned his life around and worked as the face of AFY to ensure that other high-risk youth didn’t make the same mistakes.

Maumalanga was shot to death at his multigenerational Aiea home at 9:45 p.m. March 27, 2021, just 10 days after his 45th birthday. He was found lifeless in the carport of his home with multiple gunshot wounds to his upper body.

The crime, which police classified as a second-degree murder, is still unsolved.

Honolulu Police Department spokesperson Michelle Yu said, “This case remains an open investigation. No arrest has been made. Anyone with information should contact HPD or CrimeStoppers.”

Despite the lack of progress in the investigation, the nonprofit AFY, which operates like a family, has found a way forward for the troubled kids whom Maumalanga counseled and a growing stream of new kids with pandemic-exacerbated problems.

Deborah Spencer-Chun, AFY’s president and CEO, said the death of Maumalanga, whom she regarded as a son, left a void at AFY. But she said his death also has inspired staff to set the bar high in Maumalanga’s honor — realizing that each client could also be someone who is capable of possibilities that defy the limits of where they came from.

Spencer-Chun counseled Maumalanga when he was a teenager, standing by him after he was arrested at 18 in connection with a gang- related drive-by shooting. Maumalanga wasn’t convicted of the shooting, but went to prison on a weapon charge.

When he got out, Spencer- Chun invited Maumalanaga to live with her family. She also encouraged him to earn bachelor’s and master’s degrees in social work and to work for AFY.

Spencer-Chun still recalls a pivotal moment in Maumalanga’s transition when she asked him,“Where do we go from here?”

It’s a question Spencer- Chun said Maumalanga used frequently in his own work with troubled youth. It is also a question that she has asked herself and AFY since Maumalanga’s death.

In the end, Spencer-Chun said, it comes down to love, which is how AFY motivated Maumalanga to build a new life.

“Mo had gotten in so much trouble that he was enrolled in almost every school from Kalani to Waipahu. At one point the family took him back to Tonga,” she said. “When he returned he struggled with people labeling him. He was angry. He didn’t feel love. The love was the part that we were trying to pull out of him. We knew he had it in him.”

Love is the glue that has kept AFY’s tightknit group of employees coming to work despite their loss. They’ve found strength in the pain and are digging deep to stop violence, keep kids in school and address the negative impacts of the pandemic’s social and economic disruptions.

“We have to connect kids back to their heart,” Spencer- Chun said. “The pandemic has made a lot of kids angry. The angrier that they get, the harder that we have to work.”

Mufi Hannemann, president and CEO of the Hawaii Lodging & Tourism Association, said AFY is expected to be one of the district’s social services partners as soon as the “Weed and Seed” law enforcement program comes to Waikiki.

Hannemann plans to revisit helping AFY get office space in Waikiki so that it can prevent crime by bringing on-the-spot counseling services to troubled youth. Spencer-Chun also is raising money for a mobile outreach van, which AFY plans to dub “The Mo,” so that kids can get services in their own communities.

“Their biggest challenge is going to be funding,” he said. “HLTA has tried to help AFY through the annual Visitor Industry Charity Walk, but they could use more government funding and the like.”

Hannemann said Maumalanga’s firsthand knowledge and credibility earned him the respect of the Visitor Public Safety Coalition. They were grateful when Maumalanga marshaled AFY resources to help reduce youth violence in Waikiki, he said.

“Unfortunately, Mo passed away, but he is providing a lot of motivation for those that remain behind,” Hannemann said. “They are still at the top of their game, and we cannot do ‘Weed and Seed’ in Waikiki without them. AFY can look kids right in the the eye and say, ‘You can’t fool me. There’s a better way. There’s a better life out there. Let’s turn this around.’”

Making Hawaii safer and creating more opportunities for kids motivates Maumalanga’s widow, Lisa Tamashiro Maumalanga, to continue the work that they did together. She met her husband at the nonprofit, where they worked together for 11 years.

“I know that a lot of people still ask what’s going on with the investigation,” Tamashiro Maumalanga said. “For me personally, I don’t really think about what happened.

“I know for some they just want justice or whatever they want to call it. But it’s not about that,”she said. “It’s about who he was as a person and what he gave to the world. How do we honor that part of it? The answer is through love and kindness.”

Tamashiro Maumalanga said she and the children whom she shared with Maumalanga have found a safe place to heal at AFY. When the emotions get too raw, she escapes into Maumalanga’s former office, where his presence is still felt.

There is a rack in his office where the clothes that he shared with kids who had job and school interviews still hang. On the door are pictures and notes that Mo received from former clients whose lives were cut short. A memorial with a picture featuring his ready smile hangs on the wall fronting the office entrance.

“The kids are really protective of this space. We are turning his office into a staff activities room so we can all use it,” Tamashiro Maumalanga said.

Jacob Iose, a 16-year-old in AFY’s McKinley High counseling group, said he likes visiting Maumalanga’s office. Iose said those visits connect him to the fun that he and other kids had with Maumalanga, who would take them to places like the beach, restaurants and the bowling alley.

“We would tease him about his bald head,” said Iose, who enjoyed the lighthearted banter but appreciated the chance to tackle difficulties, too.

He is still grateful for Maumalanga’s help in securing Section 8 housing for his brother.

“When my brother was on the streets, I would worry if I was going to see him tomorrow,” Iose said. “Now I know they got a house, and I don’t worry. That was a big thing.”

Ekibo Lucky, a 15-year-old member of AFY’s McKinley High counseling group, said he won’t forget the solid advice that Maumalanga passed down to him.

“He told us to stay out of Waikiki on Halloween. He kept us off the streets,” Lucky said. “We’d have outings, and he’d tell us what’s right and what’s wrong.”

Freddy Shomour, a 17-year- old in AFY’s McKinley High counseling group, said Maumalanga helped him become more confident so that he could overcome his “antisocial” moods.

“He would tell me, ‘Don’t think about it, just do it,’” Shomour said.

Maumalanga’s influence extended to kids across the island, said AFY redirectional specialist Jackie Espejo, who has taken over his former Kaimuki High School and Farrington High School counseling groups.

She’s particularly proud that the Farrington High Group, which comprised 10 seniors at the time of Maumalanga’s shooting, all graduated.

“They actually used what had happened to him as their motivators because they wanted to make him proud,” Espejo said. “They even took their graduation pictures at Mo’s grave.”

Nickepwi said that she has visited Maumalanga’s grave, too.

“I told him whatever was going on in my mind at that moment,” she said. “I was able to share what I was going through still.”

The pressure is on for Nickepwi, who must get good grades since she has set her sights on becoming an attorney. When she struggles she turns to Takai, who is now in her cousin Maumalanga’s former role as AFY’s director of redirectional services.

It’s not the way that Takai would have wanted to get promoted, but she said that she is grateful to Maumalanga for preparing her.

“He was in my life a long time. He used to watch me while my parents were working. I remember when I would get dropped off at his house, he would say, ‘If you’re hungry, you can go make something for yourself,’” Takai said.

Despite his tough-love mentality, Takai said Maumalanga never missed an opportunity to say, “You can do it.”

Because of what he taught her, she knows that she can rise above her grief.

“We’ve continued to help the kids that we service be better individuals like Mo would have wanted — to give them an opportunity and a chance,” she said. “Seeing that they don’t give up pushes me to continue to challenge them to reach their full potential. They can have a bright future. We’ll get there one step at a time.”

HELP AFY BY PURCHASING ‘THE MO’

Adult Friends for Youth wants to purchase a mobile outreach vehicle, nicknamed “The Mo,” which would serve as a mobile center to conduct street outreach to help rebuild the lives of high-risk youth and create safer schools and communities.

The Mo is named for the late Malakai “Mo” Maumalanga, AFY’s director of redirectional services, who was slain at his home on March 27, 2021.

It would be equipped with technology such as laptops, iPads and Wi-Fi, as well as office supplies that are crucial to completing educational assignments.

AFY says that without street outreach, many youth would fall through the cracks and into the devastating cycle of juvenile to adult incarceration.

Donate at afyhawaii.networkforgood.com/projects/137668-the-mo-mobile-outreach Opens in a new tab.