When a couple of classmates visited from the mainland in February, Honolulu attorney Bill Saunders, 69, hosted a small reunion, playing and singing tunes from the 1960s and ’70s with old friends on guitars.

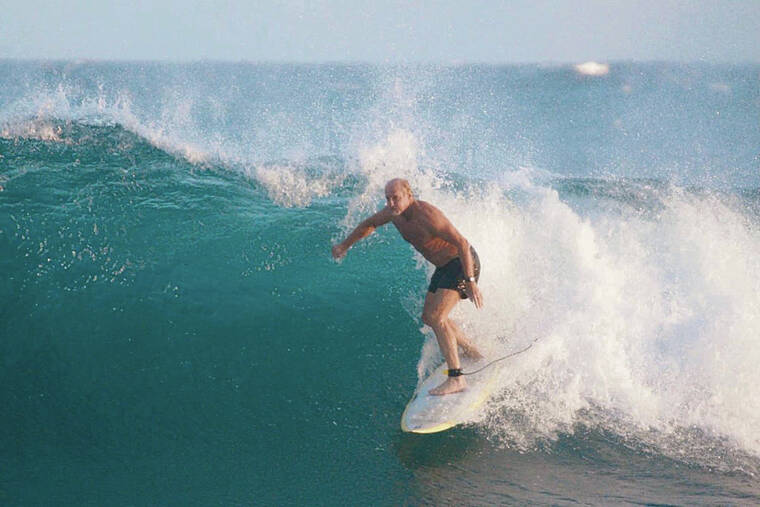

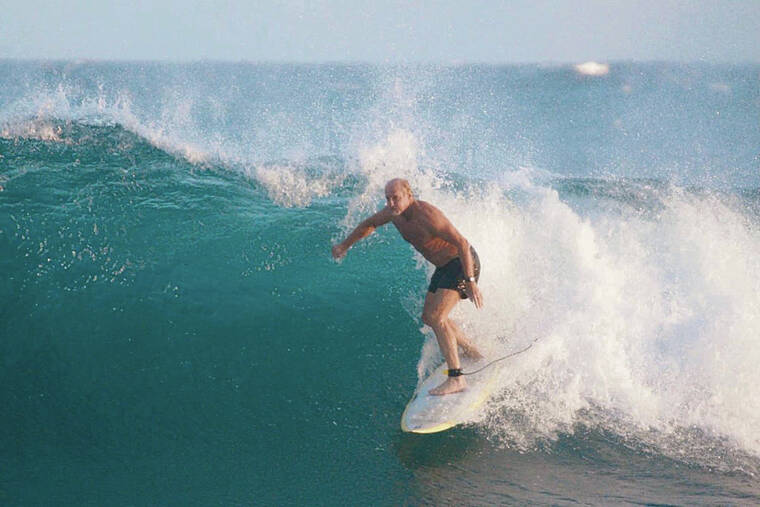

“Now that I have only a few months left before I enter early middle age,” he said with a grin, he finds playing and recording music with his friends and children, daily vigorous exercise — preferably surfing — and getting out in nature keep him nimble.

Leading a visitor up the steep brick steps from his driveway to the courtyard of his modest but multilevel Black Point house, built in 1929, “I’ve lived here since I was 11, but there are stairs everywhere,” Saunders said with a laugh, “and I wonder what I’ll do when I’m really old!”

However, he was resolved “not to let an old mindset creep in.”

To stay active and strong, he advised, “Don’t think, ‘I’m old, so I have to act differently.’”

Instead, whether taking the stairs, getting up from a chair or catching a wave, “try to keep doing things the way you used to,” he said, rather than hesitating or reaching for support.

The key word is try, for Saunders does adjust when necessary: An injury in 2021 kept him from surfing, which he recently resumed after months of rehab.

He was devastated when worn-out knee cartilage forced him to stop running, but he bicycles and walks instead, while hoping that advances in stem cell research will soon allow him to grow back his cartilage.

A lifetime of outdoor sports has taken its toll on his fair skin, so the Honolulu native can surf only when UV rays are weakest, after 5 p.m. — but he makes the most of every minute.

And although he’s winding down his sole-proprietor practice of environmental law, he is still engaged in a few public-interest cases on a pro bono basis, including an ongoing court settlement mandating public parking and safer pedestrian crossings at popular Laniakea Beach on Oahu’s North Shore.

A surfer since he was 7 years old, Saunders at age 12 joined the groundbreaking environmental group Save Our Surf, founded by Black Point neighbor John Kelly.

“I helped him map surfing sites from Aina Haina to just past the Natatorium,” he said, “including all the little spots, like Graveyards and the Winch.”

After graduating from Punahou in 1970, Saunders attended the University of California, Santa Barbara, which combined top academics with a campus on a prime surfing beach, until he was drafted.

A conscientious objector, he returned to Honolulu to do alternative service working for Planned Parenthood as a driver and clerk; he later graduated from the University of Hawaii at Manoa and Stanford Law School.

In the mid-1970s, Save Our Surf demonstrations at the state Capitol helped spur passage of Hawaii’s Coastal Zone Management/ Shoreline Protection Act.

The law allows for a private cause of action that he has used many times in representing community organizations and individual citizens seeking to preserve public access to beaches.

Also in the ’70s, Save Our Surf and others rallied to defeat the planned expansion of reef runways at Honolulu International Airport that would have destroyed surf spots and ecosystems, and evicted Hawaiian families from Mokauea Island in Keehi Lagoon.

“That’s what made me go to law school,” he said.

Saunders currently volunteers as vice president of Kokua Market Natural Foods, a cooperative he co-founded 50 years ago.

“I eat healthy,” he said, “no junk food or beef — except for the teri beef at Diamond Head Grill.”

While he said he’s never been competitive apart from a stint in Little League, he admitted he has won 11 trophies in the Land Sharks, a local legal professionals’ surf contest he co-founded in the late ’80s; he also competed successfully in a national lawyers’ surf meet at Waikiki during an American Bar Association convention in 2005.

“I won both the shortboard and longboard categories for over-30 men,” he said, his blue eyes shining. “It was unusually big at Queens Surf, and the waves were good.”

Although he has ridden big waves at Makaha and Waimea Bay, Saunders said big surf makes him “super nervous,” which he attributes to having nearly drowned in a swimming pool when he was a 2-year-old: “I jumped off the diving board and just sank.”

His children provide treasured opportunities to stay active: sea kayaking off Kauai and taking surf trips to Samoa and Indonesia with son Koa, 31; hiking, camping, skiing and snowboarding with daughter, Lani, 22, and son Jackson, 19.

Saunders watches no television except for surf events, preferring to observe Hawaii’s birds, sea life, ocean and sky.

He encourages that everyone “seek out and connect with wilderness,” as “there aren’t many real things left in this world.”

His main advice for staying youthful? Play.

“Basically, look at a toddler,” he said. “What’s their job? To learn.”

Like toddlers, he said, older people should be curious and resilient, play and laugh with abandon, and pay attention to their feelings, which adults too often repress.

“Be consciously young at heart,” Saunders said. “Otherwise, you’ll be just plain old.”