Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin has ordered the Navy’s Red Hill fuel facility to be drained and permanently shut down, saying in a statement Monday that it’s “the right thing to do” to advance the nation’s strategic interests and ensure the military is being a good steward of the land it occupies around Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam.

The decision marks a sudden about-face for the military. For years the Navy argued that its Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility was vital to the country’s security in the Indo-Pacific region as it pushed back against calls from the Honolulu Board of Water Supply and Hawaii Sierra Club to relocate its aging, underground fuel tanks away from an important drinking water source for Oahu. But in a statement about his decision, Austin suggested that the facility was obsolete after all and that distributing the fuel reserves would be better aligned with the needs of the military.

“Centrally located bulk fuel storage of this magnitude likely made sense in 1943, when Red Hill was built,” Austin said in a news release. “But it makes a lot less sense now. The distributed and dynamic nature of our force posture in the Indo-Pacific, the sophisticated threats we face, and the technology available to us demand an equally advanced and resilient fueling capability. To a large degree, we already avail ourselves of dispersed fueling at sea and ashore, permanent and rotational. We will now expand and accelerate that strategic distribution.”

Austin said that he made the decision after close consultation with senior civilian and military leaders and a review of fuel reserves in the Pacific theater. He has directed the secretary of the Navy and the director of the Defense Logistics Agency to submit a plan to him, with milestones, to defuel the facility by May 31. Defueling is expected to begin as soon as possible, after it’s determined that the transfers can be done safely.

Austin said that the work of defueling the tanks should be completed within 12 months.

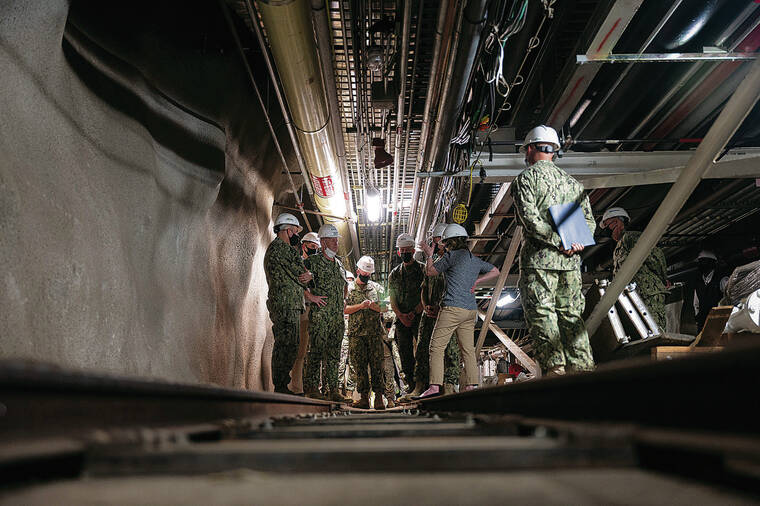

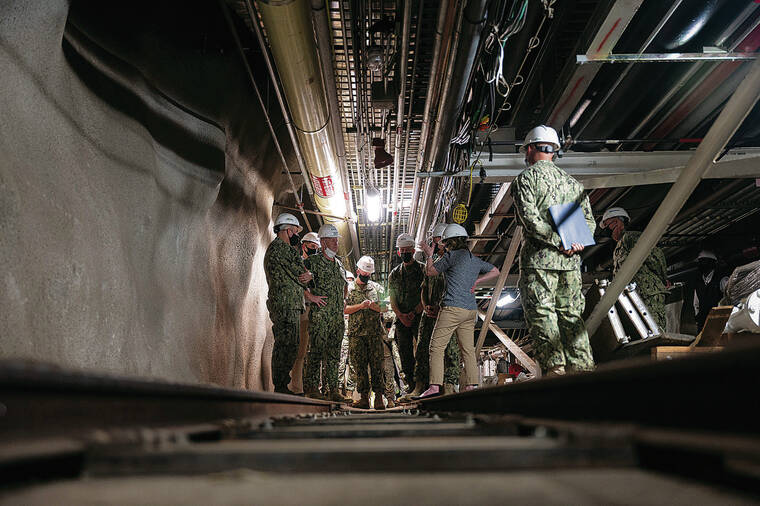

The tank farm includes 18 active underground tanks, each big enough to envelop Aloha Tower. At any given time, the Navy has said, the facility holds about 180 million gallons of fuel.

Austin’s decision comes amid a groundswell of anger toward the military in Hawaii and growing calls from elected leaders, including Hawaii’s congressional delegation, and the community to shut down Red Hill after a leak from the facility in November contaminated the Navy’s drinking water system, which serves approximately 93,000 residents at Joint Base Pearl Harbor- Hickam and surrounding neighborhoods. The water contamination displaced several thousand military families who just began moving back into their homes in February. Some neighborhoods remain under “do not drink” water advisories as the state Department of Health reviews water samples to ensure that flushing operations have cleaned up any fuel left in the water.

The contamination was a crisis long in the making, say critics who have long tried to force better leak prevention at Red Hill or tank relocation, and the Navy’s response, which initially seemed to be marked with obfuscation and a downplaying of the extent of the problem, only inflamed tensions within the community and among regulators.

That weariness and simmering distrust of the Navy was not immediately assuaged by the defense secretary’s announcement, as skeptics questioned why the Navy hadn’t also announced Monday that it would drop its lawsuit against the state’s Dec. 6 emergency order requiring it to defuel its tanks, and withdraw its permit application before the DOH to continue Red Hill operations. “It would be nice to be celebrating, but we are not ready for that yet,” said David Kimo Frankel, an attorney for the Hawaii Sierra Club.

The Navy did not respond to questions from the Honolulu Star-Advertiser about whether it would now drop its lawsuit over the emergency order, which it filed in federal and state courts.

State senators also struck a cautionary tone during a news conference about the announcement.

“My concern, though, is that they will continue to slow-play this defueling process. It’s easy to state what your objectives are. It’s far more difficult to achieve that mission,” said Sen. Glenn Wakai, who represents the Pearl Harbor- Hickam area.

“Their track record of actually achieving some of their goals is a little bit spotty.”

Sen. Jarrett Keohokalole, who chairs the Senate Health Committee, also pointed out that the Navy has yet to submit two reports to the state that are critical to initiating defueling operations. One is a command investigation into the fuel contamination and leaks that occurred at the facility in May and November. The Navy says the investigation was completed in mid-January, but military leaders have refused to provide the media with an estimate of when it will be publicly released. The other report assesses the facility’s safety.

“Until we see those reports, we know for a fact that the Navy is not going to be able to take action,” Keohokalole said. “This is an important statement, but it’s really just the beginning of a series of concrete actions that the Navy still needs to execute in order for this situation to be resolved.”

Sen. Donna Mercado Kim said that in order for the Navy “to regain the trust of the community, I think they need to expedite these plans, and they need to do what they say they’re going to do, and they need to do it in a timely fashion.”

“I think that only at that time, if they live up to that, will the community then have trust in them again,” said Kim.

The Honolulu Board of Water Supply has shut down three of its wells as a result of the Navy’s fuel contamination out of concern that the pollution could migrate through the aquifer and pollute the municipal water supply, which would create a crisis on a much larger scale.

Ernie Lau, manager and chief engineer of the Board of Water Supply, said the wells will remain shut until it’s clear that the fuel contamination has been contained at the Navy’s Red Hill shaft.

“This decision has been a long time coming and we look forward to the final outcome,” Lau said in a news release. “We need a timeline from the Navy which identifies when the defueling and decommissioning of the facility will be completed.”

The Pentagon said Monday that Red Hill will be permanently shut down to further fueling operations, but it’s not yet clear what that will involve, including whether the underground tanks will be removed or filled in. A senior defense official also said other land uses may be evaluated for Red Hill.

“The main focus right now is on getting it safely defueled and then closing it,” the defense official told the Star-Advertiser. “What happens to the facility, the land after that, we just aren’t there yet.”

Austin pledged to partner with local elected officials and regulators as the military continues its environmental cleanup and reviews options for Red Hill.

“We will continue our work with the Hawaii Department of Health, national and local elected officials, and other community leaders, to clean up the water at the Red Hill well,” he said. “And we will develop an environmental mitigation plan to address any future contamination concerns. When we begin to consider land-use options for the property after the fueling facility is closed, we will stay in lockstep with communities in Hawaii. Nothing will be decided without careful and thorough consultation with our partners.”

Dr. Elizabeth Char, director of the state Department of Health, said the agency is “pleased with the Secretary of Defense’s decision to do the right thing for the people and environment of Hawai‘i.”

“This decision comes late for the Navy water system users who have borne the greatest burden of this humanitarian disaster, but it’s nevertheless reassuring that the imminent threat posed by this troubled facility will finally be addressed,” she said.

———

Star-Advertiser staff writer Ashley Mizuo contributed to this report.

Secretary of Defense Lloyd … by Ed Lynch