January has been declared Kalaupapa Month to commemorate the estimated 8,000 islanders who were banished to the isolated Molokai peninsula after being diagnosed with leprosy from 1866 to 1969.

“To wake up and know it’s Kalaupapa Month, it’s incredible,” said Anwei Skinsnes Law, author of “Kalaupapa: A Collective Memory,” which compiles patients’ stories in their own words, from letters and diaries, “most of them in Hawaiian,” and more than 200 interviews, in order to provide an “inclusive history, rather than the traditional history told over the years from the Western point of view.”

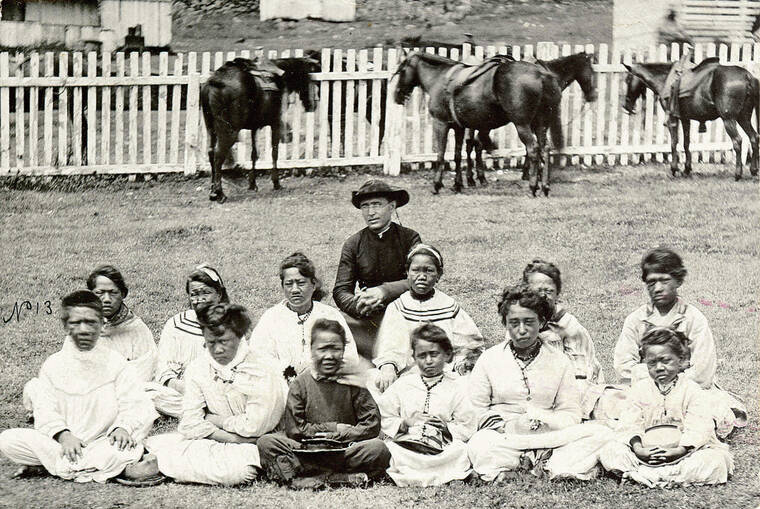

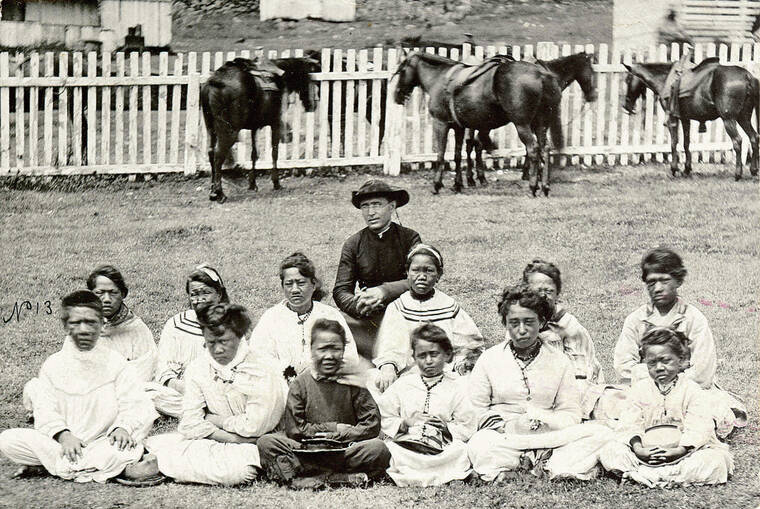

The history of the patients, at least 90% of whom were of Native Hawaiian descent, is still being discovered by relatives, many of whom grew up without knowing a member of their family had suffered from the cruelly stigmatized condition, now also known as Hansen’s disease.

Another author, John R.K. Clark, said, “For a lot of people, there was shame that someone in their family had contracted leprosy and been sent to Kalaupapa — that might have been the case in our family.” In 2012, Clark was finishing his book “Kalaupapa Place Names: Waikolu to Nihoa” when he learned from a relative that his Hawaiian great-great-grandmother, Emele, had died at Kalaupapa; his book is dedicated to her.

Clark became a member of Ka ‘Ohana o Kalaupapa, a nonprofit that has helped about 900 descendants reconnect to their Kalaupapa ancestors, and successfully lobbied the Legislature to pass a bill designating Kalaupapa Month, which was signed into law by Gov. David Ige in June.

Valerie Monson, a former Ka ‘Ohana o Kalaupapa executive director, points out that January contains significant dates, including the arrival by ship of the original 12 patients, who swam ashore on Jan. 6, 1866; and the birthdays of Father Damien and Mother Marianne Cope, who aided patients in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and were canonized in this century.

Additionally, there’s the arrival in January 1879 of Ambrose Hutchison, a part-Hawaiian patient who became a community leader; and in January 1978, the beginning of political rallies and a five-year occupation of Hale Mohalu, an alternative to Kalaupapa in Pearl City, by residents opposed to being transferred to Leahi Hospital by the state, which finally demolished the hale.

During Kalaupapa Month “we are hoping people will take time to say a prayer or just think about these people and what they went through,” Monson said of the patients and their families throughout 103 years.

In the 1940s it was discovered that leprosy was a bacterial infection, curable with antibiotics, yet Hawaii’s isolation law was not lifted until 1969, when many at Kalaupapa elected to stay on. Today nine survivors have the right to live at Kalaupapa, and five were living there this week, Monson said.

“However,” she added, “those of us with Ka ‘Ohana o Kalaupapa say there are still nearly 8,000 people living there — we feel them all the time.”

Kalaupapa Month also commemorates indigenous Hawaiian inhabitants of the peninsula, who taught the newcomers how to live off the land and sea but were evicted in full by the government in January 1895.

“Probably every Hawaiian family has a connection to Kalaupapa, over its 103-year history,” said Kerri A. Inglis, professor of Hawaiian and Pacific history at the University of Hawaii at Hilo and author of “Ma‘i Lepera: Disease and Displacement in Nineteenth- Century Hawai‘i,” which looks at the Hansen’s disease outbreak of 1865-1900 from the perspective of the patients.

For years, Inglis has been taking her students on two-week service trips to Kalaupapa, where they have conducted beach cleanups, planted native species and removed invasive species, and cleared overgrown cemeteries. In March 2020 she and a class were in the process of cleaning 1,200 headstones when COVID-19 orders took effect, but received permission to stay and complete their task.

“Most of the students who go on the trip with me are Native Hawaiian, and many learn they are related to people who were sent to Kalaupapa when they tell their families they are going there,” Inglis said. “It starts a conversation.”

Growing up on Oahu, Monica Bacon always knew she had an uncle who had been in Kalaupapa, but it wasn’t until decades later that she learned he had been Hutchison, who arrived in 1879 and served as resident superintendent.

“And I learned there were so many patients, Hawaiian people like him, who were leaders and helpers in the community,” she said, “(but) who I never heard of as a child.”

Hutchison’s father was president of the Board of Health under Kamehameha V and “tasked by the king to find a place where patients could be temporarily isolated, until they knew more about the disease — like with this COVID pandemic,” Bacon said. Before his son was diagnosed with leprosy, the elder Hutchison, whose wife was a Molokai native, selected Kalaupapa for the colony site.

Law said Ambrose Hutchison “has basically been left out of his own history,” but “he left us his memoirs, which will be published this year and which show he and Father Damien were the closest of friends because they had an expectation of justice and worked to get it.”

Unwilling to accept the loss of their families, homes and rights of citizenship, she said, Hutchison and other patients wrote letters to Hawaiian-language newspapers and petitioned the Board of Health, seeking better living conditions and permission for loved ones to visit them. Also, some wrote personal histories and music.

The late Rev. Dennis Kamakahi, a beloved Hawaiian musician and composer, is quoted on Ka ‘Ohana o Kalaupapa’s website as saying that the organization served as “the source by which I have reconnected with my family in Kalaupapa.”

He was referring to a cousin, Henry Nalaielua, also a talented musician, Monson said, adding, “Dennis said he did not know about him until later, never got to meet him.”

Together, Kamakahi and fellow slack-key masters Patrick Landeza and Stephen Inglis (not related to Kerri Inglis) gave a concert at Kalaupapa and released an album including songs written by Kalaupapa musicians, Inglis said in an email. Among the composers was the late Bernard Ka‘owakaokalani Punikai‘a, founder of Ka ‘Ohana o Kalaupapa and a world-renowned human rights activist, who had been separated from his family and sent to the isolated settlement as a child.

Due to the pandemic, the settlement has been closed to visitors since March 2020. Monson said the remaining kupuna, whom she speaks with, are in “remarkably good spirits.” She added, “They are strong and resilient, and their community has always come together to help one another in difficult times.”

“Kalaupapa Place Names,” Clark said, is filled with kanikau, lamentations that also celebrate the beauty of the natural setting, strong connection of Hawaiians to its land and sea, and their love for one another.

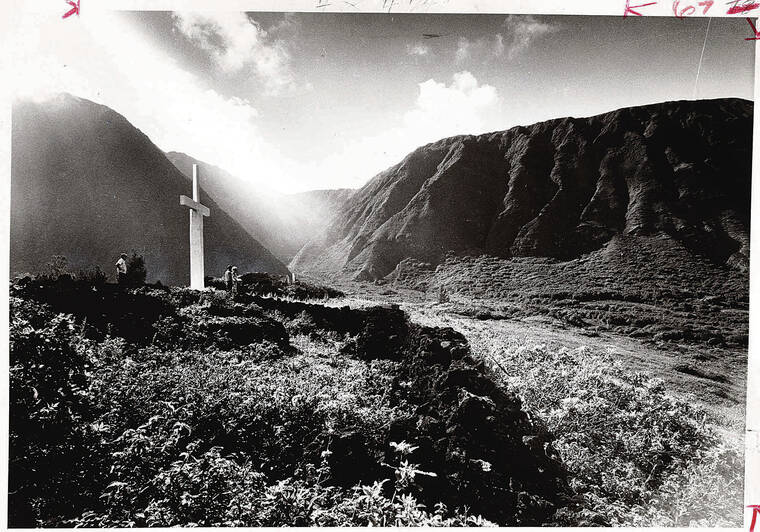

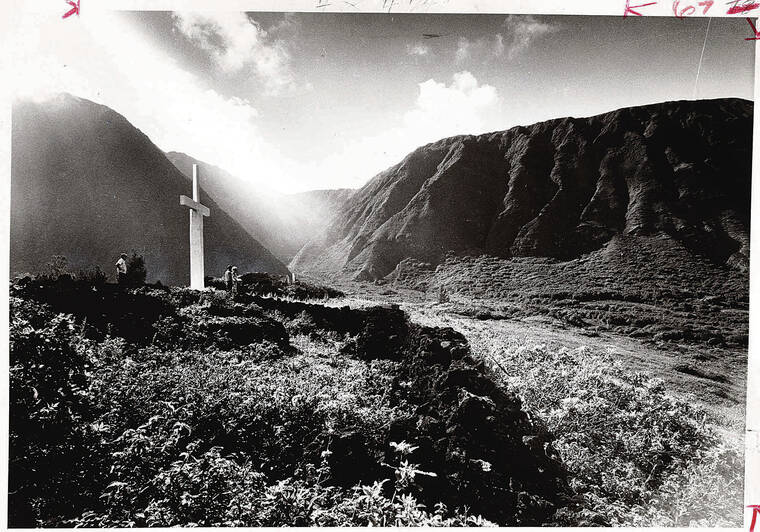

“They took my family away one step at a time,” a 1921 visitor wrote in a letter excerpted in Clark’s book, “(and) now, my eyes see the place called the ‘grave where the Hawaiian people are buried alive,’ but I am not wrong in saying, Kalaupapa is beautiful, on the bow of the ship, made majestic by what is above, the Ko‘olau cliffs.”

Noting it was common throughout Kalaupapa’s history for family members to go along with patients as kokua, to care for them, Law said, “It’s really a story of love.”

KALAUPAPA MONTH IN HAWAII EVENTS

In 1980, Kalaupapa National Historical Park was established to preserve the natural and cultural aspects of the peninsula and to maintain the home of the remaining residents, who were sent as Hansen’s disease patients to the isolated colony there, which was founded in 1866 and stopped admitting people in 1969; the disease, also known as leprosy, was found to be curable through antibiotics in the 1940s.

January has been designated Kalaupapa Month in Hawaii starting this year, and the nonprofit Ka ‘Ohana o Kalaupapa has organized a series of suggested actions, teaching ideas and events, including:

>> “The Restoration of Family Ties,” a free webinar hosted by the Damien-Marianne Catholic Conference, 10-11:30 a.m. Jan. 22. Pre-register at dmcchawaii.org Opens in a new tab.

>> “A Source of Light, Constant and Never Fading,” a free historical exhibit on display at the Nanakuli Public Library, 89-070 Farrington Highway, 1-8 p.m. Jan. 27 and 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Jan. 28, in partnership with Ahupua‘a o Nanakuli Hawaiian Homestead Association and the Nanaikapono Hawaiian Civic Club. For more information, call 668-5844.

A related exhibit is on display at ‘Iolani Palace, admission 9:30 a.m.-4 p.m. Tuesdays- Saturdays; for dates and current visitation information, visit iolanipalace.org Opens in a new tab.

For more events, activities and information, visit kalaupapaohana.org Opens in a new tab.

———

Mindy Pennybacker, Star-Advertiser