The Navy has been scrambling to contain the political and regulatory fallout from its water contamination crisis since confirming that jet fuel had polluted its Red Hill drinking water shaft in late November.

But 2022 is unlikely to bring any reprieve for military officials as candidates will undoubtedly seize on the issue of the Navy’s Red Hill fuel facility — the all-but-certain source of the pollution — in this year’s political elections, health and environmental regulators continue their pressure on the Navy to comply with an emergency order to drain the tanks, and the Navy faces a tidal wave of public opposition to its continuing operation of Red Hill.

The Honolulu Board of Water Supply and the Sierra Club of Hawai‘i, which in recent years have been at the forefront of raising alarm about the Navy’s aging fuel tanks, have vowed to continue their fight to force the Navy to permanently shut down the Red Hill facility.

“We will not stop,” Ernie Lau, BWS manager and chief engineer, told reporters Opens in a new tab last month.

Wayne Tanaka, director of the Hawaii Sierra Club, told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser that getting the facility defueled and decommissioned is a top priority in 2022, whether it be through the “courts, the political arena, or both.”

They’ve been joined in recent weeks by a growing activist movement that has attracted support from prominent Hawaii leaders.

While the recent fuel contamination has been confined to the Navy’s drinking water system that serves about 93,000 people in and around Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam, the Red Hill facility poses a growing risk to the freshwater aquifer that lies just 100 feet below the 20 massive underground tanks.

A history of leaks from the facility has polluted the groundwater beneath the tanks, tests show, while the risk of future leaks at the World War II-era facility is only expected to increase.

“The Navy has got to shut down Red Hill immediately, for good, or they are going to have this entire island against them,” activist Andre Perez told a reporter during a Dec. 12 protest in front of the headquarters of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. The demonstration was just one of several last month.

“Everyone drinks water. No one can drink jet fuel,” said Perez, who has been a leader in other protests including the fight against the Thirty Meter Telescope planned for Mauna Kea.

The BWS shut down its Halawa shaft and two other drinking water wells soon after the Navy confirmed the petroleum contamination in its Red Hill shaft, out of concern that the fuel will migrate across the aquifer and into its own drinking water wells.

The BWS provides water to the majority of Oahu’s 1 million residents. Top BWS officials say they aren’t sure they will be able to bring the Halawa shaft, which has supplied about 20% of the water to urban Honolulu, from Moanalua to Hawaii Kai, back online anytime soon. Oahu residents may be forced to conserve water in the summer months as demand increases, according to Lau.

In that case, the vitriol against the Navy will likely grow.

As the new year gets underway, the Hawaii Department of Health is expected to quickly rule on whether to uphold its Dec. 6 emergency order instructing the Navy to clean up contaminated drinking water at its Red Hill shaft, come up with a plan to drain its tanks and figure out what needs to be done to safely operate the facility.

Only then, health officials said, can the Navy ask the state for permission to resume operations. Under that timeline, it could be months before the Navy can resume fueling operations, if at all.

The Navy has been fighting the order through a contested case proceeding, which has further angered critics. DOH Deputy Director Marian Tsuji is expected to soon make a final determination as to whether the department’s executive order will stand.

But that could just be the beginning of a legal fight between the state and the Navy to drain the tanks. The Navy can appeal the decision in court. While Navy officials have not responded to the Star-Advertiser’s questions about whether it would do so, the Hawaii Sierra Club is already bracing for that legal fight.

The Navy also is in the midst of a separate contested case hearing over its state permit to continue operating the Red Hill facility, which has dragged on for several years. And it faces ongoing regulatory requirements, including studies and risk assessments of the facility, that are part of a corrective action plan handed down by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and DOH after 27,000 gallons of fuel leaked from the facility in 2014.

In an open letter Saturday to “the community of Hawaii,” Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro sent New Year’s greetings and said, “Your trust has been challenged with this past month’s drinking water contamination, and we know it is up to the Navy to repair that trust. We understand the hurt this has caused many of you, and we are committed to making it right … .

“Together with the Environmental Protection Agency, the Hawaii Department of Health, and the Military Services, we are working to ensure the Navy’s drinking water system complies with Hawaii’s safe drinking water requirements. We are being methodical, comprehensive, and safe to validate that our actions do no harm to any person or the environment. These collective efforts are the key to restoring safe drinking water as quickly as possible and enabling families to return to their homes.”

WHILE the legal and regulatory fight over Red Hill could be long and drawn out, the Navy also will be fending off increasing political pressure this year at the county, state and federal levels.

The Honolulu City Council has already introduced Bill 48, which would prevent anyone from operating an underground storage tank without getting a permit from the city. The permit would be granted only if the operator could show that the tank would not leak during its operating life.

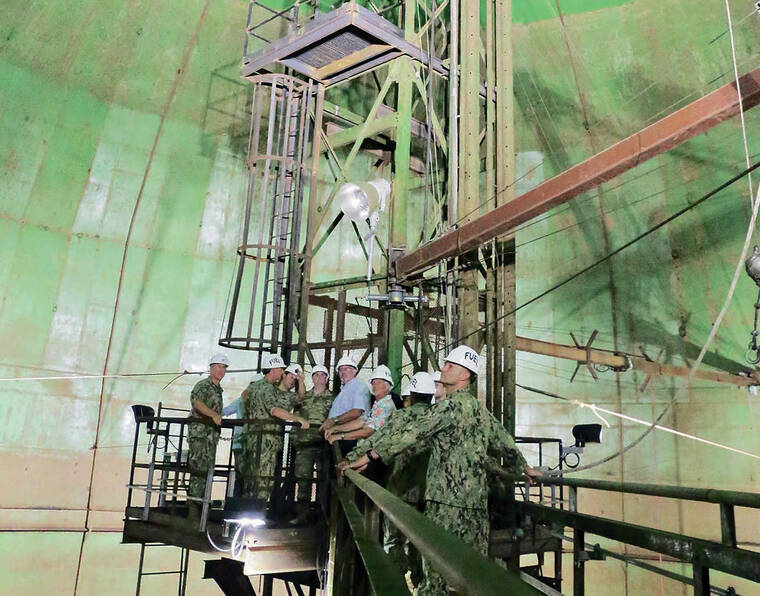

The Red Hill facility is capable of holding more than 200 million gallons of fuel in its 18 active tanks, each of which is big enough to envelop Aloha Tower.

The Hawaii Legislature also is zeroing in on Red Hill as it gears up for the 2022 legislative session, which opens Jan. 19.

Debates about Red Hill have dragged on for years, but Rep. Aaron Ling Johanson, who represents the area around Red Hill, said the current situation presents a “unique window” to usher in changes.

“The risk is potentially catastrophic,” said Johanson of the Red Hill facility. He said the fuel farm’s systemic problems present a “continuing and increasingly untenable risk for Oahu’s residents.”

Red Hill is already proving it will be a central theme in this year’s elections, with all 25 state Senate and 51 House seats up for grabs, an open governor’s race, and three out of the four members of Hawaii’s congressional delegation facing re-election.

Hawaii’s congressional delegation is already under pressure to take a harder line on Red Hill. While the delegation has sharply criticized the Navy during the recent water contamination crisis, its members have stopped short of calling for the tanks to be decommissioned.

The issue of Red Hill is also sure to play out in this year’s governor’s race.

Lt. Gov. Josh Green, an early front runner, has already staked out a position. He issued a statement Tuesday calling on the Navy to comply with DOH’s emergency order and also said the tanks must be drained and moved above ground.

“While I recognize the importance of the facility to the U.S. Navy, the risk of further leaks and spills is simply too great,” Green said in a statement. “We must prioritize the health and well-being of our residents and our environment.”

Hawaii Community Letter fro… by Honolulu Star-Advertiser