Puakea Nogelmeier can’t remember a day in recent years when he hasn’t logged on to the Papakilo Database Opens in a new tab. Sometimes entire days are spent looking up files and “following the wonderful rabbit holes” on the first-of-its-kind comprehensive database that hosts thousands of Hawaiian historical and cultural records, he said.

Now in its 10th year, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs’ database is more than just a storehouse of records to many people, according to Nogelmeier, who has helped the agency with Papakilo since its inception. The scholar of the Hawaiian language said it represents a treasure trove and offers important glimpses into Hawaii’s past.

“Hawaii as a whole has been disconnected from our actual history for a century,” said Nogelmeier, executive director of Awaiaulu Opens in a new tab, a nonprofit that develops resources to perpetuate and advance Hawaiian language and history. “What Papakilo does is it opens the doorways into all different parts of that history. It’s really critical to have the larger picture. The fact that there’s other collections that help illuminate that is invaluable.”

Over the past decade, OHA officials and community members say Papakilo has been a foundation and fills an important role in providing easy access to historical and cultural collections, from genealogies, Hawaiian- language newspapers and the oral histories of hula masters to land titles, letters by alii and government archives.

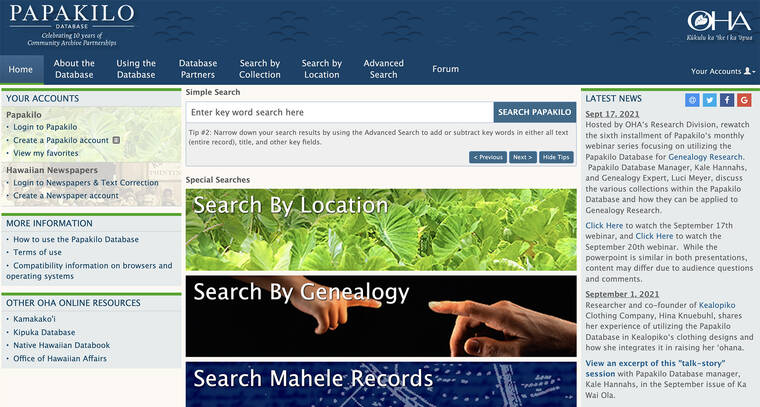

Launched in 2011, Papakilo is a free searchable public database that connects users to some of OHA’s collections and those of partner organizations that allow access to their records. Although many Hawaiian history resources exist, they weren’t available all in one place, according to Kale Hannahs, OHA’s research systems administrator and the lead on Papakilo since its inception.

The idea came about in 2007 as a way for OHA staff members to easily access environmental and cultural documents needed for reports. Prior to that, Hannahs said, staff members would have to make appointments to visit the Bishop Museum, the Hawaii State Archives and other institutions to get copies of documents.

That process was time- consuming and tedious, he said, especially when multiple trips to different locations were needed to pinpoint the records. By putting those records in a searchable database online, the public also can benefit, he said.

Over the years, Papakilo has grown from 13 collections with about 500,000 records from seven partner groups to 70 collections with more than 1.2 million records from 18 partners. The website has generated over 5.5 million views since 2011 from people in Hawaii, as well as from the West Coast, New York, France, England, New Zealand and other places.

“The idea was never to be the one and only source but to actually connect people to different databases,” Hannahs said. “I always liken Papakilo to being one of the roots of a tree. You follow it back to the source and it’ll open up to a myriad of different resources.”

Some of the first collections featured on Papakilo included land division documents, Hawaiian-language newspapers and genealogical and place names listings. One of those first partner groups was Awaiaulu.

Nogelmeier and Awaiaulu Programs Director Kau‘i Sai-Dudoit worked with Hannahs to add Ho‘olaupa‘i, a collection of Hawaiian- language newspapers, to Papakilo. They also provided OHA with the name Papakilo, which means a foundation for seeking, searching and observing.

Those newspaper archives provide firsthand accounts of what life was like in different periods of island history, Sai-Dudoit said. And those stories, she said, are not only useful to researchers but to anyone with an interest in Native Hawaiian and Hawaii history.

Both Sai-Dudoit and Nogelmeier said they have continued to work with Hannahs to identify other collections to bring on board. In 2017, they traveled to the East Coast to collect digital copies of records for Papakilo. They also are planning trips to England, New Zealand and Australia to do the same.

Nogelmeier pointed out that Papakilo isn’t enough on its own. He said the database is a good starting point that can lead users to other places to continue researching and learning more. What would’ve taken him a month of research many years ago now takes about five minutes, he said.

Sai-Dudoit agrees it’s been a game-changer.

“For a really long time, all Hawaii had to read about the history of our islands were written by foreigners without knowing that there’s this mass repository of writings by Hawaiians and about Hawaiians in their own language,” she said. “It represents Hawaiian knowledge.”

Another one of Papakilo’s partner organizations is the Hula Preservation Society Opens in a new tab, which began adding its oral history collections in 2016, said Executive Director Maile Loo-Ching. At the time, the nonprofit, which preserves and shares the stories of hula elders, didn’t have a way to host all of its archives and oral histories from the dozens of kupuna and hula masters collected over the years.

Now there are more than 1,200 hula-related records on Papakilo, including manuscripts, photos and newspaper clippings.

“The kupuna we have worked with over the last 20 years collectively represent a viewpoint of Native Hawaiians in the 20th century. They were born into a different Hawaii and grew up in a dynamic century,” Loo-Ching said. “It’s really important to understand their journey and the gratitude we have to them for preserving Hawaiian ways, music and hula.”

Hannahs credits Papakilo’s popularity to its partner organizations for getting the word out early on. He said he plans to continue adding more collections, including from the Institute of Hawaiian Language Research and Translation next year, as well as from the Kaua‘i Historical Society, Lahaina Restoration Foundation and Maui Historical Society in the future.

Lisa Watkins-Victorino, OHA’s research director, said the agency allocates funds for Papakilo and is committed to its growth. She added that going through its search engine is “like living history.”

To commemorate Papakilo’s 10th anniversary, OHA hosted several educational webinars. View the videos at facebook.com/officeof hawaiianaffairs/live_videos Opens in a new tab.

———

Jayna Omaye covers ethnic and cultural affairs and is a corps member of Report for America, a national service organization that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues and communities.