It’s not hard to imagine what the Hickam Army Air Field baseball field was like on Dec. 6, 1941. Hawaii seemed to have perfect and permanent baseball weather, especially to someone like Albert Joseph “Al” Konnick, a carpenter’s mate 2nd class born and raised in Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

The 25-year-old was close to getting out — six more days — so close that he likely could taste his mother Pauline’s holiday cooking that was sure to be extra special this year in honor of his homecoming.

George Jankavic and Apollonia “Pauline” Polacek had immigrated from what was then called Austria-Hungary in the early 1900s, with Jankavic becoming “Americanized” as Konnick. The two settled in Wilkes-Barre, married in 1905 at Sacred Hearts Catholic Church, and are buried in the church’s graveyard, where Albert’s government-issued grave marker and family headstone are placed.

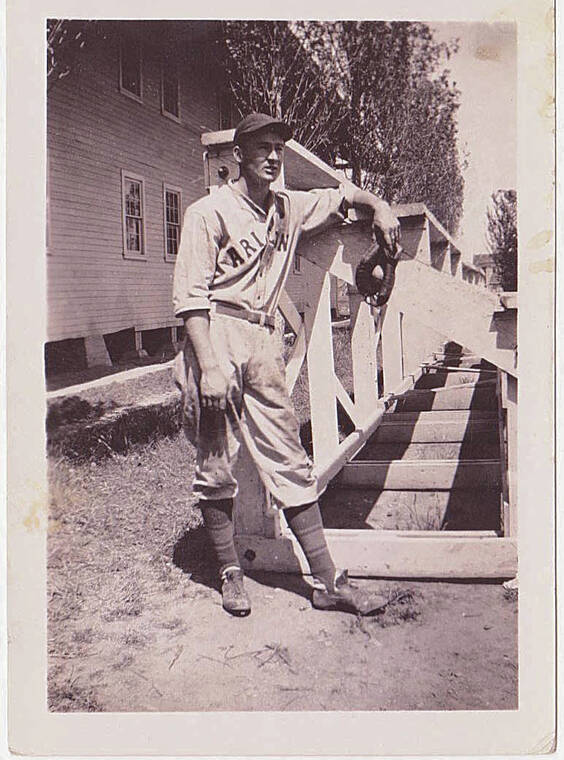

Konnick’s Navy career had begun just months after his 1935 graduation from James Coughlin Memorial High and his 19th birthday. Following Navy carpentry school, he joined older brother Andrew on the Arizona and on the Wildcats baseball team right before New Year’s Eve of 1936. They served together for eight months until Andy’s honorable discharge on Aug. 30, 1937.

The brothers were standouts on the ship’s baseball team that winter and spring. Posted on the USS Arizona Mall Memorial Facebook page, an undated account in the Arizona ship’s newspaper said the team had won four games in a row. In one game, a 5-1 victory over the USS Colorado, “the Konnick brothers again led the hitting parade, Andy getting three out of five, Al a home run and a single.”

A baseball and basketball standout at Coughlin, the athletic 6-foot-4 Al Konnick just knew his next career would be one he’d share with his uncle. Mike Konnick had been a catcher briefly for the Cincinnati Reds and was the former manager for the Wilkes-Barre Barons, a Class A team in the Eastern League. Uncle Mike still had connections and, according to Al’s great nephew Mark Konnick, the Chicago White Sox were interested.

Al Konnick was a standout first baseman, but, considered one of the best athletes on the Arizona, he was often behind the plate, as he was when the Arizona won the Battleship Division I.

“The last time I had talked to Albert he said he couldn’t wait to get back to civilian life. His mind was occupied with the prospect of playing professional baseball,” his sister Emily Harcarik said in a 1991 interview with the Citizens’ Voice newspaper in Wilkes-Barre. (Harcarik died in 1995).

A craftsman as well as an athlete

Al Konnick had been on furlough in Wilkes-Barre less than a month before his death, bringing with him a 1/16th-inch scale model of the Arizona he had built during his free time. It was a testament to his carpentry skills honed in the Navy, with 2,437 pieces — “no exterior detail was too small to escape notice,” one Wilkes-Barre newspaper reported. “It’s the work, not only of a craftsman, but of an artist.”

(The model was later displayed at a local store. Harcarik was pictured holding the model when interviewed in 1991, the 50th anniversary of the attack. A family member said its current whereabouts are unknown).

Perhaps Al went to the Battle of Music’s second four-band semifinal on Dec. 6 at Bloch Arena, the top two of which would face the bands from the Marine Barracks and the Arizona — 1-2 at the Nov. 22 semifinal — on Dec. 20 for the trophy. Just hours after that Saturday night performance, the entire Arizona band (Band Unit 22), while at battle stations passing ammunition under Gun Turret No. 1, was killed during the attack.

(The final was officially canceled on Dec. 20, with surviving band members voting unanimously to award the trophy to Band Unit 22 and renaming it the Arizona Trophy).

No one knows for sure exactly where Al Konnick was at the time of the attack. Sailors from the Arizona and the other seven ships at anchor on Battleship Row were topside for 8 a.m. “Morning Colors,” the bugler from the Nevada having played “First Call” at 7:55 a.m. and the prep signal having been run up.

According to historical accounts, the 23-member Nevada band had begun playing the national anthem at 8 a.m. and continued to play while the Nevada, astern of the Arizona, was being strafed by some of the 183 aircraft from the Imperial Japanese Navy. The band famously rushed through the end of the anthem, broke formation and ran for cover — the scene forever documented by the epic war movie “Tora! Tora! Tora!” The Nevada was the only ship to get underway and was headed out the channel. Her escape ended when, after taking on water due to a torpedo hit leaving a gaping hole on her port side, she was run aground purposely at Hospital Point so as to not block the channel.

News updates coming out of Hawaii were slow and heavily censored, the territory put under martial law within hours of the Dec. 7 attack. Konnick’s father, George, received a hand-printed letter from Rear Adm. Randall Jacobs, chief of the Bureau of Navigation, dated Dec. 20, 1941,

It read, in part, that “Your son, Albert Joseph Konnick, is missing in the performance of his duty and the service of his country. The department appreciates your anxiety and will furnish you further information when received. To prevent possible aid to our enemies please do not divulge the name of his ship or station.”

His family knew Al’s rack was on the other side of the compartment holding explosive ordnance, and they were told he likely was incinerated instantly when a 1,760-pound bomb — the fourth direct hit suffered — crashed through five decks and detonated the forward powder magazine at 8:06 a.m. The blast was so intense that it lifted the 33,000-ton ship out of the water and instantly killed 1,177 of the 1,512 sailors and Marines that were aboard.

Remains listed as unrecoverable

Records list Al Konnick’s remains as “unrecoverable.” Awarded the Purple Heart posthumously, his name also is inscribed on the Ewa wall of Court 3 in the Courts of the Missing at Punchbowl, on a white limestone panel where he is listed in between Bernard A Konitzer of Wisconsin and Peter Konosky of Pennsylvania, just one name among the 588 on that single wall. (Off those 588, only six have been officially identified).

There were 38 sets of brothers on board the Arizona that devastating day, not 39, as one of the Wilkes-Barre newspapers initially reported on Dec. 20. The paper made the grievous mistake of stating that the two youngest of George and Pauline Konnick’s three sons were to be on the warships that were sunk and ran an old photo of the two brothers wearing Arizona baseball uniforms. But Andy had left the Arizona over four years earlier, was married and continued the electrician’s trade he had learned in the Navy.

A number of minor leaguers died during the Pearl Harbor attack, some on the verge of “getting the call” when the draft called instead.

The Al Konnick story epitomizes the promise and potential lost that day. The reality of life is not always of one’s own choosing and we will never know if Konnick would have had a major league career.

Truly, fate can be such a harsh pinch hitter.

This was originally meant to be a column, and there were so many ways it could have gone. Hawaii has such a rich tradition of baseball, going back to Alexander Joy Cartwright, often referred to as “A Father of Base Ball,” who was Honolulu’s fire chief (1850-63) and is buried in Oahu Cemetery.

There are a number of well-researched books such as “Transpacific Field of Dreams” and “Baseball in Hawai’i during World War II,” the latter’s cover with a 1944 photo of Furlong Field and a Navy lineup that included Phil Rizzuto, Johnny Mise, Peewee Reese and DiMaggio (Dom, not brother Joe). Furlong Field was considered “the Navy’s premier ballfield, according to author Gary Bedingfield, who gently described the field’s demise when “absorbed” by the expansion of what is now Daniel K. Inouye International Airport.

There was inspiration from the wonderful reporting by the Star-Advertiser’s William Cole on the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency recovery and identification of missing American war dead. Cole chronicled the reunification of the Trapp brothers Harold and William, both killed on the USS Oklahoma, who were among the 388 co-mingled remains interned in 62 caskets at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific as “unknowns” but disinterred in 2015 and later ID’d. The brothers have been reinterred at Punchbowl with separate grave makers and caskets, buried one above the other.

There was a thought about making a push here for an “Arizona Project” similar to what was called the “Oklahoma Project.” In June, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency proposed disinterring 85 of the USS Arizona unknowns at Punchbowl, reinterring them on the sunken battleship with over 900 shipmates but without being identified.

That didn’t seem to be the logical thing to do, given the success with the Oklahoma Project. But logistically, perhaps not feasible — according to a DPAA official, the lab only has 12 familial reference samples of the 1,177 Arizona crew members who died.

Maybe, more than anything, it is the love of baseball and its history that I share with former Star-Bulletin/Star-Advertiser colleague Jerry Campany, himself a Marine veteran, that led to this. Among his random baseball postings on Facebook was a copy of the Star-Bulletin story of the Arizona winning the group crown over the Nevada.

His comment above the article begins: “A quick glance tells me that every player in this story died at Pearl Harbor except for (Bo Beau) Claire and (Cap) Shapely.”

For some reason, I needed to check. Most do have their names on one of the memorials, while others — such as Claire, Shapely and “Turkey” Thompson, who caught Heath and had an RBI for the Nevada in that title game— don’t.

Konnick’s name was found at the Courts of the Missing at Punchbowl, and that of his battery mate, George “Lefty” Perkins.

The Arizona unknowns were remembered Saturday at Punchbowl, a ceremony that included family members of Arizona survivors. Randy Stratton, son of Donald, who died in 2020, was in a group that planted flags at the grave sites marked “Unknown” of the co-mingled remains of sailors and Marines from the Arizona. (Estimates range from 85 to 124 remains that are unidentified).

In a phone call prior to his visit, Randy Stratton said his dad made a point of one thing before he died regarding the identification of his shipmates.

“Randy, don’t let them forget.”

That is the true reason for this story, for Al, Lefty, Portsider, and all the others lost 80 years ago.