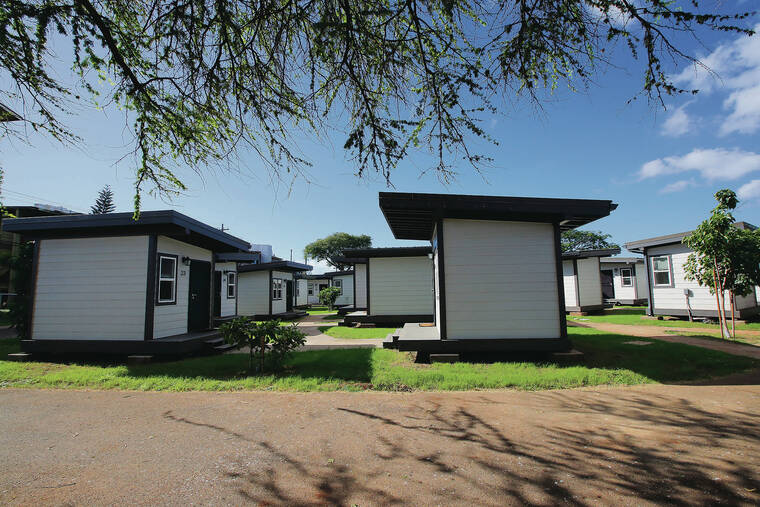

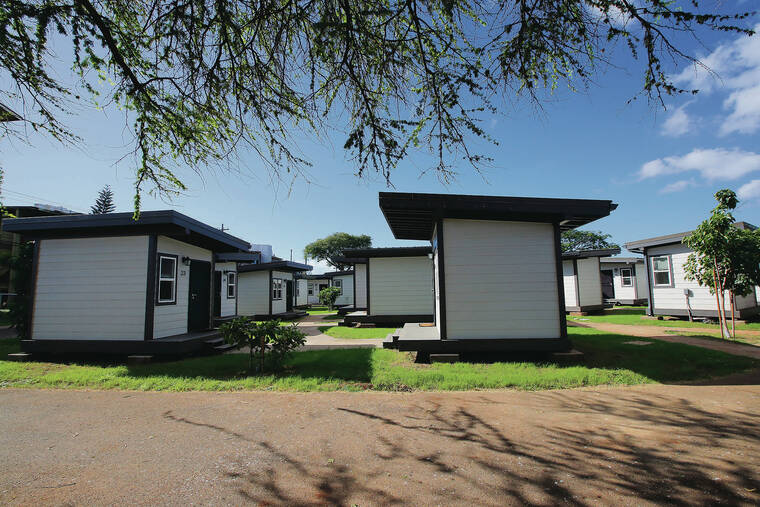

The final touches are being applied to Hawaii’s first “kauhale” of 100-square-foot homes in Kalaeloa, providing permanent housing for some of Hawaii’s chronically homeless and most-troubled people living on the street and in shelters.

There are 37 homes in the kauhale, which is named Kama‘oku.

The concept was borrowed from Austin, Texas, and built under an emergency proclamation by Gov. David Ige with the Hawaii Public Housing Authority collaborating on construction with HomeAid Hawaii, the local chapter of a nationwide organization of builders, contractors, developers and others working to improve their communities.

Kama‘oku was built on 1.5 acres of decommissioned Naval Air Station Barbers Point land off Yorktown Street.

HomeAid Hawaii volunteers and their children as young as age 5 helped assemble furniture and decorate each tiny home, said Nani Medeiros, HomeAid Hawaii’s executive director.

Doormats on each lanai read “Home Sweet Home,” “Yay! You’re Here” and “There’s No Place Like Home.”

The homes can accommodate 36 residents and an on-site property manager. HomeAid Hawaii members donated 19 of them and the state paid for an additional 18, each costing about $20,000 each, Medeiros said.

Because of rising construction material costs and global supply-chain issues, similar projects could cost as much as $22,000 per unit, she said.

The first residents are scheduled to move into their new, individual homes on Friday.

At Kama‘oku, the newly housed residents will receive medical, mental health and other treatment, services, and job preparation and training through U.S. Vets, which is located just a few minutes’ walk nearby.

They will be invited to join the U.S. Vets’ annual Christmas wish list program, which allows donors to fulfill the needs of clients online, said Darryl J. Vincent, who is based in Kalaeloa and is the chief operating officer for the U.S. Vets program across the country.

Although the new housing and programs are being managed by U.S. Vets, they’re available to homeless people with or without a military background.

HAWAII, like other communities on the mainland, works to place the most chronically homeless people into individual, fair-market apartments through the Housing First program that includes social service assistance.

The kauhale program instead emphasizes creating affordable communities, and the Kama‘oku homes were designed to face each other so residents can interact, grow vegetables that they’ll eat, and gather in communal indoor and outdoor spaces. A commercial kitchen is intended to serve as a culinary training program.

The community’s outdoor covered pavilion — cooled by two overhead ceiling fans — also could serve as a gathering space for any number of community organizations.

Members of the community already interact with homeless clients at U.S. Vets to teach yoga, aerobics, Zumba and math, among other courses, Vincent said.

“I truly believe that the way to solve (the) homeless (problem) is integration and not isolation,” Vincent said.

Each tiny house is wired for electricity and comes with a ceiling fan. U.S. Vets is responsible for the utility costs.

There are separate men’s and women’s communal restrooms and showers, and an on-site medical facility — a renovated 2,800-square-foot dilapidated building from military days.

Each resident is expected to pay $500 a month in rent. Those who cannot pay the entire amount will be subsidized through a city housing program, Vincent said.

But the goal is to get everyone employed and given counseling on managing their money. Some residents might stay indefinitely, while others may move on, he said.

The kauhale concept was introduced by Lt. Gov. Josh Green, whose dream of a statewide system of six to eight projects across the islands suffered a setback in the 2020 legislative session when two House committees voted to study the concept rather than move out a bill that would have provided $20 million for a one-year pilot program.

“I deeply appreciate the hard work of HomeAid Hawaii and our builder community that came together with all their generosity and support to make this project happen,” Green wrote in a text to the Honolulu Star-Advertiser last week.

“The Kauhale model can be quickly replicated across the state in regions where our local leaders determine the greatest need. Housing is healthcare proven by every health metric we measure in society, and my team and I remain committed to bringing about more of these so-called solutions where they are needed most.”

IT’S HARDLY HomeAid Hawaii’s first effort to help reduce homelessness through construction and renovations in Hawaii since the local chapter was formed in 2015.

Previous efforts have helped a growing list of organizations addressing homelessness, including the Institute for Human Service’s Tutu Bert’s House and VET House; the city’s Pauahi Hale in Chinatown; the YO! Waikiki drop-in center for homeless youth; Next Step Shelter in Kakaako; RYSE Hawaii on the Windward side; and the Ka‘a‘ahi Women and Family Shelter.

HomeAid Hawaii is now working on three other ongoing homeless-related construction projects.

“An important distinction for Kama‘oku is that it is a permanent community, not an emergency or transitional shelter that people will have to leave after a certain time. It was important to me that HomeAid Hawaii took the next step in our work and built permanent housing inventory to address the homelessness crisis,” said Harry Saunders, HomeAid Hawaii’s board president and president and CEO of Castle and Cooke Homes HI Inc., in a statement.

Ryan Watanabe, vice president of his family’s M. Watanabe Electrical business that was started by his grandfather, said it was important for his family and employees to be part of Hawaii’s first kauhale.

M. Watanabe Electrical previously helped Habitat for Humanity build one home each year for a needy family. But the kauhale concept was different, Watanabe said as he unlocked residential units and communal spaces at Kama‘oku for the Star-Advertiser.

“You’re really affecting a lot of lives here,” he said. “This is a community.”

M. Watanabe Electrical brought in heavy equipment to do grading and other work, and relied on 40 of its 70 employees to install electrical outlets and ceiling fans that the company donated and connect each tiny house to power.

Some of the employees even brought their children to two community events to help finish the project.

When it was over, Watanabe said his employees’ response was universal: “How can we do more?”