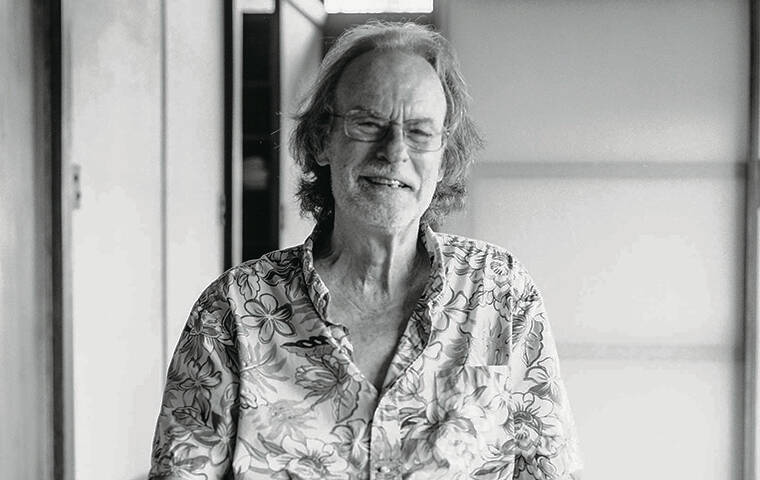

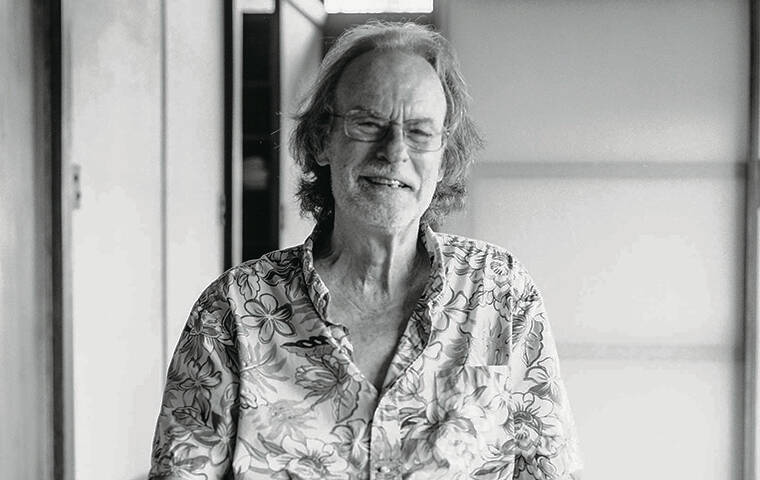

Bob Liljestrand, a documentary filmmaker, photographer and architectural historian, died last month at the Liljestrand House — his historic family home on Tantalus Drive.

Liljestrand died outdoors on the lawn high on a hillside overlooking downtown Honolulu and the sea on Oct. 23, his wife, Vicky Heldreich Durand, said.

“We wheeled his hospital bed underneath the deck of the house, in the shade,” his son, Shan Liljestrand, said. “That’s where he requested us to stop. You could see the view really clearly.”

It was a view Bob Liljestrand had fought to retain.

After his father’s death in 2004, he worked to preserve the airy house with its soaring lines and picture windows, designed by modernist architect Vladimir Ossipoff. Liljestrand’s parents, Howard and Betty Liljestrand, a medical doctor and nurse, bought the hillside site in 1948.

Born in Aiea on Dec. 23, 1941, Bob Liljestrand was 79 years old. The cause of death was liver cancer, Durand said.

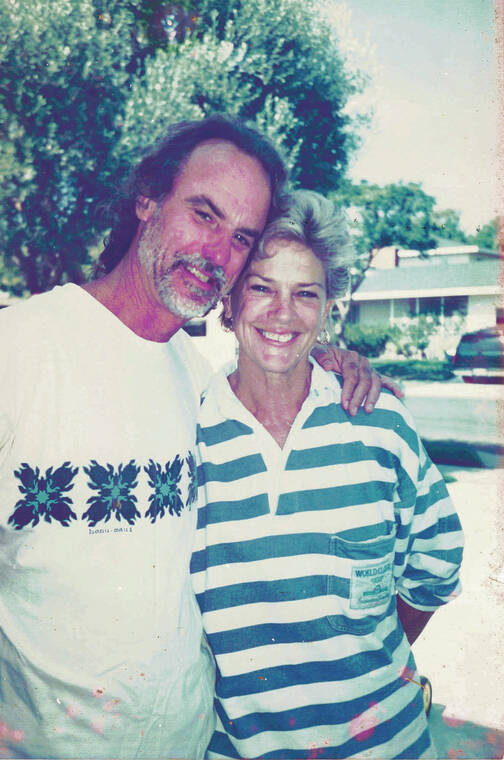

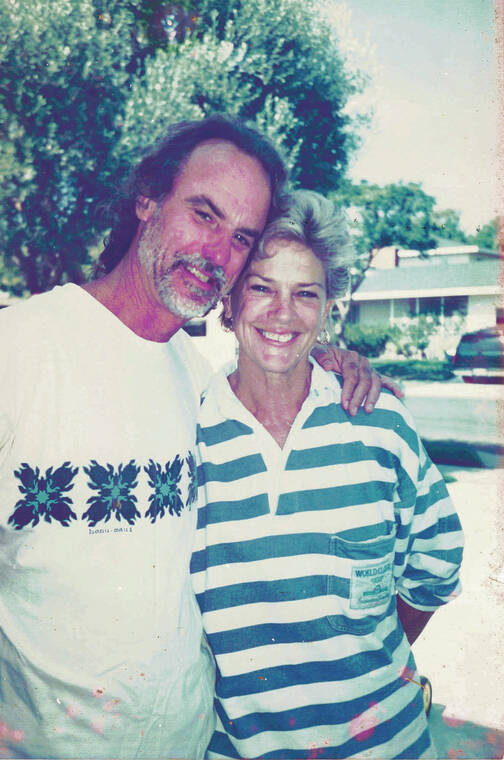

“Bob didn’t want the house to be sold to private owners who would add their own touches to an Ossipoff masterpiece — he wanted to save it for education and the community,” said Durand, a Punahou ’59 classmate who became friends with Liljestrand 40 years later. They married in 2013.

The couple co-founded the nonprofit Liljestrand Foundation, whose mission is to preserve the house, opening it to the public for tours and charitable, cultural, and educational activities.

Liljestrand and his brother Eric Liljestrand, who died in 2016, sold their own homes in order to pay estate taxes for the Liljestrand House, and in 2015 the house was gifted to the foundation with the stipulation it could never be sold for the benefit of an individual.

Foundation board members said Liljestrand would be deeply missed.

“Bob was such a stable and clearsighted person, and a dear friend,” said Dean Sakamoto, principal of Dean Sakamoto Architects/SHADE Group, who first met the Liljestrands while researching a 2007-2008 retrospective exhibition “Hawaiian Modern: The Architecture of Vladimir Ossipoff,” which he curated, and a book of the same title he co-authored.

“He was a sensible guy but also a visionary, and willing to not know all the answers,” Sakamoto said. “He had his own style, very kind and thoughtful, and he was nurtured by great parents and grew up in a great house, all of which produced a great man.”

Bill Chapman, dean of the School of Architecture at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, said Liljestrand had a gift for bringing people together, including the architects, educators, writers and environmentalists from all over the world who participated in presentations, design seminars and other events hosted by the foundation.

“Bob was generous, always, to everyone in every way, from those starting out in their careers to visitors to the Liljestrand house,” said Chapman, who helped him enter the house, “a distinctive piece of tropical modernism and preeminent example of modernist domestic architecture in Hawaii,” onto the historic registry.

“He was at all times polite, with a terrific sense of humor,” Chapman added, “and he faced his illness with great bravery, philosophical to the end.”

Shan Liljestrand, 31, a Los Angeles director of photography, remembered “doing a lot of hiking on Maui and Oahu” with his father, and taking boat trips to Kaneohe Sand Bar and Rabbit Island on Liljestrand’s 23-foot Seacraft motorboat, “which he was very proud of, a dry boat that handled open water and rough seas well.”

As the youngest member of the Liljestrand Foundation board, “I’m incredibly grateful my dad involved me with the house, and to all the people I’ve been able to work with from different worlds and different generations,” he said.

A 1959 graduate of Punahou School, Liljestrand earned a bachelor of science degree in biology from San Jose State University in California; a master’s degree in public health from the University of Hawaii; and a master’s degree in architecture from the University of New Mexico.

He worked as a hospital administrator at the Leeward Hospital and Clinic, as a designer and draftsman for a Honolulu architect, and in his family’s real estate business.

His photography appeared in “Artists of Hawaii 1982” at the Honolulu Academy of Arts, and his documentary films were shown locally and at the Los Angeles International and Chicago film festivals.

At the Chicago festival, he won a Gold Plaque for “Molokai Solo,” which chronicled lone journeys by water and foot along the island’s rugged windward shore. In one of the island’s remote valleys he built a campsite with a stone platform and rainwater catchment system.

Additionally, Liljestrand documented a 14-day raft trip through the Grand Canyon made by a chamber music ensemble that played music throughout; and an 8,000-mile trip by train and river boat through western China with his father and uncle, who grew up in Chengdu, Szechuan, where their parents served as medical missionaries.

But he dedicated the last 17 years of his life to researching the history of his parents and their house, helping establish the foundation and its programs, and co-authoring a forthcoming book, “Architecture: the time, the place and the people,” which tells the story of his family and the Liljestrand House and is being designed by Barbara Pope.

“He’d had a happy childhood growing up in the house, with these parents that wanted to build, not a fancy house but just a plain house, out of plain materials,” said Durand, who recently published “Wave Woman,” a memoir of her own mother.

A board member of the Hawai‘i Architectural Foundation and the Adventurers’ Club of Honolulu, where he served as president five terms, Liljestrand was also a member of the advisory council to the School of Architecture at UH Manoa.

He lectured widely on the Liljestrand House, including at the American Institute of Architecture in New York, and the national museum of architecture in Frankfurt, Germany, where the Ossipoff exhibition had traveled.

IN A letter of application to the Ossipoff designed Pacific Club on Queen Emma Street, Liljestrand said, “…as a lifelong friend and acquaintance of Ossipoff, I simply enjoy being in the building.”

“Bob was a great storyteller; he was terrific at giving extemporaneous presentations about the (Liljestrand) house, and the way his parents consulted with Ossipoff (who also designed the furniture and fixtures and selected the artwork) every time they made a change, long after it was built.”

Liljestrand especially enjoyed the collaborative relationship between his mother and Ossipoff, “which really was a team effort,” Sakamoto said, particularly regarding the kitchen.

“I’ve never seen any other Ossipoff kitchen like that— it’s really a Betty Liljestrand kitchen,” he said, “a larger, but open kitchen with an island, a breakfast nook and dining room nearby — a precursor to nowadays.”

The house is also an early and enduring example of sustainable design, Chapman said.

“It was designed with the environment in mind—it exemplifies indoor/outdoor living,” he said, “working with nature rather than against it (to provide shade beneath decks and eaves, and cooling through windows using prevailing breezes) without air conditioning.”

Shan Liljestrand said his father’s careful research and organization in matters for the house contrasted with an unstructured, open-ended approach to travel, which was “never have too much of a plan, only just enough.”

His father loved road trips, “but I especially remember our first trip to Southeast Asia, when I was 24,” he said. “We walked for two hours in Ho Chi Minh City and somehow ended up on the other side of the river, and then Dad hailed a man on a tiny scooter, who took us back to our hotel.”

Liljestrand worked on his book with the writer Julia Steele, with whom he shared materials from the house’s archive room and notebooks he had filled, Durand said.

During the last weeks of his life, she said, Steele called Liljestrand every morning and read him one or two chapters over the telephone.

After Liljestrand had heard the entire book, a few days before he died, “he told me he’d felt the need to do this book about his parents, but he didn’t expect me to tell his story,” Shan Liljestrand said.

“He said, ‘go and do whatever you want—have fun.”

“Bob was very adventurous, courageous, hardworking and honest, with big dreams,” Durand said, noting her husband had worked up until his last few days. “He was going for the moon.”

In addition to his wife and son, Liljestrand is survived by daughter Briana Liljestrand Lawrence (Andrew) of Denver, Colo.; sisters, Wendla Lei Liljestrand of Honolulu, and Lana Lee Craigo of Fair Oaks, Texas; stepdaughters, Marcie Durand Garner and Rennie Durand Turner; and eight grandchildren.

His previous marriages, to Diane Helbush and Carol Clark, ended in divorce.

Private services are pending; in lieu of flowers the family suggestions donations be made to the Bob Liljestrand Preservation Fund at liljestrandhouse.org Opens in a new tab.