An innovative offshore fish farm designed to “swing” with ocean currents while sustainably scaling up food production could be placed in the water off Ewa Beach, but concerns about its possible environmental impacts persist.

Hawaii-based mariculture company Ocean Era, formerly known as Kampachi Farms, has proposed the aquaculture farm, which it wants to place about 2 miles offshore from Ewa Beach. The project is still in its early planning stages, and the company is still applying for permits while consulting with different organizations and entities.

A publicly available draft environmental review Opens in a new tab has been posted on its website.

The offshore fish farm would be just the second in Hawaii. The only commercial operation in the state is Blue Ocean Mariculture’s kampachi farm, about a half-mile from shore in North Kona. One of the founders of that farm, and a pioneer in Hawaii mariculture, was Ocean Era co-founder and CEO Neil Sims, who is now trying to open another farm.

Ocean Era is asking for a 15-year lease to use about 450 acres of state water to deploy its farm. The company anticipates that after a few years the farm will produce about 2.2 million pounds of fish annually, and a “large majority” of it will be sold on Oahu.

The company wants the farm to serve as a “commercially viable model for environmentally sound offshore aquaculture” that can increase food production for a growing population.

“We’ve got a global climate crisis that is also compounded by the shortage of arable land, the shortage of fresh water. And organizations like the United Nations … have recommended that humanity needs to get more of its food from the sea,” Sims said.

The U.N. estimates that the global population will reach 9.7 billion people by 2050, and has promoted ocean-based food production Opens in a new tab as playing a “major role” in ending world hunger. Fish farming has been one of the world’s fastest-growing food sectors during the past 20 years, and it has been found to produce fewer greenhouse gases than the farming of livestock.

Ocean Era’s farm would also contribute to local food production and food security in Hawaii, which currently imports about 90% of its food. Ocean Era noted that the state has the highest per-person consumption of fish in the country, but 63% of the fish sold locally is imported.

Sims said construction could start in mid-2022 and take about three to five years to complete, although its first harvest could come in 2023. The capital cost of the farm will be about $2 million to $3 million, Sims said.

Two species of fish and macroalgae, or limu, will be raised on the farm. The fish species include nenue, a native fish also known as the brassy chub. The second fish would be moi, a native fish that was traditionally eaten only by Hawaiian chiefs. The limu species are still being decided on but could include ogo, limu kohu, limu lipoa and sea grapes.

Nenue would be a new fish species introduced to market, Sims said, and the limu species, aside from ogo, would be new as well.

Moi is well known for its taste, although that is not the case for nenue — at least to Western palettes, according to Ocean Era. Nenue was chosen in part because it is herbivorous and can eat the limu that would be grown at the farm.

The company said the cost of feeding fish is about 60% of operating costs for most farms. Growing a herbivorous species and limu could reduce the feed expenses, and those savings can then be passed on to consumers.

But perhaps more important is that the limu and herbivorous fish are also part of the proposed farm’s design, which is meant to mitigate the environmental impact generally associated with offshore fish farms.

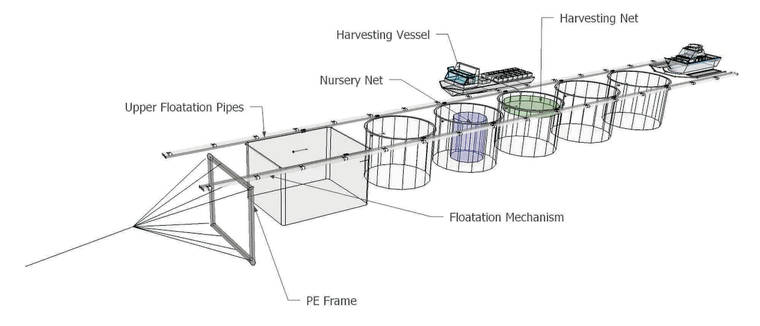

Offshore aquaculture farms like Blue Ocean’s normally use stationary submersible pens to grow fish, but Ocean Era plans on deploying two rows, or arrays, of fish and limu pens, and each would swing with the ocean’s currents around an anchored “swivel.”

The swivel design is used by an Israeli-based company, Sims said, but is more commonly used by ships mooring offshore.

Each array would consist of five pens — four 30-by-14-meter pens closest to the swivel anchor to raise fish, and a fifth and farthest pen to grow limu. The configuration would ensure that the seaweed pens are positioned to be in constant exposure to nutrient-rich effluent coming from the fish pens.

“The innovation that we are wanting to apply here is the idea of having the limu downcurrent from the fish pens,” Sims said. “That performs two functions: It provides the nutrients for the limu, so we would be getting more robust growth from the limu, but the limu are |going to be taking up the nutrients that are flowing from the pens.”

For decades there have been concerns about the cleanliness of fish farms, and they persist today, as the U.N. notes. Among those concerns is the effluent, or waste, produced by fish that is then released into the surrounding waters and can be harmful to nearby marine environments.

The location of an offshore farm plays an important role in its ability to deal with waste. Sims and Todd Low, manager for the state Department of Agriculture’s Aquaculture and Livestock Support Services, said the currents in Hawaii help disperse waste.

“It comes back to the currents. … Here we have just ripping currents, typically, and that pretty much blows everything away,” Low said.

Cleanliness issues were a bigger problem decades ago, Sims said, but are less so now as the industry has matured.

“What’s happened in the last 40 years … as people have moved into deeper sites and better currents, they’ve found it’s better for the fish, and it’s better for the environment,” Sims said. “If you move to deeper water farther offshore, the impacts are often not even measurable.”

Ocean Era wants to put its farm near the site of an offshore moi farm that went out of business and was not known to be deleterious to the environment, Low said.

Despite Ocean Era’s proposed design and location, the environmental concerns that come with offshore aquaculture linger.

Neil Frazer, a researcher at the University of Hawaii’s School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, commended Ocean Era for its plan to culture limu but said the best method of aquaculture is land-based.

Frazer, who for years has studied aquaculture farms and their associated diseases and pathogens, said in an email to the Honolulu Star-Advertiser that “a sea-cage operation is much like a small town dumping raw sewage into the ocean” and that diluting the waste is not a solution.

He’s also unconvinced that the limu will absorb much of the effluent, saying that limu have already adapted to Hawaii’s nutrient-poor waters.

Sierra Club Hawaii Chapter Director Marti Townsend also liked Ocean Era’s idea to address the waste issue by growing limu, but did not approve of the project. She had not reviewed the proposal, but she said the environmental advocacy group normally finds offshore farms problematic because of the effluent they produce as well as their proclivity for spreading diseases, which is often promoted by the crowding of fish.

“Generally, we have issues with offshore aquaculture because it’s dirty,” Townsend said.

Waste, disease and feeding make up the “most important issues in sea-cage culture of finfish,” according to Frazer. He argues those issues aren’t adequately addressed in Ocean Era’s draft environmental review. Ocean Era has said the draft will be revised as planning continues.

Frazer said the review does not include a list of the parasites associated with the farmed fish species and of the species of nearby wild fish with the same or similar parasites, but it should because disease transfer between farmed and wild fish has been shown to be a problem around the world.

“In every country with sea-cage aquaculture, nearby wild fish of the same or similar species have declined, sometimes catastrophically,” Frazer wrote.

Feeding the fish, specifically moi, would be an issue because it is a carnivorous species. Nenue might be sustained by limu, but moi would require fish oil in its diet, and that fish oil would have to come from harvested wild fish.

“To obtain the necessary fish oil, the industry buys large amounts of forage fish in less-developed (countries) such as Chile and Peru, converting them to fish oil and fish meal,” Frazer wrote, and for moi in particular, “two to four pounds of edible wild fish must be extracted from the ocean to grow one pound of moi.”

The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization said in a 2009 report Opens in a new tab that a growing demand for fish around the world could lead to the over-exploitation of wild fish stocks that are used for fish meal and fish oil.

Frazer and Townsend have compared commercial offshore fish farming practices to traditional Hawaiian fishponds, which are less viable when it comes to producing fish at scale but are able to control for disease and environmental issues associated with offshore fish farms.

However, Sims said the economic viability of the project, or any other that aims to be sustainability and environmentally conscious, cannot be ignored.

“We want to find the economic incentives that address the ecological imperatives that we face,” he said. “We’ve got to be able to build sustainable businesses that answer the burning issues of our day, because that’s the way you scale it. Because if you’re relying on foundations and donations to go and solve global warming, you are so screwed.”

Regardless of what aquaculture might look like in the coming years, it’s clear that it’ll grow to be an important part of food production worldwide.

Low, in line with the U.N., said fish will replace terrestrial meat as the primary source of protein for people, noting that fish grow faster than livestock, and more can be farmed in the same amount of space.

“Aquaculture is a global thing; it’s exploding across the world. This is, I think, where we’re going to feed the most people,” he said. “As our global population grows, fish will be the protein of the future.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misidentified nenue as a “rare” fish species. The story was also updated to clarify that the Sierra Club’s Marti Townsend does not approve of Ocean Era’s proposed aquaculture farm.