Dozens of kumu seek to preserve, protect hula at inaugural convention

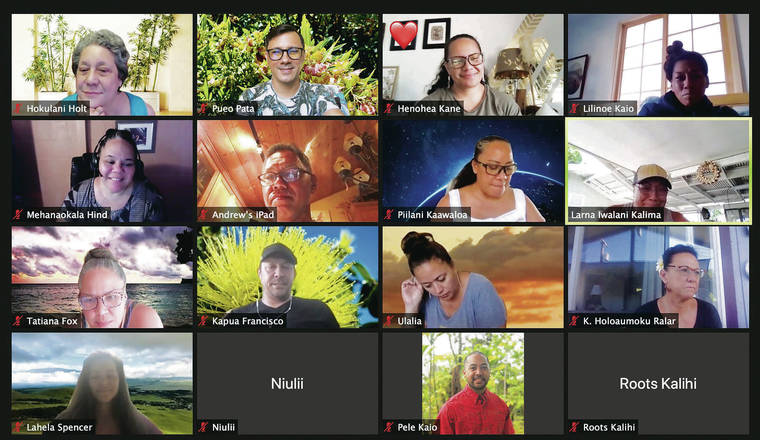

COURTESY CODY PUEO PATA

Kumu Hula Cody Pueo Pata’s Halau Hula ʻo ka Malama Mahilani performed a hula noho prior to the pandemic.

COURTESY CODY PUEO PATA

Kumu Hula Cody Pueo Pata’s Halau Hula ʻo ka Malama Mahilani performed prior to the pandemic.

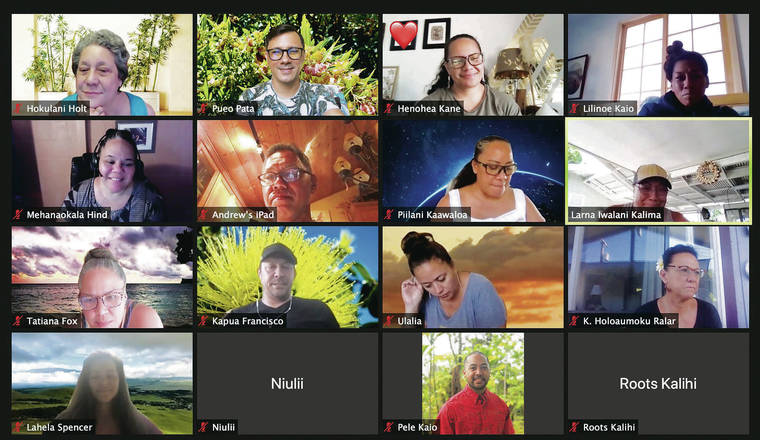

COURTESY CODY PUEO PATA

A screen image of a Huamakahikina Zoom meeting held in September.

Hokulani Holt has dedicated most of her life — nearly 50 years — to teaching hula. And during that time, the revered kumu said she and many other hula practitioners have seen things that are just not right: YouTube videos of people copying traditional dances and inappropriate chants that aren’t in Hawaiian, commercials advertising hula but actually showing Tahitian or other dances, individuals calling themselves kumu hula when they don’t have the cultural knowledge to claim the esteemed title, and over-commercialization of the art form.

The list goes on, she said.

Although these concerns have been brewing for years, Holt, 70, said it became even more evident last year when many kumu hula came together on Zoom to talk story. Although their initial discussions focused on the COVID- 19 pandemic, it led to deeper sessions about the state of hula and their collective concerns that the practice is being exploited and culturally misappropriated.

Now, more than 100 kumu are expected to come together to convene the first-of-its-kind Kupukalala Kumu Hula Convention to outline in a declaration the basic tenets of hula, such as defining the beloved cultural practice and identifying the meaning and responsibilities of a kumu.

Holt and eight other practitioners, known as the Leo Kahoa, or steering committee, have invited kumu hula from Hawaii and the mainland to attend the virtual event Aug. 21 and 22, and hope it will be the first of many more of these gatherings to come.

“In my opinion, hula is the only, or one of the very few, cultural practices that has gone unbroken since the beginning of Hawaiian time. We hold that as being a very important thing for us to take care of,” said Holt, kumu hula of Pa‘u O Hi‘iaka on Maui. “We’re hoping the declaration doesn’t become a piece of paper but that it can effect change.”

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

The larger organizing group, known as Huamakahikina, plans to present a draft of the declaration, which already has input from about 120 kumu hula, and ratify it at the convention. It currently includes a preamble of 25 bullet points that identify kumu as the sole authorities and beneficiaries of hula, how the practice should be presented to the world, who can teach it and how they will apply and implement the declaration’s tenets, said Holt and Cody Pueo Pata, member of the all-volunteer steering committee and kumu hula of Halau Hula ‘o ka Malama Mahilani.

Kumu hula Mehanaokala Hind of Na Pualei ‘O Likolehua, and a member of the steering committee who initially put out the call in August 2020 for kumu to come together during the pandemic, pointed out that it’s more important than ever to preserve and protect hula’s legacy, especially as older masters have died.

Hula has such a big reach, she said, that it’s important for the broader community to understand its intricacies. Although Hind acknowledged there will probably be some disagreements at the convention, she emphasized they are needed and welcome.

Pata said recent controversies involving Hawaiian culture and hula, including a Chicago restaurant owner trademarking the name “Aloha Poke” in 2018 that sparked discussions on legal protections for cultural intellectual property, and a former student trying to trademark her past kumu’s halau name in Japan in 2017, point to a larger problem.

Although many haumana (students) understand hula’s basic practices, he said putting this information into a formal document is needed to educate others who aren’t in the know.

“The declaration, in my opinion, is groundbreaking because kumu hula have never come together to formally and vocally protect our traditional profession. It’s momentous because we have different (schools) of hula that are usually competitive with each other, but because of COVID, the love we have for hula allowed us to associate in the most intimate and friendly ways,” Pata said. “This document is something that demonstrates our unity.”

Funded by Maui County, the Hawaii Community Foundation and other supporters, the convention is open to kumu hula only. Holt, director of the Ka Hikina O Ka La program for Native Hawaiians at the University of Hawaii Maui College, said that when people sign up, they are asked to provide their hula lineage and a list of teachers.

She said this information is vetted to ensure they have the proper credentials, training and experience to attend.

Holt added that “we in hula fully understand that we are responsible, not only for the cultural knowledge that we hold and transfer, but also we are absolutely responsible to those who gave us this knowledge. If people don’t have that feeling of responsibility to teachers, then they have no feeling of responsibility to their students.”

After the convention, Pata said they plan to present the declaration to the public and garner support from community leaders and government agencies, such as the Hawaiian civic clubs, the Hawaii Tourism Authority and others in the visitor industry, and policymakers.

By doing this, they hope to not only educate the community, but to also generate more funding for and interest in hula, such as the creation of a Hawaiian performing arts center or other spaces dedicated solely to the practice and the employment of more kumu hula at schools.

“We have an opportunity now to really put forward something that articulates what Hawaiian culture, and more specifically, what hula represents to our communities, to our islands, to our state and to the world,” Hind said. “There’s nothing like that out there. I’m happy that the rest of the world will have something to have in their hands and to chew on when it comes to hula. We’re ready to make things better.”

———

Jayna Omaye covers ethnic and cultural affairs and is a corps member with Report for America, a national service organization that places journalists in local newsrooms to report on undercovered issues and communities.