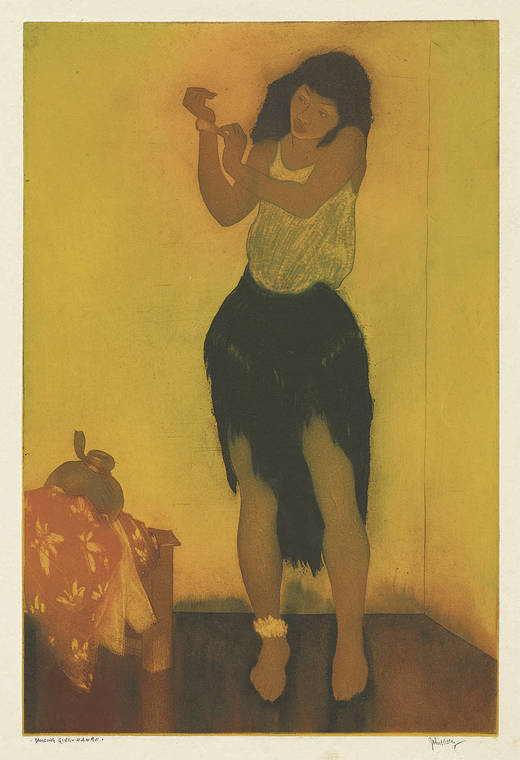

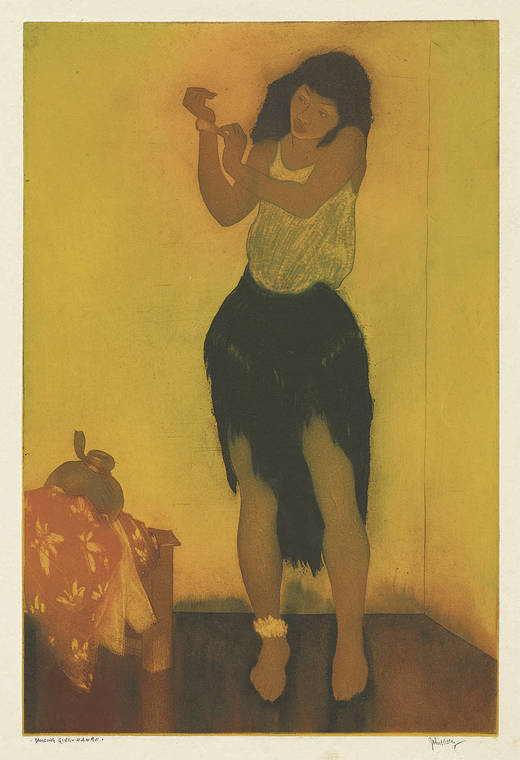

The artwork of John Kelly radiates with warmth — a warmth in the images themselves, which have a glow reminiscent of the Dutch masters, but also in the feelings for the people he portrayed, many of whom were neighbors from a nearby Hawaiian fishing village.

“Color is brilliant and softly glowing by turns,” wrote New York Times critic Howard Devree in a review of a 1940 show of Kelly’s works in New York. Devree praised the “sensitiveness of form” in one piece and the “strength, balance and poise” depicted in another, concluding his review with, “This is outstanding and novel work.”

More than 80 years later, those qualities and more will be on display in “Ho‘opuka — To Emerge: The Love of Hula,” an exhibition opening Tuesday at the Downtown Art Center. The show will feature about 15 of Kelly’s works, including paintings and various printing methods from lithographs and aquatints, all of them with hula as subject.

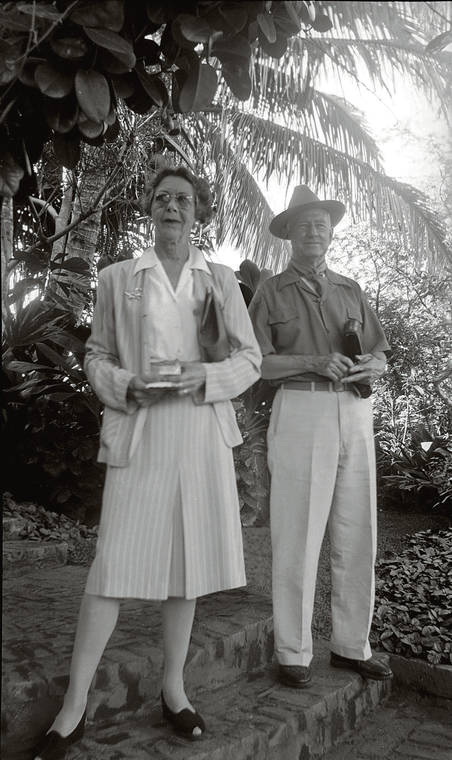

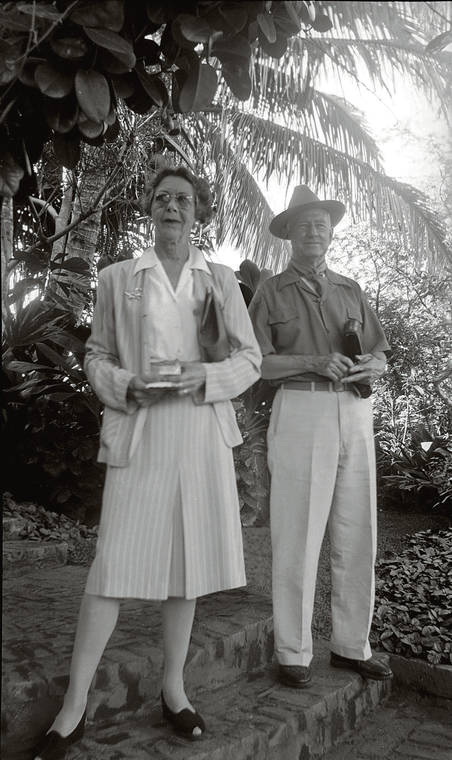

The show also will shine a better-late-then-never spotlight on John Kelly’s wife, Kate, who is best known for promoting his work but was a fine sculptor and photographer in her own right. Her vintage photographs of hula will be on display for the very first time in what promises to be just a taste of a treasure trove of historic images.

“The great thing is that we’re going to see work that’s never been seen before,” said Floyd Takeuchi, a photographer and journalist who curated the show. “We’re going to see a whole bunch of really fascinating photographs that (Kate Kelly) took, some of which were the basis for (John Kelly’s) prints — beautiful Hawaiian girls as models, but also ‘backyard hula,’ which is just fascinating to me.”

The Kellys came to Hawaii in 1923 when John Kelly, then an artist working in advertising, was hired for a commercial art project here. They fell in love with the islands and decided to stay.

John Kelly had grown up among Native American tribes in Arizona, which Takeuchi believes led them to form a particular attachment for Indigenous people of various cultures. “That’s very different from what you would expect of the well-to-do class at that time here,” he said.

The family eventually built a home, which also became their studio, in Black Point, then sparsely populated with just a few homes and fishing villages. John Kelly got a day job as the art director for the Honolulu Star-Bulletin while feverishly pursuing a career as an independent artist, which is where Kate Kelly played her instrumental role. She studied printmaking at the University of Hawaii and taught it to John; later, she organized shows of his work locally and on the mainland.

John Kelly himself did little to promote his art.

“He didn’t care,” said Cha Smith, a former environmental advocate who now manages the Kelly estate along with Colleen Kelly, the Kellys’ granddaughter. “He was like, ‘I’m not going out there, I’m not doing it.’ He barely went to openings here.”

Just as importantly, Kate Kelly found people to model for her husband and took photos that he used to create his engravings and prints. While many of those photos are well-known, there are about 1,500 photos of daily life that Smith has been digitizing and plans to display someday.

It is apparent from these photos, as well as photos of hula, that she had an affinity for the Native Hawaiian people and their traditional dance, Smith said.

“You can really tell her appreciation for hula,” Smith said, adding that Kate Kelly joined a halau led by Antone Ka‘oo, a revered kumu hula. Smith said the photos in the exhibition will show informal dances, “the kind of hula that people did for each other, at picnics, or just as an exchange for each other.”

Thanks to Kate Kelly’s effort, her husband’s art began to garner critical acclaim. “Kelly does … everything the camera can do, plus that mysterious ‘something’ that comes out of the emotions of the artist that heightens, intensifies and creates a ‘personality’ above and beyond nature,” wrote Chicago Daily News art critic C.J. Bulliet, in a comment about “Kanani,” a black-and-white etching of a young woman that was displayed in Chicago in 1937.

Matson commissioned a series of John Kelly’s pieces to use as menu covers, which passengers were encouraged to keep as souvenirs. Taking advantage of the connection, Kate Kelly would meet cruise ships at Aloha Tower to bring celebrity clients to Black Point to look at his work.

“There were definitely movie stars that would come,” Smith said, naming Humphrey Bogart and Rita Hayworth as two who were rumored to have visited the home. While it is unknown whether they bought anything, John Kelly’s work is held in significant collections at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Fogg Museum at Harvard University and the De Young Museum in San Francisco.

Colleen Kelly, who still lives in her grandparents’ home, has vague memories of her grandfather, but even those memories are testament to his work ethic. His elegant, detailed prints were created using an exacting process that required a combination of precision skills.

“He was always busy with his art,” said Colleen Kelly, a retired Kaiser employee and the daughter of famed waterman John M. Kelly of the Save Our Surf movement. “When we would come to visit, and after we moved in, Grandpa was always in this other room (his studio) working. … But I look at his work and I think, ‘No wonder I couldn’t get to know him.’ This takes hours and hours of dedication.”

IN ADDITION to oil paintings and aquatints, the show at the Downtown Art Center will feature two of John Kelly’s watercolors, which show Waikiki street scenes. “Those have never been shown before,” Takeuchi said. “I was able to convince myself to put those in the show because the morning scene has a hula dancer in it.”

The Kellys’ masterpieces will form the centerpiece of the exhibition, which also will include works by 10 other artists. Many of them created new works for the exhibition, said Takeuchi, who is contributing photos stemming from a two-year project photographing Halau Na Mamo O Pu‘uanahulu, kumu hula Sonny Ching’s halau.

One of the artists, Nancy Vilhauer, is well-known for her paintings and etchings of hula. She likes to portray the behind-the-scenes moments in hula, working off photos she takes of hula festivals moments before dancers are about to perform.

“I really feel like those little in-between moments that don’t get recorded by most people is really an important part of hula,” she said. “It does seem like sort of an intimate thing — mothers helping their daughters and the young dancers listening to the kumu with great reverence before they go onstage.”

Takeuchi was also enthusiastic about up-and-coming artist Nalamakuikapo Ahsing, calling his large-format pieces “stunning concepts for how he visualizes the influence of his culture.”

Other artists featured are Kumu Hula Auli‘i Mitchell, a practitioner of hula ki‘i, or hula with puppets; sculptor Jackie Mild Lau; printer Margo Vitarelli; photographer Jordan Kamuela Gestrich; multimedia artists Sandra Blazel and Karen Lucas; and artist Lauren Okano, whose abstract approach to hula represents “our commitment to approach the subject from as many different ways as possible,” Takeuchi said.

Takeuchi organized the show based on the overarching theme of “love for the dance and the culture,” he said.

“I think it’s going to be a very dynamic and very different type of art show.”

—

“Ho‘opuka — To Emerge: The Love of Hula”

>> Where: Downtown Art Center, 1041 Nuuanu Ave., second floor

>> When: Open Tuesday through Aug. 28; a First Friday reception will be held 5-8 p.m. Friday

>> Gallery hours: 11 a.m.-6 p.m. Wednesdays to Sundays

>> Cost: Free

>> Info: 773-7339, downtownarthi.org Opens in a new tab

Correction: An earlier version of this story misspelled the exhibit's name, "Ho‘opuka — To Emerge: The Love of Hula."