The state Department of Labor and Industrial Relations found itself in an undeniably precarious position at the start of this epic pandemic and economic meltdown — although none of that is an excuse for what is now a deficit in communication with its increasingly desperate clientele.

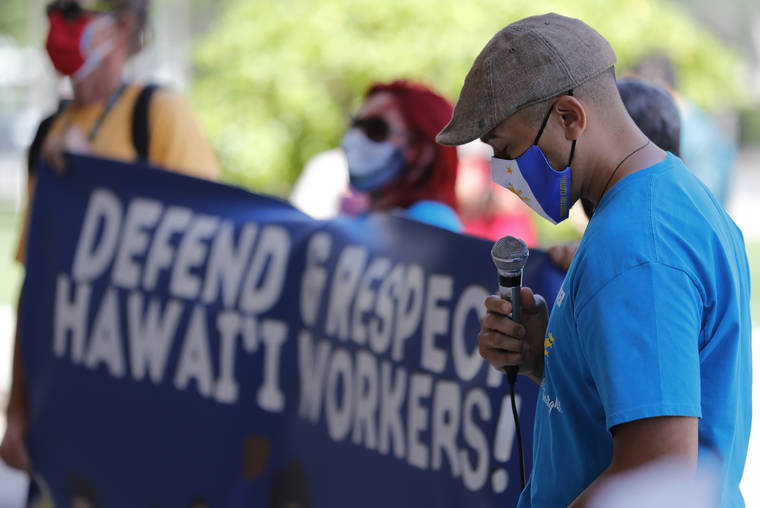

Mounting anger among the unemployment insurance claimants culminated last week in a rally at the state Capitol. So far, there’s been little action within the building, from either the lawmaking chambers or the governor’s top-floor office, to chart a course out of a bureaucratic morass, a workload that has overwhelmed the system meant to help them.

In this age of remote conferencing, there are ways to bridge this divide, to give the claimants a voice. And above all, Gov. David Ige and his team at the DLIR, must ensure that enough personnel resources are brought to bear on this public-service dysfunction.

Right from the start, breakdown was always the likely result of a toxic mix of circumstances. Like most states, Hawaii’s unemployment insurance deployment was encumbered by an antiquated computer system wholly incompetent for the job at hand. Mistakes have been made in managing the claims, which included a fair amount of fraud as well as legitimate, if complicated, claims.

Unlike most states, though, this one had just shot from the lowest unemployment rate to the highest in the nation. The sudden shuttering of the tourism industry, in a work landscape dominated by all the jobs connected to it, produced a predictable flood of layoffs and business closures.

There was a deluge of new filings for unemployment onto an agency ill-equipped to handle them. A new information technology system was in development as coronavirus appeared in the islands, but it won’t be deployed for another 18 months.

The solution lies in prioritizing the problem and deploying the staff to whittle down the claims, said Peter Yee, whose car-rental job went on ice when the shutdowns happened and has been following the crisis ever since.

Yee moderates a Facebook group of 26,000 Hawaii unemployment claimants and advises a separate one just as large, filled with jobless local workers who speak little English. Back at the pandemic’s start in March and April, he said, there were already reports of some 70,000 complex claims, each taking 50 minutes, on average, for a crew of only 30 examiners to address. The shortfall only worsened over time.

“The count of examiners never got that high,” Yee added. ”They should have a workable ratio of examiners to claims.”

An insurmountable backlog grew from there but nearly a year later, not enough resources were ever devoted to cracking the tough cases. What’s worse, those who may have been unjustly caught in this jam have had little luck breaking through, and now DLIR has been unwilling to face an angry crowd directly.

During a Feb. 19 interview on the Honolulu Star-Advertiser’s “Spotlight Hawaii” webcast, DLIR director Anne Perreira-Eustaquio said the department is assembling a team of examiners to adjudicate some of the problem cases. More information about the ratio of staff to cases is needed.

Further, Ige said in a webcast last week that he has the ability under emergency powers to redirect existing staff to tackle the problems as well. So why hasn’t he? Those who have been waiting for nearly a year to receive unemployment benefits — or, at a minimum, a status report on their cases — are desperately waiting for the governor to step up.

A deadline is looming for the state to provide guidance for those in the first-year wave of filers whose cases are unsettled. Their claims are due to expire, starting in a few weeks. How should they proceed at this point?

Perreira-Eustaquio also noted that DLIR processed 30,000 claims for the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) extension, those that did not have any outstanding questions. But there are in excess of 30,000 more that do have issues: How far down the road will DLIR be kicking the can?

These are just sample queries that deserve answers, and although Perreira-Eustaquio recommended phoning the Hawaii Convention Center call center, a lot of people have tried that for the past year, with little to no resolution.

That’s why about 200 claimants turned up on Wednesday for a march from DLIR to the Capitol. They rightly want access to unemployment offices, which have been closed to the public due to the pandemic. The director has said staff can’t handle the overwhelming demand in person and needs first to get workload reduced.

Fine. But some triage is in order — those who have been waiting for many months should be advanced in the queue.

And in this technological age, there are communication platforms that haven’t been tried. A webinar could summarize key information for many people and provide a means of applying for an appointment, which itself could be done virtually.

However it happens, it’s the duty of public servants to deliver services — and simply restricting access does not relieve them of that duty.