Rearview Mirror: Espionage and internment among the themes that emerged in WWII

COURTESY PHOTO

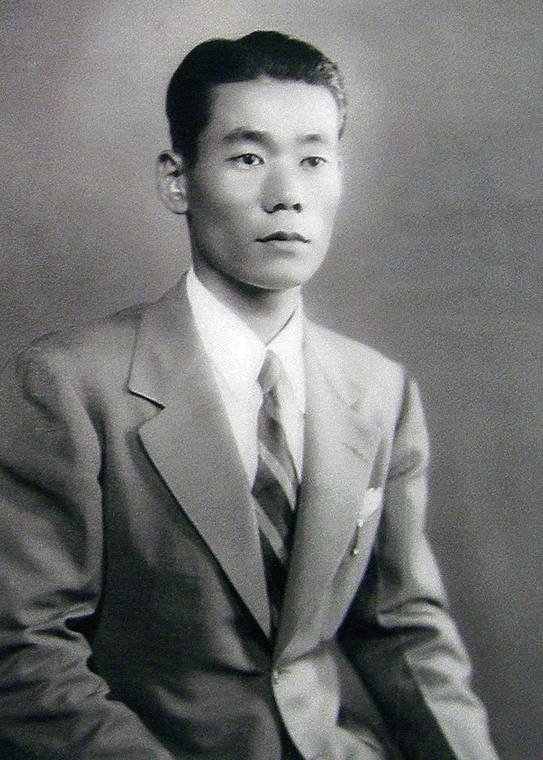

Hung Wai Ching

COURTESY PHOTO

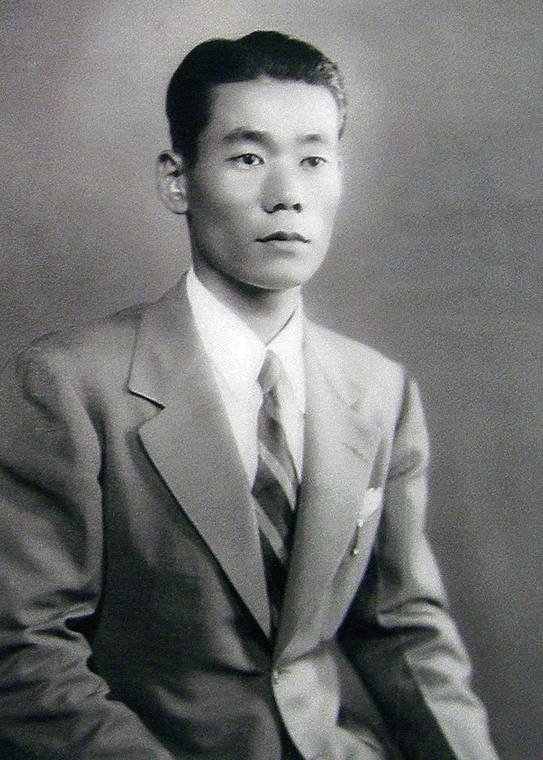

Robert Shivers

STAR-ADVERTISER

John Burns

U.S. NAVAL INSTITUTE

Takeo Yoshikawa

Following the Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Hawaii, the War Department evacuated all 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry from the west coast to internment camps.

There were 160,000 persons of Japanese ancestry in Hawaii, and they were much closer to the war, yet less than 1% of them were interned. Why?

Much of it had to do with police Capt. John Burns and FBI agent Robert Shivers.

There was a representative of the Navy, FBI and police department that looked at possible cases of internment, John Burns’ son, James, told me many years ago.

“My father said the Navy guy always voted for internment. The FBI guy and my dad would only vote for internment if there was evidence of espionage, and there never was. So it was typically a 2-1 vote against internment.”

Shivers had come to Hawaii to run the FBI office in 1939, A.A. “Bud” Smyser wrote in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin in 1979.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

The first Asian he and his wife, Corinne, had any close contact with was Sue Isonaga from Maui. She lived in the Shivers’ Black Point home and worked as a cafeteria manager at McKinley High School.

Isonaga said Shivers was kind, understanding, and always ready to help whoever needed it. He was a “man with a big, big heart. One in a million.”

Shivers asked if loyalty to Japan was taught in local language skills, and she replied “never.”

He credited University of Hawaii Regent Charles Hemenway for helping him understand the complex racial conditions in Hawaii.

Because there was never any act of sabotage in Hawaii, he and John Burns were able to stand up to those who argued for mass internment. Less than 1%, primarily kibei, born in the U.S. but sent to Japan for schooling or business, Shinto priests, Japanese consular officials and a few others were interned.

Shivers told Isonaga after the war that he couldn’t stand the idea of ruining the lives of thousands of loyal Americans of Japanese ancestry by interning them.

Souvenir

To help preserve the interracial harmony in Hawaii during and after the war, Shivers turned to Hung Wai Ching, the first Asian executive secretary of the Atherton YMCA at UH.

Shivers thought Ching could do that as a Chinese man whose country had been invaded by Japan. He was the founder of the Varsity Victory Volunteers, which evolved into the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

Ching met with Eleanor Roosevelt at the White House on May 6, 1943, to report on Hawaii’s racial issues.

Roosevelt had him return to the White House two days later, on a Sunday, to speak directly with President Franklin Roosevelt about conditions in Hawaii as Ching saw them.

Roosevelt was in shirtsleeves at his desk in his upstairs study and they talked alone for 40 minutes.

Ching stressed that things were being handled well in the islands. He praised the decisions to avoid mass internment and allow soldiers of Japanese ancestry into combat.

At one point in the conversation, Ching took out a cigarette and the president leaned over to light it for him. Ching decided to save it as a souvenir. Not really thinking, he put it in his coat pocket, still glowing.

The burning cigarette ruined his suit, but he had the souvenir!

The real Pearl Harbor spy

There was spying in Hawaii leading up to World War II, we know, so who did it? It turns out the Japanese had just one man, Takeo Yoshikawa.

Yoshikawa (1912-1993) graduated at the top of his class from the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy in 1929. In 1941 he was sent as vice consul to the Japanese consulate in Hawaii, said Ron Laytner, who interviewed him 30 years after the war in 1976.

The Americans were very foolish, Yoshikawa told him. “As a diplomat, I could move about the islands. No one bothered me. I often rented small planes at the John Rodgers Airport in Honolulu and flew around U.S. installations making observations. I never took notes or drew maps. I kept everything in my head.”

Yoshikawa was a good swimmer, and swam in Pearl Harbor. No one bothered him.

“I completely surveyed the harbor installations. And my favorite viewing place,” recalled Yoshikawa, “was a lovely Japanese teahouse overlooking the harbor.” It was called Shunchoro and was in Alewa Heights. In 1957 it changed its name to Natsunoya, and it is the last teahouse on Oahu.

Yoshikawa tried to recruit local Japanese, Laytner wrote, but all professed loyalty to the U.S., leaving him to work alone.

“I knew what ships were in, how heavily they were loaded, who their officers were, and what supplies were on board,” Yoshikawa said.

“The trusting young officers who visited the teahouse told the girls there everything. And everything they didn’t reveal I found out by giving rides to hitchhiking American sailors and pumping them for information.”

For a while Yoshikawa posed as a Filipino and washed dishes in the American naval officers’ club, listening to their conversations.

As Dec. 7, 1941, grew closer, Yoshikawa handed a Japanese courier answers to 97 intelligence questions asked by Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto concerning ships, planes and personnel at Pearl Harbor.

Yoshikawa reported that most ships were at anchor in Pearl Harbor on Sundays, so the attack was planned for that day of the week.

Yoshikawa was eating breakfast and still sleepy when the first bombs began to fall before 8 a.m.

“The consul and I listened to the shortwave radio bringing the news from Tokyo,” he said. They heard the secret attack code. “East Wind, Rain,” the Japanese announcer said twice very slowly during the forecast. This meant that Japan had decided on war with the United States, the spy revealed.

Yoshikawa and the consul shook hands. The attack was on. They ran into their offices and began burning code books and secret diplomatic communications.

At 8:30 a.m. police showed up, followed by the FBI, putting them under arrest.

Yoshikawa and other diplomats were shipped to New York City before being sent back to Japan in a diplomat- prisoner exchange in August 1942.

When he got home, Yoshikawa met a woman and married. He continued to work with Japanese intelligence.

In 1955, Yoshikawa opened a candy business. But people knew who he was. They wouldn’t buy from a spy whose country had lost the war, he said.

“They even blamed me for the atomic bomb,” he declared with tears in his eyes. And he might have starved over the years if his loyal wife hadn’t supported him by selling insurance.

“I have been wiped clean from Japanese history,” he told Laytner, who found him living on the island of Shikoku south of Tokyo.

“Five years ago, when I applied for a pension, they said they never heard of me. When I told them of my espionage assignment, of the long years working to become an expert on the American Navy and of my dangerous mission in Honolulu, they were without sympathy. They told me Japan never spied on anyone.”

“My wife alone shows me great respect,” said the former spy. “Every day she bows to me. She knows I am a man of history.”

For more information on the 75th anniversary celebration of the end of World War II visit 808ne.ws/ 3fDkJ7Q Opens in a new tab.

Bob Sigall is the author of the five “The Companies We Keep” books. Email him your comments or suggestions at Sigall@Yahoo.com.