The $50 million Topgolf project has stalled (“Topgolf hits pause on $50M Ala Wai plan,” Star-Advertiser, July 29). Now is the time to return the Ala Wai Golf Course to its predevelopment state as an extensive wetland, flooded-field agricultural system, and natural retention basin to manage flooding. Doing so will be an effective step forward in building resiliency to sea level rise.

Models show the golf course as one of the first places to flood as a result of sea level rise. This is demonstrated several times a year as extreme tides, which are growing in frequency, overflow the banks of the Ala Wai Canal. Makai portions of the golf course hold ponds of standing water for hours after hard rains. At high tide, there is essentially no drainage from those lands other than what we have engineered.

Guidance from the Honolulu Climate Change Commission urges the mayor, the City Council, and the people of the City and County to prepare for sea level rise now. Modeling indicates that between the mid-2030s and mid-2040s, king tides reaching 20 inches above present high tide go from occurring zero times annually to roughly 50 events per year. This is higher than anything we’ve experienced to date and constitutes a massive and rapid change. This will flood large portions of the golf course at high tide and, at those times, render the golf course unusable.

Would you risk $50 million on a project that is ultimately doomed only one to two decades after building it? Let’s follow the Mayor’s Directive No. 18-01, which directs all city departments and agencies to minimize risks from, and adapt to, the impacts of climate change and sea level rise.

Converting the golf course into a wetland is a quadruple win. A nature- based solution will have enormous flood control value; it will help cleanse polluted runoff heading to the Ala Wai; it will increase natural habitat for indigenous water birds and plants; and it will be a recreational destination as a public park.

National statistics related to golf show a general, steady decline in the number of players in America. Over the last decade or so, around 20 golf courses across the U.S. have been turned into public parks. Miami Beach, a community aggressively pursuing adaptation strategies to mitigate sea level rise, is currently proposing to convert a popular city-owned golf course into a wetland eco-district.

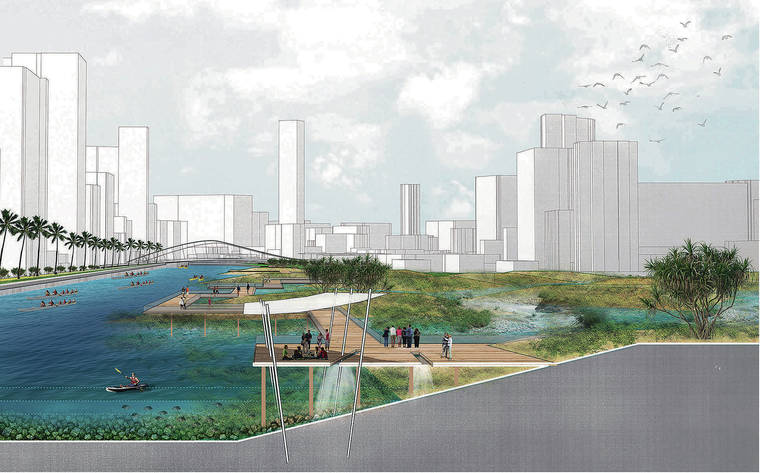

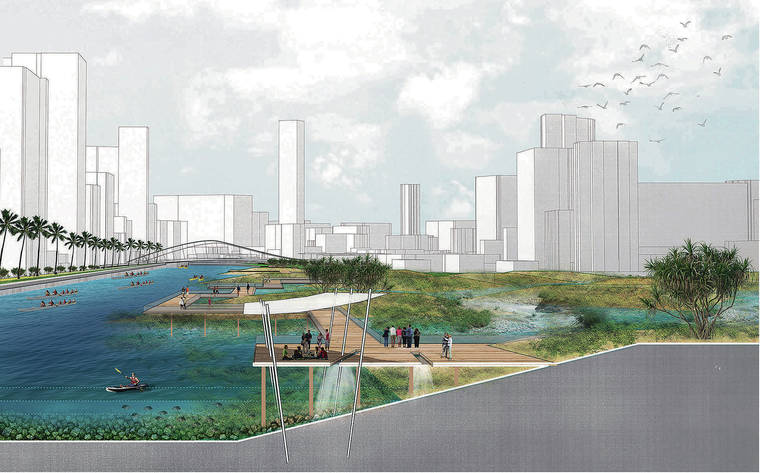

The conceptual rendering here illustrates how an elevated pedestrian promenade along the mauka edge of the Ala Wai could serve as an attractive public open space amenity that improves connectivity while allowing for the unhindered flow of water and protecting the proposed wetland habitat from disturbances by humans and pets.

Less prone to flooding, the golf course’s Date Street and Kapahulu edges could be envisioned — through thoughtful design — as landscaped, multipurpose landforms that incorporate elements of locale-appropriate, sustainable and shady, urban mixed-use development. In this scenario, the proposed Ala Wai wetlands would become part of the new development’s off-grid water treatment and food system.

Converting the Ala Wai Golf Course landscape into a large-scale urban sponge and ecological priority zone would significantly increase the area’s overall biodiversity and provide numerous other ecosystem services. We know that nature-based solutions, such as living shorelines, act as effective buffers and “soft” defense mechanisms against sea level rise and flooding (vs. hardened solutions such as levees that are prone to failure). Wetlands facilitate adaptation over time by embracing variable and dynamic conditions rather than preventing them.

The golf course’s generous dimensions allow for a patchwork of large, undisturbed marsh habitats and fields of wetland agricultural systems such as the kalo lo‘i that characterized the area before it became a golf course. The incorporation of a modern-day urban taro farm and fish or shrimp ponds would contribute to reviving the site’s cultural significance and provide educational opportunities while offsetting some of the cost associated with maintaining the wetland.

This is the time for Honolulu to be proactive and bold in positioning itself among other resilient coastal cities in the world, many of whom are planning and implementing large-scale coastal green infrastructure solutions like the one proposed here. Converting the outdated Ala Wai Golf Course into a model urban wetland would merge the seemingly conflicting goals of ecological function and urban place-making into a mutually beneficial, resilient relationship.

Charles “Chip” Fletcher, a Honolulu Climate Change commissioner, is associate dean and professor in the University of Hawaii-Manoa School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology; Judith Stilgenbauer is professor of landscape architecture at the UH School of Architecture.