Wahiawa pediatrician Lucio Pascua recalls being ‘trapped’ in COVID-19 ‘void’

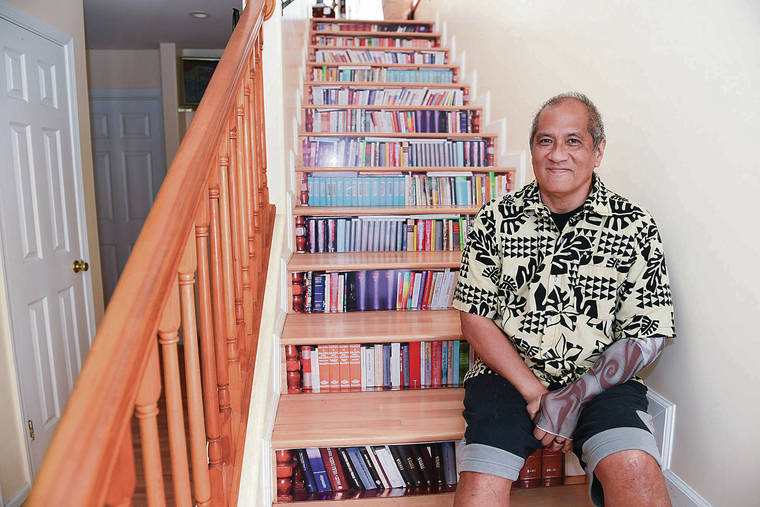

BRUCE ASATO / BASATO@STARADVERTISER.COM

Dr. Lucio Pascua fell ill with the coronavirus in March after a trip to New Jersey and New York. He was on a ventilator for 10 days before finally recovering. Pascua sits on his stairway with books stored behind.

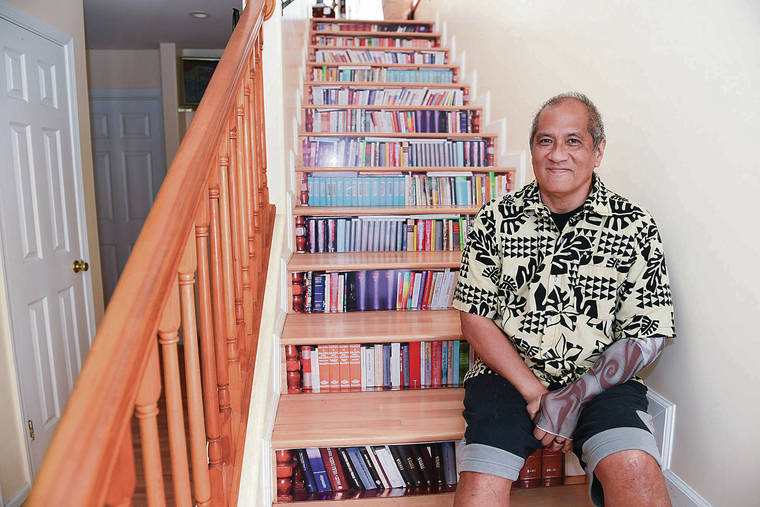

BRUCE ASATO / BASATO@STARADVERTISER.COM

Dr. Lucio Pascua fell ill with COVID-19 in March after a trip to New Jersey and New York for his daughter’s engagement party. He was on a ventilator for 10 days and developed sepsis — blood poisoning — before finally recovering. Pascua stands in his front yard.

There were moments of sheer terror and bizarre hallucinations, then spurts of rational thoughts racing through Dr. Lucio Pascua’s mind as he lay paralyzed on life support battling the new coronavirus.

But it was one lyric in a church choir song, “Be not afraid,” that Pascua says was the turning point in his recovery from COVID-19.

“Out of everything I could have thought — resignation, resentment — suddenly I remembered, ‘Be not afraid,’ and it was like hope that you’re not done here,” Pascua, 60, told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser. “At that point in time it gave me comfort and bravery.”

It was a song the Wahiawa Health pediatrician, a 25-year choir director at his church, intended to sing on Easter. Instead, he was on a ventilator for 10 days and had developed sepsis — poisoning of the blood — after contracting COVID-19 while on a trip to New Jersey in March for his daughter’s engagement party.

The longtime doctor, who goes by Leo, said his family ventured for five hours into New York City for pizza and to visit a piano bar right before officials locked down the city, which became the epicenter of COVID-19 cases in America. The United States has surpassed 100,000 deaths due to the coronavirus.

Pascua started feeling ill while flying back home and was admitted into The Queen’s Medical Center on March 28. By the time he entered the hospital, his oxygen levels had fallen to 84%, prompting doctors to immediately place him in the ICU and intubate him shortly thereafter.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

Unlike many COVID-19 survivors, Pascua vividly remembers being trapped in a “void” while in a coma and hearing the voices of the health care workers surrounding him.

“This was a situation I thought was unthinkable. You lose your sense of time, but you do not lose rationality, your values and how you feel about things,” Pascua said, describing the situation as “endless anxiety.” “All you want is your freedom back. You get some disorientation, you start to feel some panic, rationally you think … ‘I’m going to do whatever I can to wake myself up.’ But you can’t. It’s like being in your own personal suspense thriller that doesn’t end.”

Pascua said he tried to telepathically call upon his wife and two grown children.

“I remember feeling fearful at that point trying to almost telepath my wife and kids, saying, ‘This is what’s going to happen. You’re going to get a call from a physician who’s explaining to you what situation your dad is in. You must ask them every question you want to ask even if it scares you.’”

At one point he recalls hallucinating, thinking he was in the helm of a spaceship.

“You’re in an environment that’s unfamiliar to you. Your deepest fears are in the same room as rational thought,” he said. “If you’re having a really frightening dream, you can wake up and see where you are. In this case, even when you’re frightened, you can’t do that.”

He lost his sense of physical orientation and gravity, all the while trying to problem-solve his way out of the situation.

“Even though you’re anesthetized, you’re not fully unconscious. You’re intermittently thinking and have an emotional presence. It’s like you’re in a dream,” he said. “You have to be your own best friend even in the void. You can either freak yourself out or think good thoughts or remember what the recipe is for the fried rice you made on Sunday.”

His wife, Atina, 56, and children couldn’t visit him in the hospital, which was closed to visitors due to the pandemic. Not being able to physically be there, especially before her husband was put on a ventilator in respiratory distress, was the worst part, she said.

“That made us feel really bad. You vacillate between trying to stay real positive, and you are fearful of the worst, and then you cling to every single word that the medical staff is telling you and that the physicians are saying,” she said. “I had to have a real trust of the medical system in the state of Hawaii.”

The doctors and nurses at Queen’s “did as much as they could to make sure that our family was made aware of his condition on a daily basis,” she said.

“They were very compassionate, very flexible, just willing to do whatever they could to reassure the family,” she said.

But it was also her husband’s positive mindset, resolve and “fighting spirit” that helped him pull through the life-threatening ordeal, she said.

“I think that had a lot to do with the way he journeyed onto the respirator and when he came out of it as well,” Atina said. “Before they put him on the ventilator, he said to all of us, ‘Don’t worry, it’ll be OK.’ He just has, as they say, a zest for life. He also has a very positive attitude and great deal of faith. I also would say that through prayer and science together that a miracle occurred.”

After nearly a month Pascua tested negative April 26 for COVID-19 and recently started treating patients via telehealth. He also has begun lifting weights to regain his strength, and on a recent Sunday was able to sing a solo from the back of his church.

“In terms of recovering from emotional despair and from this feeling of paralysis and uncertainty, I’m going to (attribute that to faith),” he said. “Even when intubated on a ventilator, you have that choice whether to stay faithful or not. You can choose what to think, you can choose what to believe. I thought I will accept that as a presence, and sure enough, here I am.”