Column: Rachel Handlin proves her public-school naysayers wrong

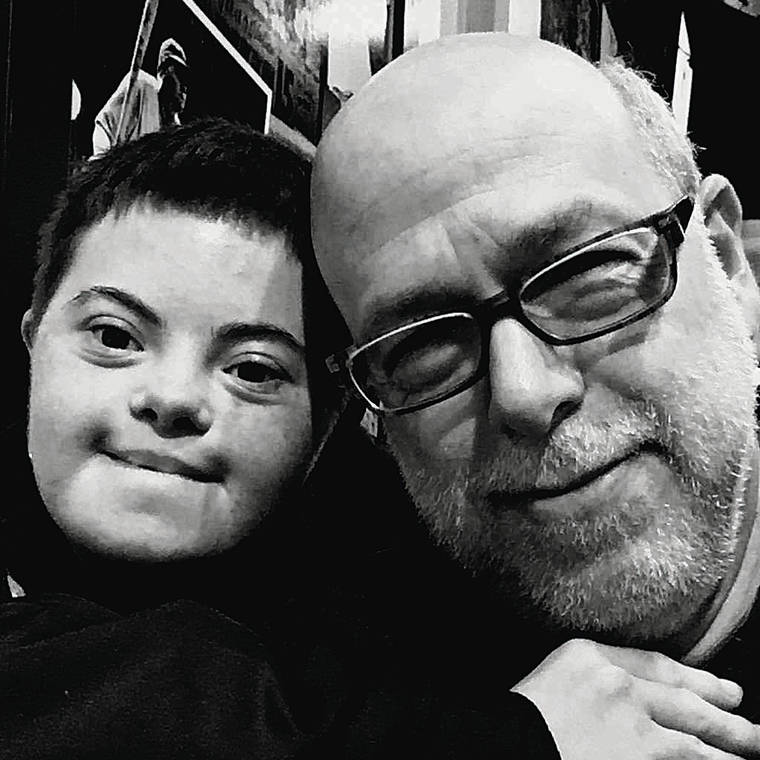

Jay Handlin and his daughter, Rachel

Nearly 2 million U.S. college students will earn bachelor’s degrees this year. COVID-19 is robbing them of caps and gowns, commencement ceremonies, graduation parties. That’s a loss for all. But some graduations were harder accomplished than others. I want to talk about one: my daughter Rachel’s. She’s earned it.

Unlike nearly every other graduate, Rachel has Down syndrome. Her attaining a regular college degree is beyond rare. My wife and I have scoured the internet for others with Down’s who earned 2- or 4-year degrees. We’ve discovered 10. We may have missed a few, but by our count, Rachel will be the 11th. In the whole world. Ever. In the global Down syndrome population, college degree recipients are literally one in a million.

Many folks will see Rachel as an aberration. Oh, they’ll say, she’s one of the high-functioning ones. Please don’t say that. Functioning labels are just lazy excuses used to justify an unfair status quo. Lower achievement likelier stems from lack of opportunity, not from some innate functioning level.

Down syndrome is an intellectual disability. It makes learning harder, not impossible. Imagine if a child — any child — was born, and no one did anything to encourage, support, educate her. She might have endless potential, but she’d probably never find it. Babies are helpless, blank slates. For many years, infants, toddlers, children depend on others to provide them what they need to learn and grow. Yet overwhelmingly, society gives the least help to those who need it most, and is content to leave their slates blank.

On May 15, Rachel Handlin will earn her Bachelor of Fine Arts Degree in photography and media from the prestigious California Institute of the Arts. First and foremost, she’s reaching that milestone because of her talents and abilities, her unique vision and endless hard work. But to get there, she needed support from an incredible team: parents, therapists, aides, teachers, tutors, friends.

Not everyone has helped; many have hindered. In California, the principal wanted Rachel to attend only recess and P.E. with the general education class. We refused. Backed by an education rights lawyer, we insisted she be fully included. Over time, her school came around and embraced Rachel. Then she moved to Hawaii in 2009, entering 7th grade at a lauded public middle school. The administrators, most teachers and Department of Education were antagonistic. They wanted her in the special ed room, where other students with Down syndrome did “math” assignments like drawing pictures of beans in a jar. We said no. Promised accommodations never materialized. Students in her general ed classes pointedly ignored her. We asked for help, got none.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

To save Rachel’s self-esteem, we moved her to private school, with administrators and teachers willing to break the mold and practice real inclusion. Academy of the Pacific was a haven while it lasted — until DOE pulled funding for students entitled to it under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. After AOP folded, St. Andrew’s Priory leaders showed vision and principle DOE lacked. Rachel completed 11th and 12th grades there, graduated with honors in 2015, and will be a proud Priory Girl forever.

Not everyone with Down syndrome will attend and graduate from college. That makes them just like the rest of the population. What they deserve, like everybody, is the help to discover and maximize their abilities. Supported, kids with Down’s can — should — be learning in the general ed classroom. Eventually, there should be hundreds, even thousands of Rachels.

To Rachel’s educational allies, mahalo. To everyone who set needless obstacles in her path, you were wrong, and we told you so.

Jay Handlin is a business and intellectual property litigator who has lived and lawyered in New York, California and Hawaii.