Rearview Mirror: Missionaries made their mark in Hawaii 2 centuries ago

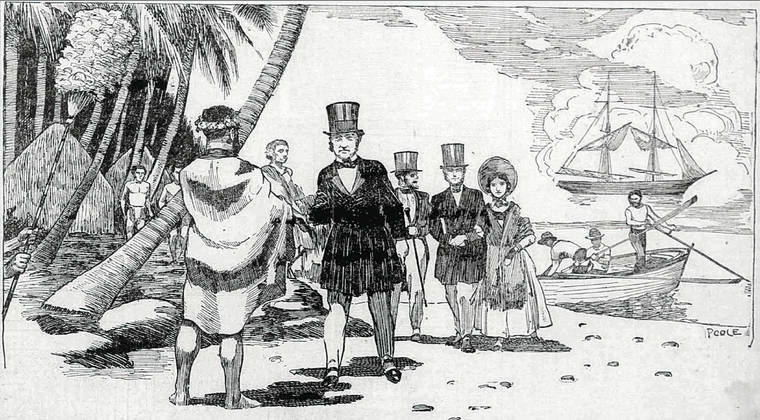

ILLUSTRATION BY JOHN C. POOLE, 1924 / HONOLULU STAR-ADVERTISER

The first group of American missionaries arrived 200 years ago and received Kamehameha II’s permission to teach, preach and publish in Hawaii.

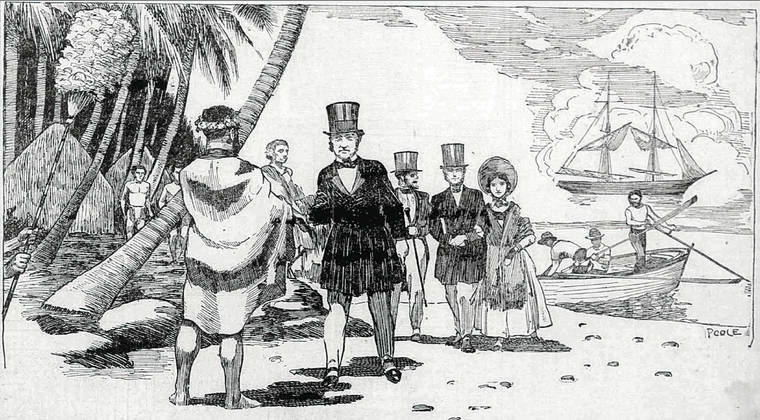

ILLUSTRATION BY JOHN C. POOLE, 1924 / HONOLULU STAR-ADVERTISER

Within two years the missionaries had learned Hawaiian, turned it into a written language and began teaching it to more than half of the adults in the kingdom.

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES

Henry Opukaha‘ia traveled to the mainland in 1807 and inspired the first of 12 companies of American missionaries to come to Hawaii.

Last month marked the 200th anniversary of the arrival of the first company of missionaries to Hawaii from Boston.

In researching this article, I learned a few things I hadn’t known previously.

The brig Thaddeus contained just two ministers of the 14 adults, and four people aboard were young Hawaiian men who came as educators and translators. One was the son of the king of Kauai and Niihau.

Besides the 20 crew, the passengers were the Rev. Hiram and Sybil Bingham, the Rev. Asa and Lucy Thurston; teachers Samuel and Mercy Whitney, and Samuel and Nancy Wells Ruggles; farmer Daniel and Jerusha Chamberlain and their five children; Dr. Thomas and Lucia Holman; and printers Elisha and Maria Loomis.

The Hawaiians were John Honolii, Thomas Hopu, William Kanui and Prince George “Humehume,” son of Kaumualii, the king of Kauai.

Humehume was not a member of the mission, but accompanied them on the Thaddeus. As a 6-year-old child in 1804, he had been sent to America for an education.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

By 1810, historian C.T. Starr estimates about 60 Hawaiians were living in America.

The four Hawaiians aboard the Thaddeus had enlisted in the U.S. Navy and served in the War of 1812. Leaving the Navy, they returned to Boston, and for a time attended the Cornwall school in Connecticut.

Why did the missionaries choose Hawaii? It was because another young Hawaiian, Henry Opukaha‘ia, had traveled to the mainland in 1807.

He found himself in Boston and became a Christian. He asked church leaders there to reach out to the people of Hawaii so that they could hear the good news.

Unfortunately, he died in 1818 of typhus, but his enthusiasm inspired the first of 12 companies of American missionaries to make the arduous journey.

The Thaddeus spent over 160 days at sea before arriving near Kohala on the Big Island on March 30, 1820.

A rowboat was sent ashore “to make inquiry of the inhabitants respecting the state of the islands and the residence of the king,” Howard D. Case wrote in the Honolulu Star-Bulletin in 1924.

Kamehameha I had died the year before, they were told, and his son, Liholiho, had recently taken the throne. Less than a year earlier, he had abolished the ancient kapu system of the kingdom, creating a vacuum for the missionaries to spread their religious beliefs.

Kalanimoku, the prime minister, was not far away in Kawaihae, and the Thaddeus sailed there.

Islanders in canoes came paddling out. Lucy Thurston leaned out one of the cabin windows and was given a banana.

She handed out some biscuits to the Hawaiians. “Wahine maikai” (good woman), they said.

“Wahine” — one of the many Hawaiian words she understood, from daily shipboard lessons — she replied.

Kalanimoku and his retinue came out in a double canoe propelled by a score of athletic men. Kahilis waved, and a canopy protected the chiefs from the sun. In contrast with the people whom the missionaries had seen in the morning, the chiefs were well clad.

The Rev. Hiram Bingham wrote that Kalanimoku wore “a white dimity (lightweight cotton) roundabout, a black silk vest, yellow Nankeen pants (yellow cotton), shoes, white cotton hose, plaid cravat, and fur hat.” Lucy Thurston was impressed and surprised by his dignity and culture, he noted.

Kalanimoku shook hands with the men and bowed to the women, saying “aloha” to each. He stayed aboard, chatted and dined with the missionaries.

The Hawaiian queens had obtained cloth from traders who, as best as they could, explained garment construction. But it took only a glance to see the missionary women had skills far beyond theirs.

Queen Dowager Kalakua, widow of King Kamehameha I, boarded the Thaddeus with a bolt of white cloth. She asked the missionary women to fashion it into a fine dress.

The wives sat in a sewing circle on the deck of the ship and finished the assignment. When Kalakua left the Thaddeus, she wore her new dress, a lace cap decorated with four roses, and a lace half neckerchief, gifts of the missionary women.

Kamehameha II was 30 miles south in Kailua and the Thaddeus with Kalanimoku and his entourage set sail.

Asa Thurston and Hiram Bingham came ashore in Kailua and met with Liholiho in his grass hale. They exchanged gifts and a meal. They requested permission to settle in Hawaii, but he did not reply.

English adviser of the king, John Young, suggested a compromise: a trial period of a year. After four days’ consultation, Kamehameha II agreed. Could they also establish a mission in Honolulu? Four days later the king said yes.

The Thurstons and the Holmans debarked to set up their mission in Kailua, with two of the Hawaiian translators.

A thatched hale with a floor of mats was given to the two couples. A large chest served for a dining table, small boxes for chairs and trunks for settees.

Three days after landing, the king gave them a large circular table of Chinese workmanship, and each day the king’s servants arrived with platters of fish, taro and sweet potatoes.

The others continued to Honolulu. Oahu Gov. Boki gave the Honolulu missionaries a building site on a treeless plain half a mile east of Honolulu, where they found it necessary to obtain water and firewood from a distance of several miles. At the time, Honolulu was a town of under 4,000 persons.

They built the first Western-style home on the site with materials brought from Boston.

High chiefs requested the Western women make them shirts, dresses and suits. From these early beginnings the design of the holoku evolved.

Missionaries Whitney and Ruggles traveled to Kauai with Prince George, whom Kaumualii had given up as lost. He begged the missionaries to stay and teach him and his queen to read.

They stayed eight weeks, but returned for good in July with their wives to start a mission in Waimea.

The missionaries learned the Hawaiian language quickly and turned it into a written form within two years. Soon most of the adults in the islands attended makeshift schools with books reproduced on the new printing press. Within two decades, historian Ralph Kuykendall estimates, 100 million pages had been printed in the Hawaiian language. This made Hawaii one of the most literate nations in the world.

The current Honolulu church building was erected in 1842, replacing a series of large thatched structures. It was constructed with over 14,000 coral blocks that were cut from the reef at low tide and moved to the site.

Divers dived 20-30 feet below sea level to chisel out the slabs, weighing about 1,000 pounds each, with hand tools.

The missionaries called it the king’s chapel, or the native chapel and later the stone church. Not until 1863, when it came under the pastoral care of Henry H. Parker, a mission son, did it become known, officially and generally, as Kawaiaha‘o.

By 1850 succeeding voyages brought over 140 missionaries to the kingdom. They fulfilled the charge that was read to the pioneer company before they sailed from Boston aboard the Thaddeus:

“You are to open your hearts wide and set your marks high. You are to aim at nothing short of covering these islands with fruitful fields, pleasant dwellings, schools and churches, and of raising up the whole people to an elevated state of Christian civilization.

“You are to obtain an adequate knowledge of the language of the people; to make them acquainted with letters; and to introduce the arts and institutions and usages of civilized life and society.”

Bob Sigall is the author of the five “The Companies We Keep” books. Email him at Sigall@Yahoo.com.