Even baby fish are eating plastics, Hawaii study finds

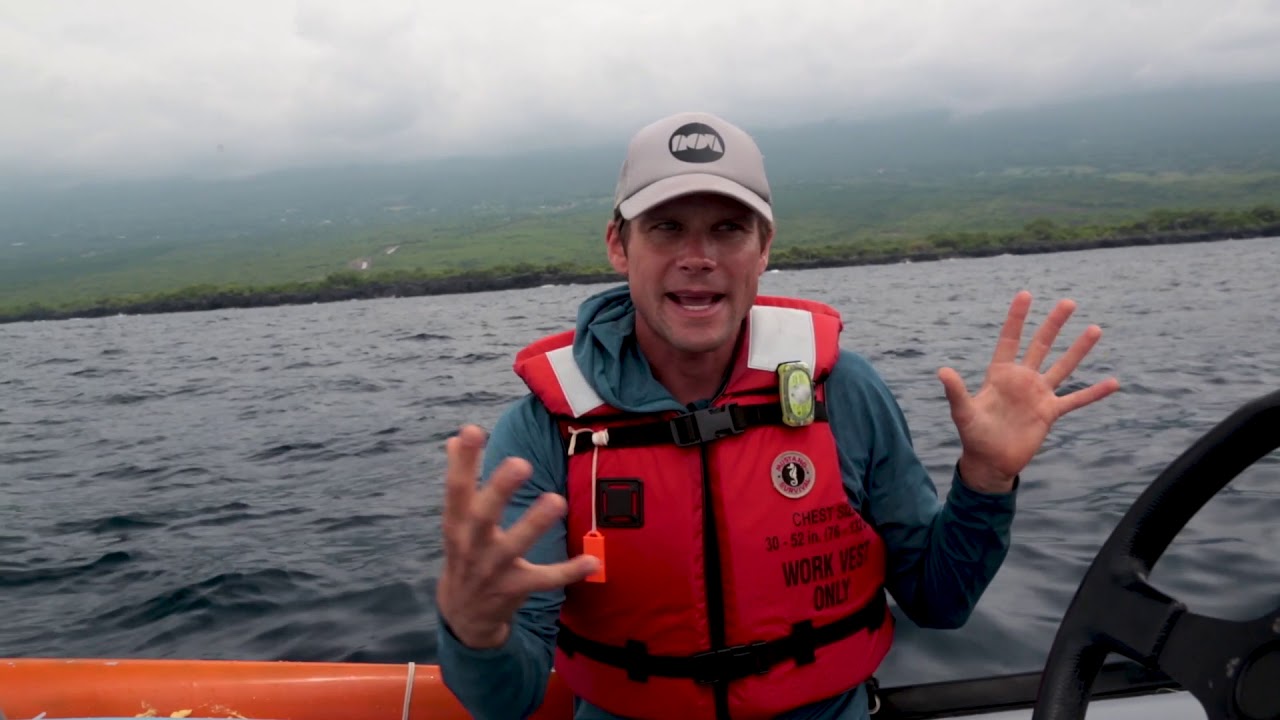

COURTESY NOAA

A Hawaii-based study found that both young coral reef fish and open-ocean species are consuming plastic as early as days after they are spawned.

Recent evidence has shown that adult fish are eating plastics in the ocean and suffering from perils such as malnutrition and toxicant buildup.

Now, for the first time, a study conducted in Hawaii shows baby fish are ingesting tiny plastics, too.

The research Opens in a new tab, published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that both young coral reef fish and open-ocean species are consuming plastic as early as days after they are spawned.

Working in the waters off West Hawaii, an international team of researchers focused on surface slicks — naturally occurring ribbons of smooth water at the ocean surface that are formed when underwater waves converge near coastlines, according to a NOAA news release. These biologically rich ribbons of water aren’t always visible to the eye but are commonly seen, especially if wind conditions are right.

Found in coastal waters around the world, the surface slicks accumulate high concentrations of plankton, a key food source that lures larval fish in huge numbers. These watery nurseries harbor an impressive variety of species from a range of habitats, ranging from the deep ocean waters to shallow-water reefs.

But the team, led by scientists at NOAA’s Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center in Honolulu, also discovered that the same forces that aggregate the prey for the tiny fish also bring floating plastics — lots of it.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

“We were shocked to find such high concentrations of microscopic plastics just off the island,” said co-lead author Jonathan Whitney, a marine ecologist with the University of Hawaii and NOAA’s Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research.

The researchers used fine-mesh nets to survey the surface slicks from Puako to Milolii, all within four miles of shore, between 2016 to 2018.

The concentration of plastics in these surface slicks were generally 12 times higher than what was found recently in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, according to NOAA. Plastics were found to be 126 times more dense in surface slicks than in surface water just a few hundred yards away. Additionally, there were seven times more plastics than larval fish.

The vast majority of the plastics were very small, less than 1 millimeter in size, or smaller than grain of ordinary table salt.

A microscope revealed tens of thousands of tiny pieces that couldn’t be seen while the researchers were on the water.

“It’s these tiny pieces that are being eaten by baby fish. It’s these tiny pieces that we can’t even see with our naked eyes that are the problem here,” Whitney said.

More than 600 larval fish were dissected and 48 of them were found to have ingested plastic particles, the researchers said. Plastics were found in the stomachs of commercially fished species such as swordfish and mahi mahi and in coral reef species like triggerfish. They were also found in flying fish, which are eaten by tuna and Hawaiian seabirds.

Jamison Gove, a research oceanographer for NOAA in Honolulu and co-lead of the study, said the study started out as an exploration of the surface slick habitat.

“We hadn’t anticipated how much plastics we would find. Once we started sampling and finding a lot of plastics, there was no way to ignore them,” Gove said. “The fact that larval fish are surrounded by and ingesting non-nutritious plastics, at their most vulnerable life stage, is certainly cause for alarm.”

It’s not clear what health effects plastic ingestion has on larval fish, but it’s probably not good and may even lead to eventual death, the researchers said. Plastic has already been shown to cause gut blockage, malnutrition and toxicant accumulation in adult fish.

As part of the study, satellites were used to measure the size and distribution of the surface slicks along the coast of West Hawaii. The study indicated that that surface slicks comprise less than 10% of ocean surface habitat but are estimated to contain 42.3% of all surface-dwelling larval fish and 91.8% of all floating plastics.

Biodiversity and fisheries production are threatened by a range of man-made stressors such as climate change, habitat loss and overfishing.

“Our research suggests we can likely now add plastic ingestion by larval fish to that list of threats,” Gove said.

There are some who criticize the spotlight given to plastic pollution, saying it takes away from efforts to deal more severe threats to global fisheries.

While Whitney agreed there are bigger problems, plastic pollution is still worthy of attention.

“We need to know the full scope of our impact on the marine environment so that we can make changes that will reduce the stress to already severely threatened marine life,” he said.

As the Honolulu City Council considers a bill to ban plastics affecting food vendors and other businesses, both scientists said they support efforts to reduce the amount of plastics that wind up in the ocean.

“Plastics have an important place in society, but it doesn’t make sense to manufacture something that will last for a hundred years but used only for minutes at the most,” Gove said.

And while many point out that most of the plastic in our ocean originates from distant sources, Hawaii should do its part.

“No amount of plastic is acceptable going into the ocean. Even a nominal amount is too much,” he said.