If you think the opposition to the Kahuku wind farm started last week when scores of protesters were arrested for trying to block construction of the planned project, think again.

Kent Fonoimoana said the community has been battling the proposed wind farm for more than a decade.

“They’re finally saying enough is enough,” said the former president of the Kahuku Community Association.

Fonoimoana said he and lots of others in Kahuku have challenged the wind turbine project at every turn, attending dozens of community meetings over the years, speaking at hearings, pleading with politicians and government officials, holding petition drives, distributing flyers and marching in peaceful protest.

Despite their efforts, AES Corp., the contractor for the wind farm, won the green light to proceed and is looking to build eight 568-foot wind turbines on the slopes of Kahuku.

There are already 12 shorter turbines in the rural North Shore community of 2,300.

Fonoimoana was already familiar with the low- frequency whirring of wind turbines from the existing farm when in 2008 he noticed heavy equipment working above his house. He climbed up the hill and — after being informed about what was going on — told the crews they were in the wrong spot, that the wind farm was on a different ridge. He was told, no, this is a new project.

He was dumbfounded because he had never heard about it, and apparently, few of his neighbors had as well.

The incident prompted Fonoimoana to run for the Kahuku Community Association board, and he won on the strength of his opposition to the proposed wind farm. And the few board members who supported the project were eventually voted off the board, he said.

A company representative, he said, told the board that if they really didn’t want the wind farm, it wouldn’t be built. When the board told him they didn’t want it, however, the project was sold to a different company, which eventually was sold to AES Corp.

With Fonoimoana at the lead, the association challenged the project at the Public Utilities Commission, the state Board of Land and Natural Resources, the City and County of Honolulu and at project open houses and informational meetings.

Fonoimoana said the goal wasn’t necessarily to kill the project, but to move it farther from people’s homes. The sound of wind turbines, he said, disrupts sleep and concentration. It also affects property values.

Former attorney James Wright said he filed the paperwork for the association’s BLNR contested case hearing against the proposal in 2016.

“I met with a number of individuals seeking financial and legal support,” Wright said. “It was clear the unhappiness was significant. They were demoralized and intimidated at the time. And while they did fight the project, their groundswell has only come now because people didn’t feel it was possible to be heard.”

Fonoimoana said he’s not surprised by what is happening now, given what happened on Mauna Kea. The frustration of 10 years of futile opposition is finally spilling over into action.

“They’re fed up. They’ve had it,” he said. “It’s the failure of our political leaders to protect its citizens against the big-moneyed interests.

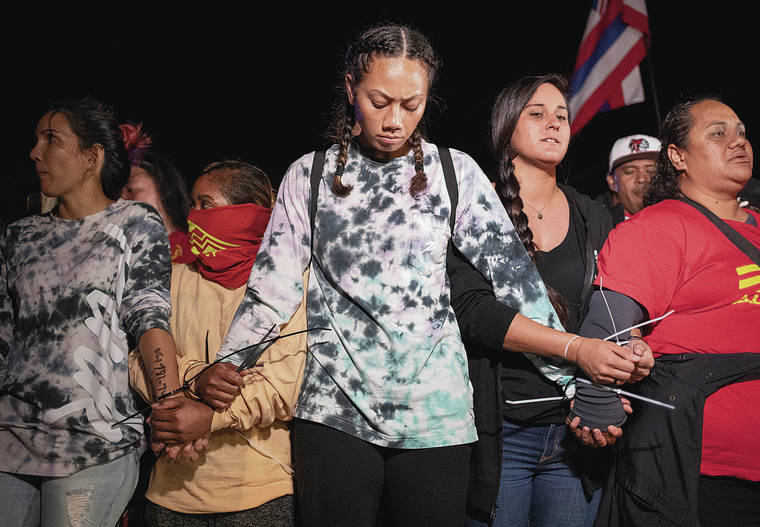

“I just wish if a community doesn’t want something, they should at least have a hand on the steering wheel and not be thrown in the trunk — bound and gagged.”