In July I wrote about my North Shore encounter with an octopus. After surprising the creature sitting out in the open, the octopus spewed its defensive ink, giving me only a glimpse of the animal before it disappeared in a swirl of black water.

This month in waters off Kailua, I saw another octopus, only this time it put on the show of a lifetime. The octopus was fighting for its life with a moray eel.

While snorkeling back from Lanikai’s outer reef, a long swim I sometimes make when the water is calm, the ocean floor suddenly rose up ahead of me in a tornado of sand. All I could see was the tail end of a yellowmargin moray eel whipping back and forth. A moment later the eel shot out from the sand cloud and dived under a coral head.

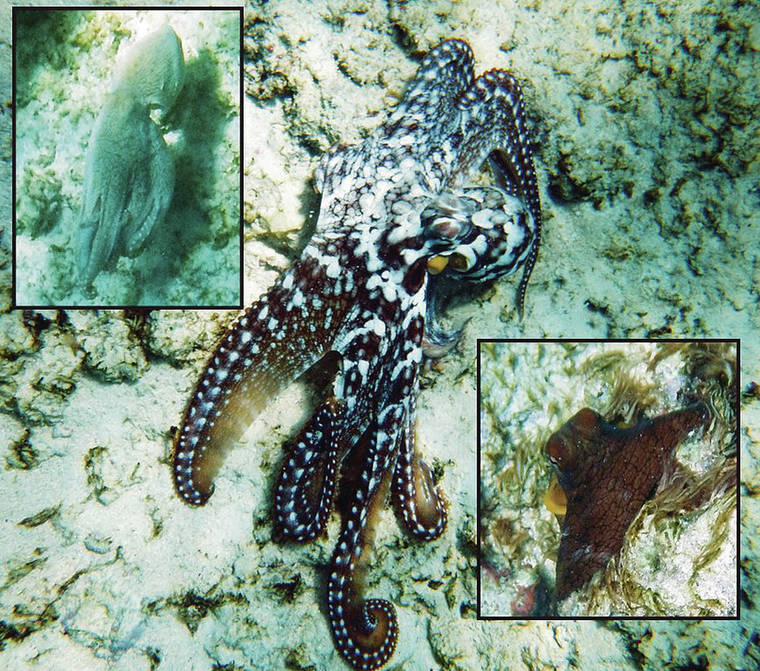

On the opposite side of the swirl, an octopus burst into the open, stopping just below me. As I raised my camera, the octopus slunk toward the shelter of a rock. Watching that animal change colors and shapes as it moved along was like looking through a kaleidoscope.

Octopuses, as well as their squid and cuttlefish cousins, can change color in a heartbeat, using cells called chromatophores that lie just beneath the surface of the skin. Each cell contains a stretchy bag full of a color, either black, brown, orange, red or yellow.

The animal’s nerves and muscles control the color bags, expanding to show the pigment inside or shrinking until the color is absent. Various combinations of colors help the creature match its surroundings to hide from predators or sneak up on prey. Other times, the color combos allow the animal to stand out to communicate with members of its own species.

Other octopus skin cells are reflective. Arranged in stacks of plates, the resulting colors are iridescent greens, blues, silvers and golds. Still other skin cells act like mirrors, reflecting the surrounding environment.

As if this coloring isn’t astonishing enough, octopuses can also change the texture of their skin to match algae, coral, rocks or sand. Skin surfaces range from smooth to small bumps to flappy projections.

Octopus is one of moray eels’ favorite meals. If a small eel ventures too close, however, an octopus might grab it with its powerful suckers and turn the tables, the prey becoming the predator. I suspect that’s what was happening when the smallish eel I saw made a run for it.

About my July column on octopuses, Betty, a Waialua reader, emailed, “Years ago I married a ‘local’ guy and learned to get rid of the ink from the ‘squid’ he caught … more recently I have found it a delight to eat! Your column has changed all of that: No more de-inking and no more eating, ever! They are (like most creatures) amazing.”

I too stopped eating octopus after I learned how intelligent and versatile they are. Getting to witness the great escape of that octopus made me feel happy all day.

To reach Susan Scott, go to susanscott.net and click on “Contact” at the top of her home page.