HILO >> The fast-moving events that unfolded last week show the Thirty Meter Telescope protests cannot be dismissed as a bump in the road. Increasingly, they seem to foretell a longer struggle.

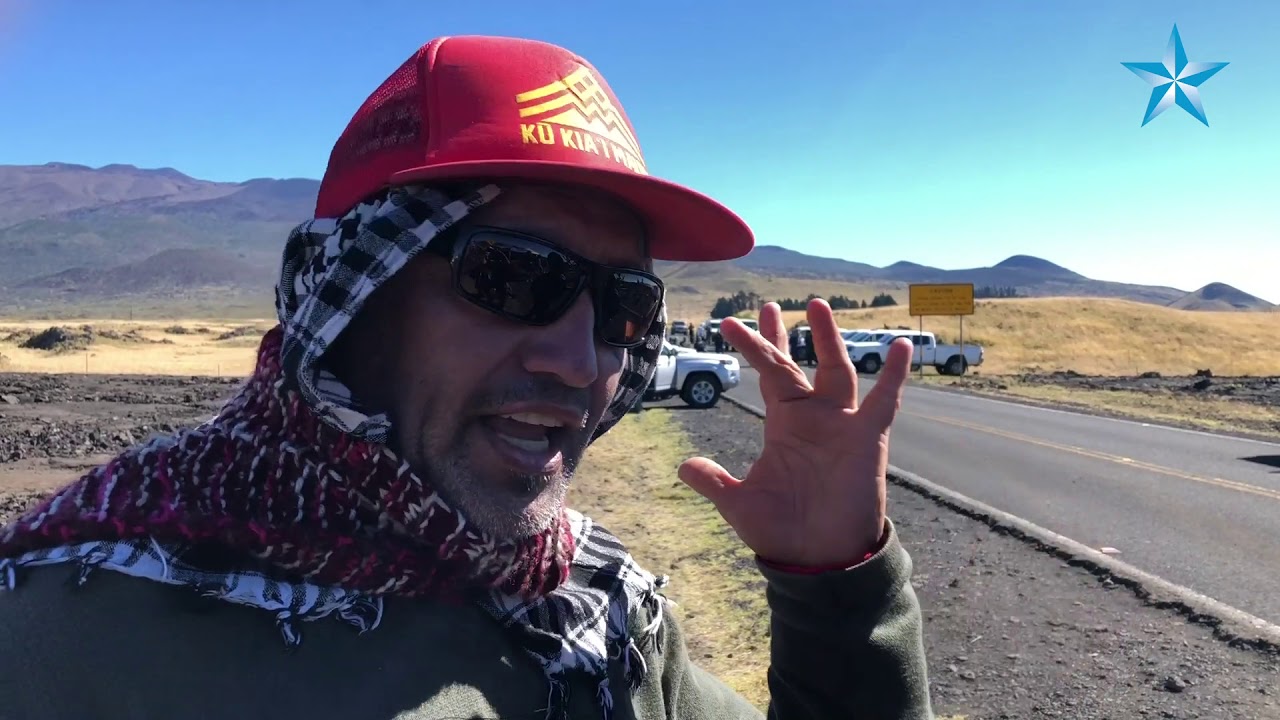

The self-styled “protectors” trying to block construction on Mauna Kea — they eschew the label “protesters” — have demonstrated organization, discipline, communication and a sophisticated understanding of modern-day nonviolent protest strategy and tactics.

They also have a powerful unifying symbol as their emotional rally point, a mountain that encapsulates long-standing Native Hawaiian grievances. Opponents of the $1.4 billion TMT project condemn it as a desecration of a mountain that some Hawaiians consider sacred.

There seems to be a pervasive sense among the protesters on the mountain that the community around them is uninterested in the deeper meanings of traditional Hawaiian culture and religious beliefs, and also an infuriating sense that nobody much cares what they think.

“This is more than just a mountain,” said Tate Keliihoomalu, 20, who jumped in her car Wednesday to join protesters in about 50 vehicles that slowed and then briefly stopped traffic on the H-1 freeway on Oahu.

Heading on to the Daniel K. Inouye International Airport, the group slowly circled the main concourse and stalled traffic, waving and calling to tourists as state sheriff’s deputies looked on. Keliihoomalu, who lives on Hawaiian homelands on Oahu, then bought a last-minute plane ticket to join the protesters on Mauna Kea Wednesday night.

“You have to protect what is yours, you know? And I think for so long we’ve just been forgotten, brushed off, and been made promises that are never kept,” she said. “Mauna Kea represents so much more as a lahui (nation) than anything else, and if we are to give this up, everything else is going to compound after that.”

Well-planned protests

While the 2015 protests on the summit of Mauna Kea seemed largely spontaneous, there is a sense this latest resistance is a long-awaited showdown for a community of people who feel disenfranchised, and each step of the protests this year seems well planned.

State officials estimated the crowd Tuesday to be 200 protesters, but when the activists felt the need for more troops, they used social media and other communication networks to summon reinforcements.

The next day the number of activists at the isolated mountain protest site surged to 1,000 by the state’s count, ranking it among the largest demonstrations seen in Hawaii in recent decades. There are very few other political organizations in Hawaii — if any — that could have swelled their ranks to that degree on such short notice.

Whatever he intended, Gov. David Ige acknowledged that feat when he issued his emergency proclamation Wednesday. The document can easily be read as an alarmed response to the anti-TMT movement’s ground game.

Undisclosed numbers of Honolulu police and state sheriffs were sent to Hawaii island, where they were joined by a contingent of Maui police officers and enforcement officers from the state Department of Land and Natural Resources. Hawaii County police were trained to prepare for this day and Hawaii National Guardsmen were mobilized.

Yet Ige’s declaration explicitly admitted that wasn’t enough, even though it was the state and TMT that decided when the project would move forward. According to the proclamation, the protests appear “to exceed the ability of law enforcement and first responders to maintain order.”

Likewise, the decision by telescope managers on the Mauna Kea summit to suspend operations Tuesday was acknowledgement of the power of the protest. Representatives of the 13 observatories say the activists did nothing to threaten or harass their workers, but management was concerned there was not “consistent and safe access” to the summit for staff.

The observatories remain shut down today, and suddenly it seems that all that has been built on Mauna Kea may be at stake, including some of the most sophisticated astronomy facilities in the world.

The frustration is palpable. Thirty Meter Telescope Executive Director Ed Stone issued a statement Friday reminding the public that “TMT has been very patient.”

The project is being developed by partners that include the California Institute of Technology, the National Institutes of Natural Sciences of Japan, the National Astronomical Observatories of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Department of Science and Technology of India. The permitting process including legal challenges took a decade.

“We worked very long and very hard to comply with all laws and regulations. We’ve also worked long and hard with the community and to develop understanding and respect for the culture,” Stone said in his statement. “We are and have been prepared to access the site, but our legal rights to access have been blocked. We don’t have the power to clear the blockade. We need to depend on law enforcement to do that. It’s a very difficult and urgent situation for us.”

Ige expressed his own frustrations at a press conference Friday, observing negotiations with protest leaders have been complicated in part because they don’t all agree on what they want from the state.

“I think that we’ve heard a wide range of issues, sovereignty to the Thirty Meter Telescope, to some of the inadequacies of the criminal justice system, and others, so certainly there is a wide range of issues raised as we have conversations,” he said.

Throughout it all, the demonstrators have employed nonviolent protest tactics called “kapu aloha” that are firmly grounded in Hawaiian values.

They positioned kupuna, or Hawaiian elders, in rows of folding chairs across Mauna Kea Access Road, blocking any attempt to send construction equipment to the summit to begin work on TMT. Arrangements were made with police for a series of gentle arrests of the kupuna who were willing, with great emphasis placed on traditional Hawaiian respect for the elders.

With the media crowding around and eager to record every moment, one kupuna after another surrendered to police in a meticulous process that lasted hours. Some would-be arrestees called out to law enforcement officers they knew, and some were related to the officers who stood over them, according to a state spokesman. The kupuna took water and bathroom breaks. Supporters hovered and passed around fruit and other snacks. An ukulele and singing supporters serenaded the kupuna. And some of the arrestees made powerful public statements.

“No pilau our land, this is pilau (foul or rotten), all that,” said “Auntie Tootsie” Peleiholani of Kalapana before she was arrested. “Haoles don’t know how to respect. Hawaiians, we know how. This is kapu aloha. You don’t see the kids throwing bombs and rocks at anybody, you don’t see them yelling at any. This is how, on our sacred land, we conduct ourselves according to how kupunas had taught us.

“Love ke akua (God) and love all you folks, but this is our aina. We is the rocks, we come from these rocks, we eat from these rocks, and we go back to these rocks. That’s a fact, from day one, for centuries.”

Three hours after the arrests began, it was clear each chair vacated by someone who was arrested would be quickly filled by another activist, and each recorded arrest created its own powerful online images and narrative.

This continued for nearly four hours until 34 people were arrested and hauled off in vans. The process finally ended for the day when additional police with riot gear entered the area, prompting the crowd to surge, chant and form up in ranks to bar law enforcement from reaching the kupuna.

Still respectful

Yet even during the heat of that confrontation Wednesday afternoon, the protesters were “absolutely respectful,” according to a state spokesman.

Documenting every moment of the protests is a sophisticated public relations operation. Immediately after the opening days of the protests, activists released professionally crafted videos set to music documenting some of the most emotional moments. Those videos and the deluge of other online protest images are vivid recruiting tools.

With hundreds of protesters’ cars parked along the Daniel K. Inouye Highway each day, it is also clear the movement is benefiting from a more publicly accessible protest site. Anti-TMT protests in 2015 were largely out of public view near the summit, but this time thousands of motorists honk as they drive by the protests each day on the busy commuter route between Hilo and Kona.

To people upset that the protests are slowing or stopping traffic on the highway, the activists retort that it was the state that planted the epicenter of the conflict at the intersection of the Mauna Kea Access Road and the highway.

“They forced us down to this highway. They forced us down to a 60-mile-an-hour speed limit. They forced into Puu Huluhulu,” protest leader Kahookahi Kanuha told law enforcement officers last week. “We could have been up there, out of the way of everybody like we were last time, but they don’t want us there. They forced us into it; it’s the only choice we have.

“It’s this or go home and watch it on wide screen. That ain’t happening.”