Lt. Gov. Josh Green targets homelessness

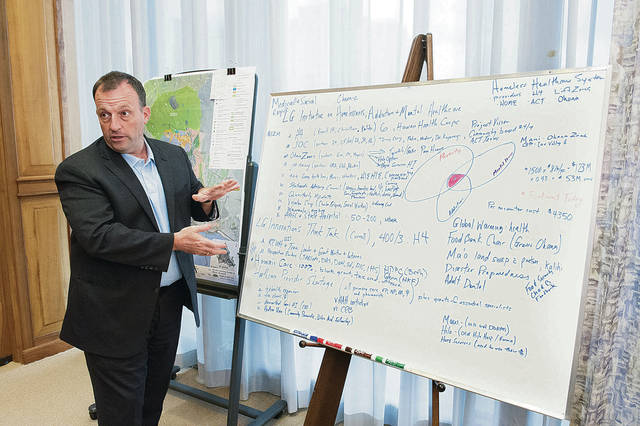

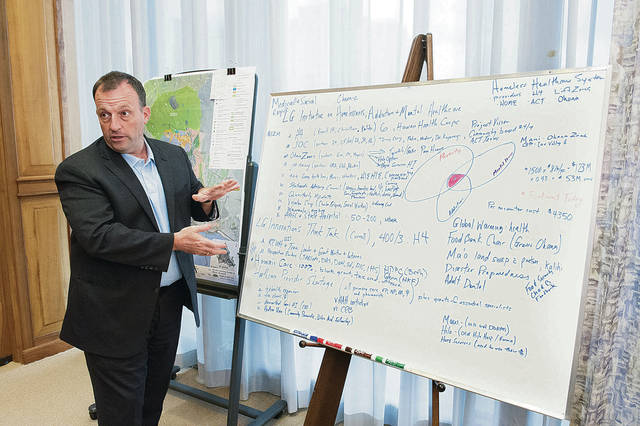

CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARADVERTISER.COM

Lt. Gov. Josh Green on Thursday discussed the projects he is planning to combat homelessness.

Lt. Gov. Josh Green estimates that two months into his new job, he spends 70 percent of his time focused on finding big and small ways to get more homeless people off the street.

His calendar is filled with meetings with diverse interest groups — from the American Civil Liberties Union of Hawaii, Honolulu police and the plumbers union to the Hawaii Restaurant Association — which Green says all have a stake in reducing homelessness across the islands, albeit from different perspectives.

Even before his election as lieutenant governor, Green, 49, as a Big Island emergency room doctor and as a state senator who represented Naalehu and Kailua- Kona, had a dual perspective on Hawaii’s homeless problem.

Now joining Gov. David Ige for Ige’s second term, Green told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser on Thursday that he is determined to do more — especially with this week’s news that the number of homeless people living “unsheltered” on Oahu jumped 12 percent in January, despite an overall homeless decrease of 4 percent on Oahu.

“When we see a surge of unsheltered homeless, it’s a massive problem,” Green said in his office at the state Capitol. “That’s what people see. That’s what the unsheltered homeless are experiencing. They’re suffering. So we have to have a lot of solutions all at once.”

Green is using many of his professional and personal contacts to search for ideas, including an uncle on the mainland who once worked as corporation counsel for the National Restaurant Association.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

Locally, with a December unemployment rate of 2.6 percent, Green said he learned that local restaurant owners would love to hire capable homeless people.

At the same time, he’s been meeting with ACLU of Hawaii officials who have often objected to the way that the city conducts its homeless sweeps.

“Whenever possible, dialogue is the best way forward, which is why we appreciated being invited to talks with the lieutenant governor,” ACLU Executive Director Joshua Wisch said in a statement to the Star-Advertiser. “We look forward to continuing these discussions with the state and city, especially when we can use those opportunities to help government agencies and officials avoid strategies that would violate the Constitution in the first place. We will always oppose tactics that criminalize poverty or violate the civil rights of vulnerable populations, even as we will always support lawful efforts that offer people housing, health and dignity. Eliminating houselessness is a huge challenge, and we believe that the most effective way to tackle it is working together to find Hawaii- specific, constitutionally grounded solutions.”

Green and his staff keep track of homeless ideas on a whiteboard that includes big-picture concepts such as global warming along with individual names such as Twinkle Borge, leader of the entrenched homeless encampment of 270 people next to the Waianae Small Boat Harbor known as Pu‘uhonua o Waianae.

The biggest single section of the board is dedicated to a Venn diagram illustrating the intersection of three issues that plague the homeless: poverty, mental illness and addiction.

It’s the people in that intersection — marked with a pink marker on Green’s whiteboard — who he says worry him the most.

“We start from the premise that we know that the high incidence of addiction and mental illness is driving the intransigent chronically homeless condition,” Green said.

Before becoming lieutenant governor, he often went out to the streets to treat homeless people. And in January, medical bag in tow, Green picked up drug needles around the Hawaii Children’s Discovery Center as homeless people moved out and into Mauka Kakaako Gateway Park.

The whiteboard in his office also lists several projects that Green said he believes Hawaii could see big progress on this year, including:

>> Passage of SB 1124, which he said would make it easier to treat homeless people with the Invega drug, which has proved successful in treating mental illness.

The Institute for Human Services can easily identify 40 people by name on Oahu who could benefit from Invega, Green said. But he believes the numbers are much larger.

“Statewide there’s probably 300 people who live in a very dark place and are chronically homeless,” he said. “If a person is already speaking to me in tongues as though they think they’re a Comanche Indian and have a degree from Harvard in medicine and law and works for the FBI and they’re schizophrenic, we can’t let them stay on the street until they’ve gotten some help. … That has to change.”

>> An agreement between the city and Board of Land and Natural Resources that will likely go before BLNR next month to allow the city to create tiny homes for about 150 homeless people currently living in and around Waimanalo Beach Park.

Instead, they would pay rent to live in tiny homes of about 150 square feet, sitting on trailers on 8 acres of state land.

“There would be a central kitchen, water and bathrooms,” Green said. “It’s not a tent. I agree with the city that there should not be tent cities. If I had my way, there would be no tents at all. This is permanent.”

If successful, Green would like to replicate the Waimanalo model four or five more times around Oahu and a couple of more times on each of the neighbor islands.

>> Creation of a second Joint Outreach Center, possibly in Kakaako, modeled after the original, which opened in Chinatown in April. So far, 1,200 people have received wound care and other medical treatments, including prescriptions for anti-depression medication.

“And some are getting put into permanent supportive housing because we have a ton of social workers there,” Green said.

Discussions continue, but Green hopes to see a second Joint Outreach Center open in Kakaako’s Next Step homeless shelter next to the University of Hawaii medical school.

>> Temporary “Lift Zones” or “Mobile Navigation Centers” run by Honolulu police and staffed by medical professionals that will operate in a specific location for no more than 90 days.

“They’re tents but they’re more solid, and there are going to have to be social services,” Green said. “We are in agreement that we don’t want to set up tent cities. Some people are going to call it a refuge; some people are going to call it Lift Zones. I’m calling it a solution in your region.”

While Green and the organizations and people he’s partnering with continue to push on several fronts, Green is simultaneously keeping an eye on the big picture as well as individual homeless people.

“We know for sure that people need help,” he said. “My role is to create a homeless health care system.”