Ted Tsukiyama: Nisei was Hawaii defender at time of mistrust of Japanese

STAR-ADVERTISER / 1997

Ted Tsukiyama paid tribute to the late Hawaii Supreme Court Judge Edwin Nakamura on Sept. 22, 1997, at Hosoi Garden Mortuary. Tsukiyama and Nakamura were childhood friends and 442nd Regimental Combat Team veterans. They served with the 522nd field artillery unit.

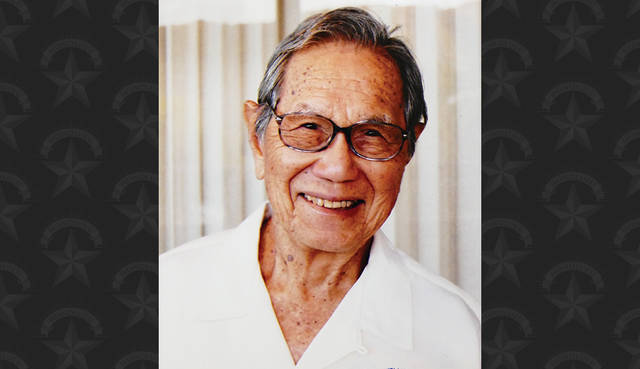

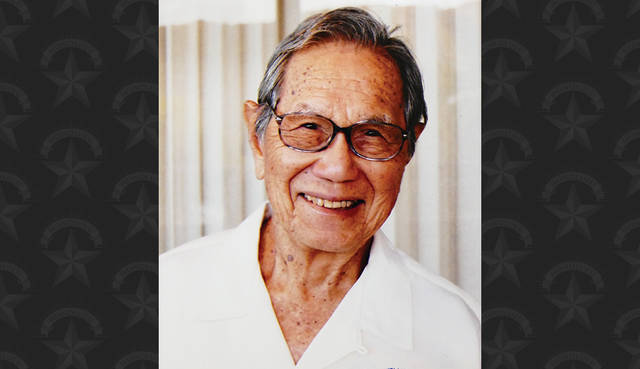

COURTESY PHOTO

Ted Tsukiyama, left, Junichi Buto and Ralph Yempuku in Bhamo, Burma, in 1945.

COURTESY PHOTO

“People were asking this kind of question: How are we going to act in the case where the enemy is people from the land of our ancestors? … We answered the call just like any other military personnel.”

Ted Tsukiyama

From a 1987 interview

Ted Tsukiyama lived a typical American life growing up on Oahu — until Dec. 7, 1941, and Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.

As a boy, Tsukiyama saved up his allowance to buy what became a prized baseball glove, even sleeping with it at night, his daughter Sandy said.

He used to get 5 cents every Saturday from his mother, and he and his friends would head to Kaimuki Theater to watch Westerns — “whooping and galloping back down the hill to 17th Avenue” afterward, she said.

The Pearl Harbor attack shocked Oahu and the nation, and became a turning point for another reason for Tsukiyama and other Japanese-Americans who experienced newfound mistrust in their own land.

“I’ve often said and felt that that was really the lowest point of my life,” Tsukiyama said in a 1987 oral interview.

But the onetime University of Hawaii student would prove his loyalty over and over as a member of the Hawaii Territorial Guard and the Varsity Victory Volunteers, 442nd Regimental Combat Team and Military Intelligence Service.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

Posted to northern Burma during the war, the lifelong Hawaii resident’s job was to listen in on Japanese Air Force radio transmissions behind enemy lines.

Tsukiyama, who was part of a nisei wave who used the GI Bill to obtain higher education and returned home to change the political landscape in Hawaii, died Wednesday of complications of a stroke. He was 98.

The labor lawyer and arbitrator, historian, writer and bonsai aficionado is also part of the rapidly fading wave of Japanese-Americans who belonged to the vaunted 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team whose “Go for Broke” patriotism and fighting spirit came at great cost to their own lives.

“Many people say this is the ending of the greatest generation,” Sandy Tsukiyama said. “They opened the door for things that many Asian-Americans take for granted today, and we can’t forget that.”

The World War II veteran spent decades as the historian for the 442nd and the MIS veterans clubs in Hawaii, said Mark Matsunaga, a board member with the MIS Veterans Club of Hawaii.

“He personally played a crucial role in going to the National Archives on the East Coast with some other volunteers and recovering documents and records that otherwise would have been lost to history,” Matsunaga said.

Tsukiyama “did more than almost anybody else to preserve the stories — the quintessential patriotic American stories — of what those AJA (Americans of Japanese ancestry) soldiers did during World War II,” Matsunaga said.

At the time of the Japanese attack on Oahu, Tsukiyama was a student and ROTC member at the University of Hawaii.

“After getting over the initial shock and anger that the Japanese would do a thing like this, the big concern that bothered all of us was we were on the spot,” Tsukiyama related in the 1987 interview. “People were asking this kind of question: How are we going to act in the case where the enemy is people from the land of our ancestors?”

There was no question as to which side Tsukiyama and other Hawaii nisei were on. That same morning, the ROTC cadets were issued rifles to be used in the defense of Hawaii.

“We answered the call just like any other military personnel,” he said.

The ROTC students were ordered to St. Louis Heights when rumors surfaced of Japanese paratroopers landing on the high ground.

That afternoon the cadets were commissioned into the Hawaii Territorial Guard and for six weeks guarded Oahu installations. It was then the War Department ordered the discharge of those of Japanese ancestry. The nisei had been classified as “4C” — enemy aliens.

That still didn’t deter Tsukiyama and others from seeking to serve their country.

About 160 former Hawaii Territorial Guard members at UH volunteered for non-armed duty with what became known as the Varsity Victory Volunteers, he said.

“The country needed every available man, whether it was with a gun or with a pick and shovel, so we volunteered as a labor battalion” building the defenses of Hawaii, Tsukiyama said.

That loyalty would eventually extend onto the battlefields of Italy and France where the Japanese- American 100th and 442nd became the most decorated units for their size and length of service in U.S. military history.