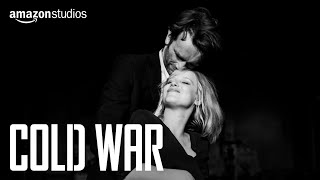

Review: Romance clashes with politics in ‘Cold War’

COURTESY AMAZON

Cold War smolders and even burns with the gorgeous, intoxicating atmosphere of star-crossed romance.

Giving the lie to its frigid title, “Cold War” smolders and even burns with the gorgeous, intoxicating atmosphere of star-crossed romance.

Passionate, tempestuous, haunting and assured, this latest from writer-director Pawel Pawlikowski explores, as did his Oscar-winning “Ida,” Poland’s recent past, resulting in a potent emotional story with political overtones that plays impeccably today.

Set between 1949 and 1964, at the height of the East-West political standoff that gives it its name, “Cold War” stars top Polish actors Tomasz Kot and the knockout Joanna Kulig as a tempestuous duo whose emotions are so large and so contradictory they could be characters in an opera.

Yet so assured is Pawlikowski’s direction, so convincing are the performances and so involving is Lukasz Zal’s gorgeous black and white cinematography (shot, as was “Ida,” in the old-school film academy screen ratio) that the entire story unfolds with a happening-right-in-front-of-us immediacy that is dazzling.

Set on both sides of the Iron Curtain, “Cold War” is a dramatization of the beyond-tumultuous personal history of the director’s mother and father. He’s even given the protagonists his parents’ first names, Wiktor and Zula.

Wiktor is an ethnomusicologist who in the beginning of the film is living in post-war Poland. With a fellow scholar Irena and Communist Party apparatchik Lech Kaczmarek (Borys Szyc) in tow, he is searching for the obscure, often cacophonous “music of the people.”

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with top news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

They stop at a former grand estate now transformed into a music academy, a place where the trio will be polishing melodies, “the music of your grandparents, the music of pain and humiliation,” and auditioning young performers for the dancing and singing folk ensemble troupe Mazurek.

“No more,” thunders Kaczmarek, who barely believes in the project, “will the talents of the people go to waste.”

Zula, played with incendiary charisma and an eye for the main chance, is a singer, played as an electrifying femme fatale by Kulig. She’s both ambitious and gifted, a kind of blond-braided Heidi with a come-hither look, and immediately kicks “Cold War” into a higher gear.

Zula maneuvers herself into the best possible position for inclusion. Not that any great subterfuge is necessary: Zula turns out to be a kind of Slavic It Girl, someone whose energy, talent and charisma are undeniable.

She and Wiktor also are unmistakably drawn to one another, with results both ecstatic and catastrophic. Not only do they both have volatile artistic temperaments, but Wiktor’s tortured aestheticism and Zula’s wary pragmatism are also bound to clash.

And that doesn’t take into account the directives and imperatives of Poland’s ruling Communist Party, determined to enforce not only where but also how people are allowed to live.

Party line politics first emerge after Mazurek’s successful Warsaw debut. Very nice, a government minister says, but what if in addition to genuine folk melodies, songs were added about the virtues of land reform and the genius of Stalin? No problem, says Kaczmarek and, already intoxicated with Zula, Wiktor goes along for the ride.

Part of the incentive for Wiktor getting more political is concert performances in Prague, Moscow, even Berlin, where in these pre-Wall days, simply walking across to the Western side is still possible. Wiktor is desperate to go; Zula, not surprisingly, is not so sure.

Music is obviously central to “Cold War.” Key songs are heard three different ways: primitive folk versions, uptempo Mazurek productions and jazzy Parisian ballads. It’s as exciting as it sounds.

“Cold War” succeeds because of its compelling portrait of a volatile relationship, an examination of what we do for love and what love won’t do for us.

“COLD WAR”

****

(R, 1:28)