Hawaii Ponzi schemer and professed secret agent dies at 76

STAR-ADVERTISER

Hawaii Ponzi schemer and professed secret agent Ronald Rewald duped about 400 investors of $22 million. He was 76 and died in California in December after living 23 years as a free man out of the limelight.

STAR-ADVERTISER

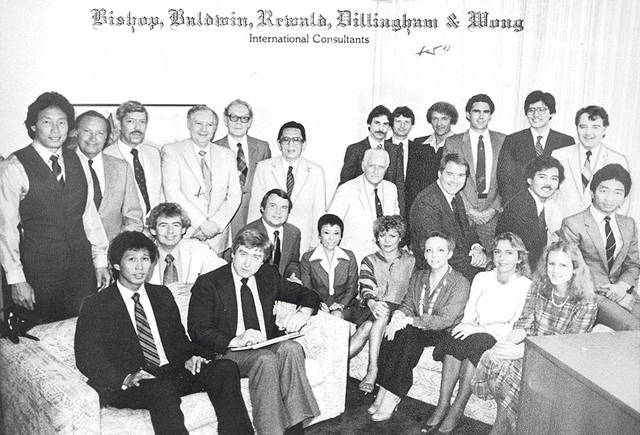

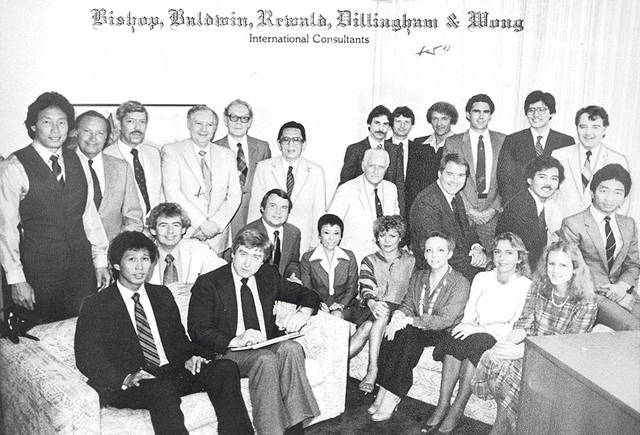

Ronald Rewald set up fraudulent investment company Bishop Baldwin Rewald Dillingham & Wong in 1978 using three names of kamaaina industrialists who had no connection to the firm. Wong (pictured at left in the front row) was Sunlin “Sunny” Wong, a local real estate broker who served as president.

STAR-ADVERTISER

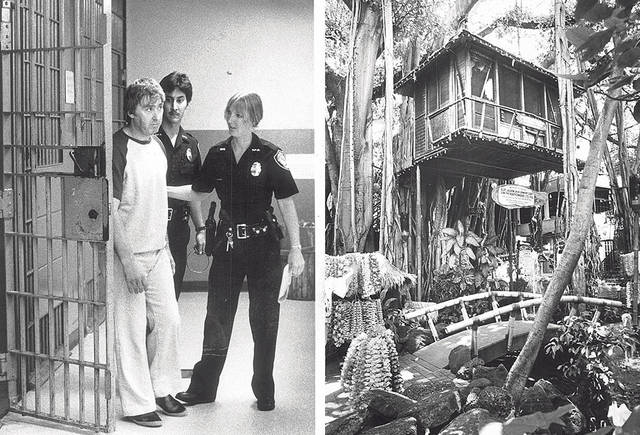

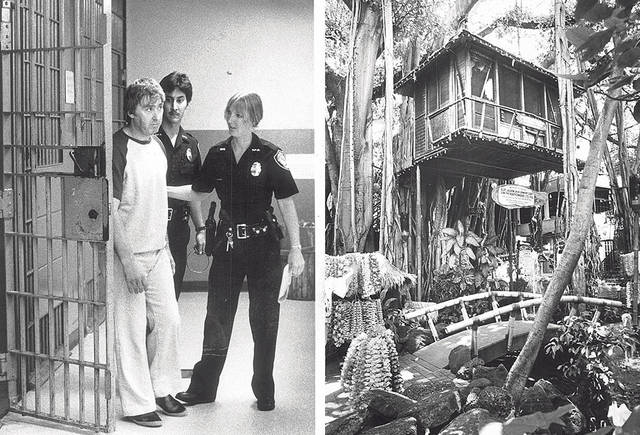

Ronald Rewald is shown at a police holding cell after a grand jury indictment in 1983. One of his fraudulent investment company’s “offices” was the treehouse at International Market Place in Waikiki pictured at right.

STAR-ADVERTISER

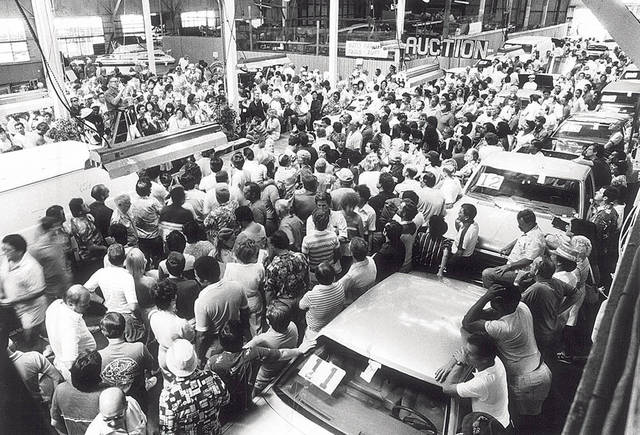

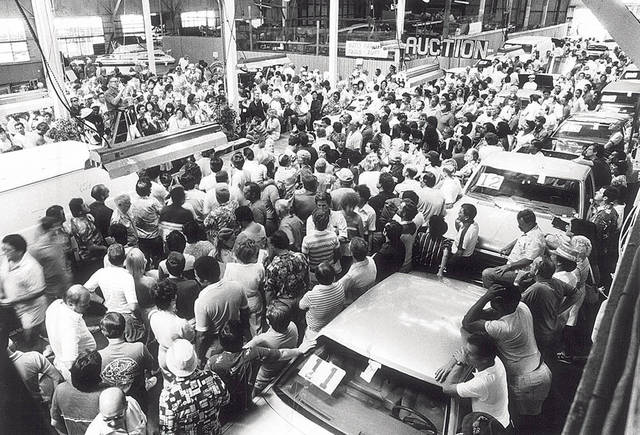

Ronald Rewald had his possessions auctioned at the Honolulu Flea Market in 1985. It fetched $185,000 for Rewald’s collection of 23 cars. Other items sold included a mobile dressing room Rewald bought from “Hawaii Five-0” star Jack Lord.

STAR-ADVERTISER

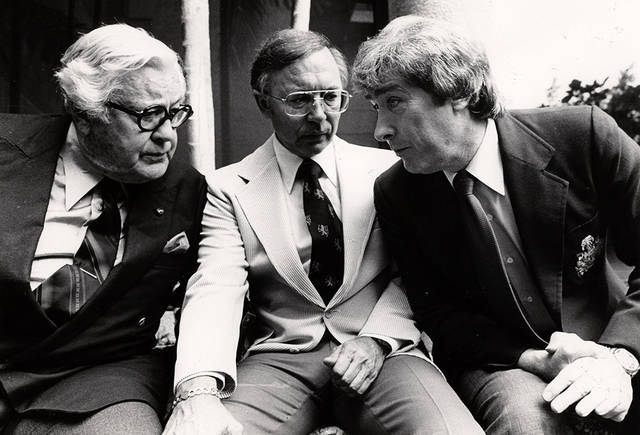

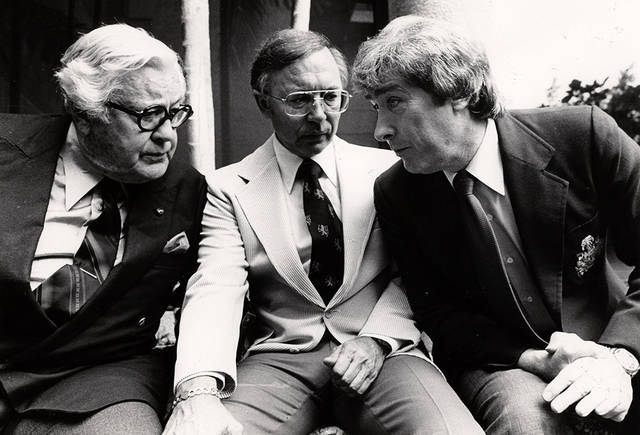

San Francisco lawyer Melvin Belli, left, talks to Ronald Rewald while Ted Frigard listens after a Bishop, Baldwin, Rewald, Dillingham & Wong creditors meeting. Belli represents Frigard and a group of creditors in their suit against the CIA, which Frigard claims was responsible for the collapse of Rewald’s company.

STAR-ADVERTISER

Ronald Rewald, center, is accompanied by his wife, Nancy, and his attorney, federal Public Defender Michael Levine, on the way to court for his trial on fraud charges.

STAR-ADVERTISER

Ronald Rewald talks to reporters outside court for his trial on fraud charges.

STAR-ADVERTISER

Some of Ronald Rewald’s cars that were sold. Rewald also owned Sports Hawaii stores and opened custom luxury car dealership Motorcars Hawaii.

STAR-ADVERTISER

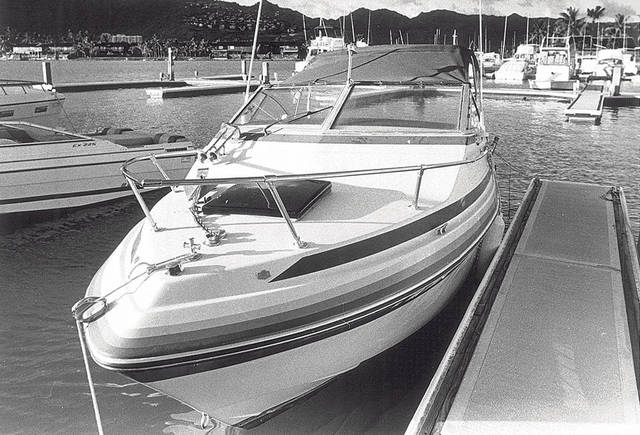

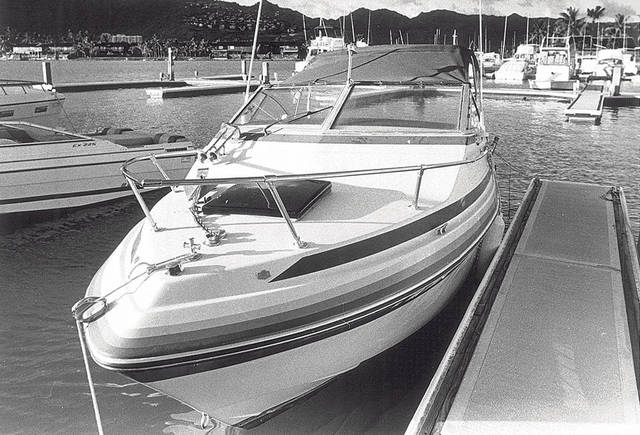

Ronald Rewald’s boat. He also acquired a North Shore ranch, a fleet of cars that included a Rolls Royce and the former limousine of Gov. George Ariyoshi, the Hawaii Polo Club and a downtown office featuring a waterfall.

STAR-ADVERTISER

Ronald Rewald’s $950,000 oceanfront home in Kuliouou.

Hawaii’s most notorious branded conman, a Wisconsin native who claimed to be a CIA agent but swindled money from hundreds of island residents and served barely 10 years of an 80-year prison sentence, has died.

Ronald Rewald was 76 and died in California in December after living 23 years as a free man out of the limelight.

That limelight was bright and ultimately scorching during the nine years Rewald lived in Hawaii in the 1970s and 1980s, a time during which he hobnobbed with celebrities, collected fancy cars, hosted royalty at polo matches and ran a purportedly venerable investment firm called Bishop Baldwin Rewald Dillingham & Wong where lofty financial gains were guaranteed.

Rewald was convicted in 1985 of 94 counts of fraud, tax evasion and perjury for running what a federal judge deemed a Ponzi scheme that sucked in $22 million from roughly 400 investors, including friends, widows and a blind man.

The scheme’s size was grand ($22 million would be about $55 million today) and produced a saga that attracted a national media frenzy, embarrassed the Central Intelligence Agency and publicized Rewald’s dealings with celebrities, politicians and the spy agency.

“It was massive publicity,” recalled former federal public defender Michael Levine, who helped represent Rewald at trial and had to get a security clearance to see classified evidence. “That was a very traumatic trial.”

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

Former mayor Peter Carlisle, who was a deputy city prosecutor involved in Rewald bail issues before trial, said Rewald created a scandal for the decades.

“He is the poster boy of despicably mind-numbing greed,” Carlisle said.

Living a lie

Rewald was born in Milwaukee, and accounts of his early adult life gleaned from court documents describe someone who was paid by the CIA to infiltrate student groups during college in the 1960s, made doubtful claims of being on three NFL football teams, stumbled in business and falsely boasted that he earned degrees from Marquette University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

In Wisconsin, Rewald headed a company that sold sporting goods to schools, College Athletic Inc. But he wound up in bankruptcy and admitted to a theft charge for illegal offers to sell franchises of his business. After that, Rewald formed investment advising firm CMI and moved to Hawaii in 1977.

By 1978 Rewald, who had five children, had a new company, Bishop Baldwin Rewald Dillingham & Wong, which used the last names of kamaaina industrialists and was advertised as having been in business 30 years with clients including White House administrations and Elvis Presley.

There was no Bishop, Baldwin or Dillingham involved. However, Wong was 27-year-old real estate broker Sunlin “Sunny” Wong, who agreed to be president of the firm through which a 36-year-old Rewald began soliciting investments supposedly insured up to $150,000 by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and guaranteed to produce 20 percent returns.

Rewald soon was living lavishly.

He acquired a $950,000 waterfront Kuliouou estate, a North Shore ranch, a fleet of cars that included a Rolls Royce and the former limousine of Gov. George Ariyoshi, the Hawaii Polo Club and a downtown office featuring a waterfall. Rewald also owned Sports Hawaii stores and opened custom luxury car dealership Motorcars Hawaii.

Bishop Baldwin claimed to have 157 employees in far-flung office locations including San Francisco, London, Stockholm, Paris, Hong Kong and New Zealand.

By 1983 the Internal Revenue Service, FDIC, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and state Department of Commerce and Consumer Affairs were looking into the company.

The truth catches up

Following subpoenas from DCCA and a TV news report raising questions about Bishop Baldwin in July 1983, Rewald was discovered in a room at the Sheraton Waikiki with a slashed forearm but alive.

A suicide note he left for his wife, Nancy, and quoted in a Honolulu Star-Bulletin story said: “I know how bad everything must look to all of you and everyone else. I want you to know I never did anything to hurt anyone. Someday I pray the truth will be known. I started out working for our country and was abandoned when others feared for their jobs. It never dawned on me that I would be left alone and unprotected.”

The story also quoted Rewald as saying to hotel security guards before an ambulance arrived: “I wish I were dead.”

Rewald claimed later in court documents that he set up Bishop Baldwin at the CIA’s behest and that the spy agency was supposed to repay investors their money that Rewald spent on himself to maintain his cover and on business operations related to missions. His CIA-given spy name, he claimed, was Winterdog.

CIA officials testified, according to a Star-Bulletin report, that dealings with Rewald were limited to him providing a business, phone and telex service available to agents needing “light cover.” Rewald’s CMI firm and two fictitious companies were approved for this even though a CIA security clearance official had advised against using Rewald over concern that his Wisconsin conviction might be “only the tip of the iceberg.”

The only financial deal between the CIA and Rewald was the agency reimbursing Rewald $2,900 for telephone and telex expenses, the agency testified.

Court records did show that Rewald passed the CIA information he gleaned from associates and foreign travel, including plans for a high-speed levitation train in Japan, an endeavor to search for American prisoners of war in Laos and discussions with an associate of the son of India’s prime minister concerning a desire to buy military equipment.

The crux of the case, however, was whether Rewald defrauded investors.

The trial lasted 11 weeks and involved 140 witnesses, including Wong, who accepted a two-year prison sentence in a plea agreement.

Rewald didn’t testify and complained that Judge Harold Fong wouldn’t let him introduce certain CIA-related material that the judge deemed irrelevant.

A jury found Rewald guilty in October 1985. Fong imposed an 80-year sentence, saying he didn’t know of a “more reprehensible set of circumstances” surrounding a “systematic plan,” according to Honolulu Advertiser and Star-Bulletin stories.

Fong also fined Rewald $352,000 and ordered him to pay restitution of possibly up to $13 million. It’s unclear whether any of that was paid.

Among his victims

Among Rewald’s victims were five CIA employees who were friends of Rewald and lost as much as $300,000, a neighbor who invested $805,394 and a Honolulu woman who invested an $82,000 insurance payment she received in connection with a skydiving plane crash that killed her husband and two sons.

Some investors, particularly early ones, received some or all of their money back. Government attorneys said Rewald paid out about $10 million in investment returns. Another $5.5 million went to running his businesses and $5.5 million for personal expenses including real estate, cars, boats and what prosecutors claimed was $270,000 paid to women for companionship and sex.

A bankruptcy trustee who collected and liquidated Rewald’s assets reported recovering $5.3 million, though $1.2 million of that got consumed by legal fees.

Rewald was eligible for parole after 10 years, but he left prison even before that despite unsuccessful appeals reaching the U.S. Supreme Court.

In June 1995 Rewald left Terminal Island Prison in California after claiming in a lawsuit that he wasn’t getting proper medical attention for a spine injury he suffered in 1988.

The injury, Rewald claimed, partially paralyzed his legs and made it necessary that he wear diapers because he had no bladder or bowel control.

Rewald in 2010 was working as the director of operations for Beverly Hills-based talent and literary agency APA. A company official confirmed Rewald’s death but deferred further comment to family members who did not respond to a request for information through APA.