Cartoonist Dick Adair remembered for dry sense of humor

STAR-ADVERTISER

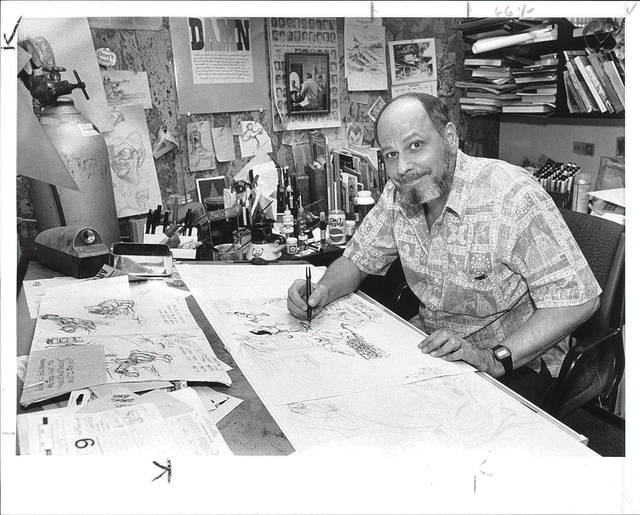

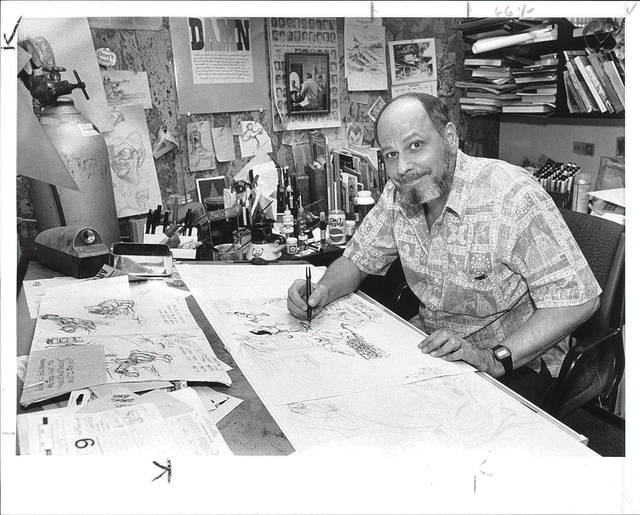

Honolulu Advertiser cartoonist Dick Adair works in his office at the Honolulu Advertiser.

STAR-ADVERTISER

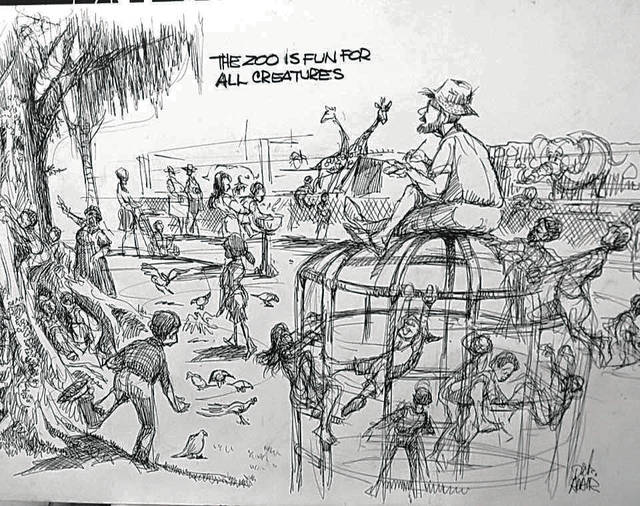

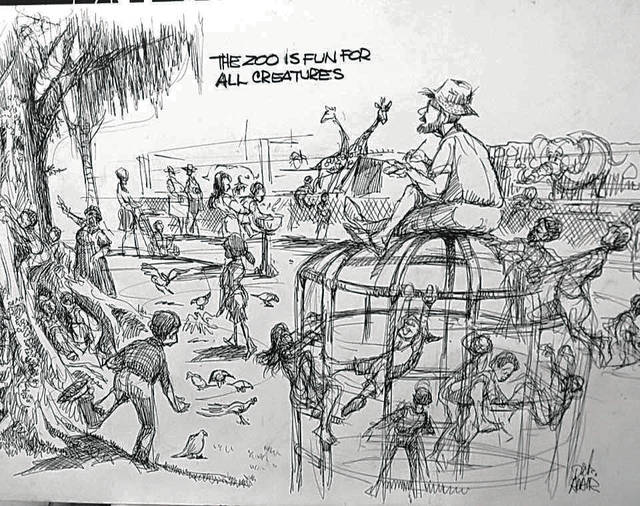

Above, art from Adair’s Facebook home page.

Dick Adair, an editorial cartoonist who amused and sometimes outraged Hawaii newspaper readers for more than three decades, died at his Hawaii Kai home Monday from cancer. He was 82.

Adair was best known to Hawaii residents as the longtime cartoonist for The Honolulu Advertiser, which hired him in 1981 and then let him go during staff cuts 27 years later. His cartoons continued to run until January in MidWeek, which is owned by Oahu Publications along with the Honolulu Star-Advertiser.

Adair was remembered by family and friends Tuesday mostly for his dry, acerbic humor and his ability to quickly draw on current events and news stories to make broader points about society. Politicians were among the most frequent targets of his penned commentary.

“He always put a twist on news stories and topics that made you think,” said Gerry Keir, who as Advertiser editor from 1989 to 1995 worked closely with Adair. “We were lucky to have him.”

A native of Chicago and lover of art, dance and theater, Adair held many jobs, especially in his younger years. At times he was a merchant seaman, dancer for a Mexican ballet company, theater actor, blimp pilot, Navy journalist and war correspondent for the military newspaper Stars and Stripes.

He married wife Margot in 1974 in Manila, and the couple moved to Hawaii five years later.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

“The thing I enjoyed about his company was his sense of humor and the way he looked at things differently,” Margot, 71, recalled of their 44 years as a married couple. “He was always an anchor for me. I tend to get very romantic and overly optimistic. He tended to be very realistic, so he was a good balance for me.”

Adair’s love for art showed even as cancer took a toll on his health.

Margot said Adair sketched up until January, even drawing on his bedsheets and the bedroom wall at their Hawaii Kai home. She gently scolded him for that, but “that’s how he was with his artwork. He would draw on anything that was in front of him,” she said.

Margot finally put her foot down late last year: She forbade him to draw on his bedroom curtains.

Jim Weander, 70, remembers meeting Adair at Roy’s in Hawaii Kai, one of the artist’s favorite eating spots. Adair frequently would bring the cartoon he drew for the Advertiser that day to show the regulars at the bar.

Weander said he and wife Susan became good friends with Adair and were impressed with his sophisticated insight and deep artistic ability — qualities that weren’t always obvious with his newspaper cartoons.

“We got to see the other side of him that was beyond the cartoons,” the Hawaii Kai resident said.

At times, Margot said, the bartender at Roy’s would give Adair a stack of napkins, and he would sketch on them and give the drawings to appreciative patrons.

Adair’s work often had an edge that didn’t sit well with some, especially those he took aim at.

When exiled Philippine leader Ferdinand Marcos lived in Hawaii in the late ’80s, Adair’s Marcos cartoons so angered the leader’s local supporters that they burned Adair in effigy.

When Adair aimed his sketched barbs at the late Mayor Frank Fasi, the fiesty politician sometimes would send a letter complaining to Adair. It would be “signed” by Fasi’s dog, Gino.

“He enjoyed poking fun at politicians,” Margot said, “but he also was very good friends with some. There was no animus.”

Manoa resident Jim Rumford, 69, an author and illustrator of children’s books, said he had many wonderful discussions with Adair about art. “The thing that amazed me was his breath of knowledge about all kinds of techniques of art and artists,” Rumford said. “He just didn’t limit himself to drawing pictures.”

Adair was the author of “Dick Adair’s Saigon: Sketches and Words From the Artist’s Journal” and two children’s books that he also illustrated.

In addition to his wife, Adair is survived by sons Richard of Seattle and Alexander of Honolulu, and grandchildren Gracey, Tatyana and River.

No services are scheduled. Adair donated his body to the University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine for science.